Bremen Soviet Republic

Although not formally declared until 10 January 1919, the regime it represented presided in the industrial port city of Bremen from 14 November 1918 until its suppression on 4 February 1919 by army and irregular forces engaged by the provisional revolutionary government in Berlin.

The Soviet Republic was riven by disagreement over the nature of its mandate, the management of a developing financial and supply crisis, and the accommodation of national parliamentary elections.

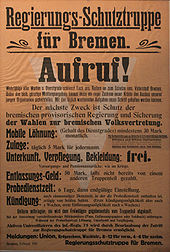

On 4 February 1919, a combination of regular army troops and irregular Freikorps occupied the city, breaking a disorganised resistance and putting an end to the Republic.

[2] In the wake of the deprivations and reverses of the Great War, the legitimacy of such oligarchic arrangements in the city-state's government collapsed, as did those of the imperial regime in Berlin.

A soldiers' council formed among locally stationed army units, and a delegation of sailors from Kiel sought their support in resisting the reimposition of military command.

After deliberations between the various delegations and political factions present, Adam Frasunkiewicz of the Independent Social Democrats (a left-wing anti-war splinter from SPD) announced that workers would meet with the soldiers in a city-wide council.

They formed an executive Action Committee of initially 15 members but extended to 21 to include representatives of the trade unions and the MSPD, who were seen to bring needed administrative expertise.

[6] In the council elections of 6 January, the MSPD sought to get around the restriction of the franchise to members of the three left parties by opening its ranks to large numbers of previously unaligned workers and civil servants.

[9] The USPD was internally divided over the relation between workplace delegation and parliamentary representation, but generally saw the councils as transitional institutions that would facilitate the socialisation of the economy.

In opposition to the MSPD, Henke went so far as to suggest that the prospect of a bourgeois parliamentary, as opposed to proletarian revolutionary, majority had been enhanced by the extension of the national franchise to women.

The Left Radicals then called a mass meeting on 22 November, which passed a resolution demanding the disarmament both of the middle-class and the Majority Social Democrats and their exclusion from the councils.

On the same day, however, the council of the Bremen garrison which, even in the absence of commissioned officers, represented a broad social cross-section, decided against the arming of a workers' militia (a "Red Guard").

Supporting the MSPD, they also prevented the USPD and IKD from seizing exclusive editorial control of the city's principal newspaper, the Bremer Bürger-Zeitung.

Even then, the moderating influence of the soldiers' delegates was sufficient when combined with the USPD to produce a small majority on the Council in favour of accommodating the National Assembly elections.

[14] On 18 January, against Communist opposition, the Workers' and Soldiers' Council agreed to schedule popular elections for a new legislative body, a Bremen constitutional assembly for 9 March.

With armed supporters occupying a number of their offices, some left-wing members of the KPD tried to extort loans from the banks, but the action quickly collapsed, as did the attempt at a city-wide strike.

[16] In contrast to the end of the Bavarian Council Republic in Munich and to the suppression of the Spartacists in Berlin, there was only one documented case of a prisoner being shot "while trying to escape".

[17] The KPD took it as an opportunity to call in April for a political strike with the aim of reintroducing the council system and of securing the release of those fighters still incarcerated in Oslebshausen.