Brahmin

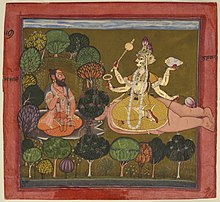

[1][2][3][4][5] The traditional occupation of Brahmins is that of priesthood (purohit, pandit, or pujari) at Hindu temples or at socio-religious ceremonies, and the performing of rite of passage rituals, such as solemnising a wedding with hymns and prayers.

[12] Modern scholars state that such usage of the term Brahmin in ancient texts does not imply a caste, but simply "masters" (experts), guardian, recluse, preacher or guide of any tradition.

He also states that "The absence of literary and material evidence, however, does not mean that Brahmanical culture did not exist at that time, but only that it had no elite patronage and was largely confined to rural folk, and therefore went unrecorded in history".

[22] Their role as priests and repository of sacred knowledge, as well as their importance in the practice of Vedic Shrauta rituals, grew during the Gupta Empire era and thereafter.

[22] However, the knowledge about actual history of Brahmins or other varnas of Hinduism in and after the first millennium is fragmentary and preliminary, with little that is from verifiable records or archaeological evidence, and much that is constructed from ahistorical Sanskrit works and fiction.

[24] The northern Pancha Gauda group comprises five Brahmin communities, as mentioned in the text, residing north of the Vindhya mountain range.

According to Kulkarni, the Grhya-sutras state that Yajna, Adhyayana (studying the vedas and teaching), dana pratigraha (accepting and giving gifts) are the "peculiar duties and privileges of brahmins".

[7][9] Donkin and other scholars state that Hoysala Empire records frequently mention Brahmin merchants who "carried on trade in horses, elephants and pearls" and transported goods throughout medieval India before the 14th-century.

The Pali Canon and other Buddhist texts such as the Jataka Tales also record the livelihood of Brahmins to have included being farmers, handicraft workers and artisans such as carpentry and architecture.

[40][44] Buddhist sources extensively attest, state Greg Bailey and Ian Mabbett, that Brahmins were "supporting themselves not by religious practice, but employment in all manner of secular occupations", in the classical period of India.

Under Golconda Sultanate Telugu Niyogi Brahmins served in many different roles such as accountants, ministers, in the revenue administration, and in the judicial service.

[47] During the days of Maratha Empire in the 17th and 18th century, the occupation of Marathi Brahmins ranged from being state administrators, being warriors to being de facto rulers as Peshwa.

[52] The East India Company also recruited sepoys (soldiers) from the Brahmin communities of Bihar and Awadh (in the present day Uttar Pradesh)[53] for the Bengal army.

Among Nepalese Hindus, for example, Niels Gutschow and Axel Michaels report the actual observed professions of Brahmins from 18th- to early 20th-century included being temple priests, ministers, merchants, farmers, potters, masons, carpenters, coppersmiths, stone workers, barbers, and gardeners, among others.

[57][58] The survey reported that the Brahmin families involved in agriculture as their primary occupation in modern times plough the land themselves, many supplementing their income by selling their labour services to other farmers.

[77] During the Konbaung dynasty, Buddhist kings relied on their court Brahmins to consecrate them to kingship in elaborate ceremonies, and to help resolve political questions.

[77] Hindu Dharmasastras, particularly Manusmriti written by the Prajapati Manu, states Anthony Reid,[78] were "greatly honored in Burma (Myanmar), Siam (Thailand), Cambodia and Java-Bali (Indonesia) as the defining documents of law and order, which kings were obliged to uphold.

[78][79][80] The mythical origins of Cambodia are credited to a Brahmin prince named Kaundinya, who arrived by sea, married a Naga princess living in the flooded lands.