Bricker Amendment

They are named for their sponsor, conservative Republican Senator John W. Bricker of Ohio, who distrusted the exclusive powers of the president to involve the United States beyond the wishes of Congress.

[2] Three years later the Supreme Court of the United States explicitly ruled in Reid v. Covert that the Bill of Rights cannot be abrogated by agreements with foreign powers.

[8] Holman argued that the Genocide Convention would subject Americans to the jurisdiction of foreign courts with unfamiliar procedures and without the protections afforded under the Bill of Rights.

He said the Convention's language was sweeping and vague and offered a scenario where a white motorist who struck and killed a black child could be extradited to The Hague on genocide charges.

Duane Tananbaum, the leading historian of the Bricker Amendment, wrote "most of ABA's objections to the Genocide Convention had no basis whatsoever in reality" and his example of a car accident becoming an international incident was not possible.

[11] But Holman's hypothetical especially alarmed Southern Democrats who had gone to great lengths to obstruct federal action targeted at ending the Jim Crow system of racial segregation in the American South.

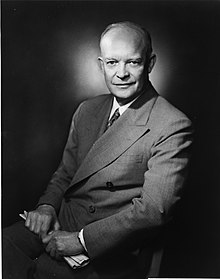

[10] President Eisenhower's aide Arthur Larson said Holman's warnings were part of "all kinds of preposterous and legally lunatic scares [that] were raised," including "that the International Court would take over our tariff and immigration controls, and then our education, post offices, military and welfare activities.

[31] In response, legal scholars such as Professor Edward Samuel Corwin of Princeton University said the language of the Constitution regarding treaties—"under the authority of the United States"—was misunderstood by Holmes, and was written to protect the 1783 peace treaty with Britain; this became "in part the source of Senator Bricker's agitation".

In the course of recognizing the USSR, letters were exchanged with the Soviet Union's foreign minister, Maxim Litvinov, to settle claims between the two countries, in an agreement neither sent to the Senate nor ratified by it.

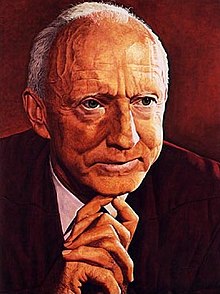

But the dissent of Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson in Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer (commonly referred to as the "steel seizure case") alarmed conservatives.

[citation needed] President Harry S. Truman had nationalized the American steel industry to prevent a strike he claimed would interfere with the prosecution of the Korean War.

Though the United States Supreme Court found this illegal, Vinson's defense of this sweeping exercise of executive authority was used to justify the Bricker Amendment.

The position of this country in the family of nations forbids trafficking innocuous generalities but demands that every State in the Union accept and act upon the Charter according to its plain language and its unmistakable purpose and intent.

"[47] Following the Second World War, various treaties were proposed under the aegis of the United Nations, in the spirit of collective security and internationalism that followed the global conflict of the preceding years.

In particular, the Genocide Convention, which made a crime of "causing serious mental harm" to "a national, ethnic, racial, or religious group" and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which contained sweeping language about health care, employment, vacations, and other subjects outside the traditional scope of treaties, were considered problematic by non-interventionists and advocates of limited government.

"[50] Frank E. Holman wrote Secretary of State George Marshall in November 1948 regarding the dangers of the Human Rights Declaration, receiving the dismissive reply that the agreement was "merely declaratory in character" and had no legal effect.

[52]Senator Bricker thought the "one world" movement advocated by those such as Wendell Willkie, Roosevelt's Republican challenger in the 1940 election, would attempt to use treaties to undermine American liberties.

[53]Frank E. Holman testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee that the Bricker Amendment was needed "to eliminate the risk that through 'treaty law' our basic American rights may be bargained away in attempts to show our good neighborliness and to indicate to the rest of the world our spirit of brotherhood.

"[57] Historians describe the Bricker Amendment as "the high water mark of the non-interventionist surge in the 1950s" and "the embodiment of the Old Guard's rage at what it viewed as twenty years of presidential usurpation of Congress's constitutional powers" which "grew out of sentiment both anti-Democrat and anti-presidential.

[55][68] George E. Reedy, aide to Senate minority leader Lyndon B. Johnson of Texas, said popular support for the measure made it "apparent from the start that it could not be defeated on a straight-out vote.

"[76] Despite the Amendment's popularity and large number of sponsors, Majority Leader Taft stalled the bill itself in the Judiciary Committee at the behest of President Eisenhower.

However, on June 10, ill health led Taft to resign as Majority Leader, and five days later, the Judiciary Committee reported the measure to the full Senate.

Erwin Griswold, dean of the Harvard Law School, and Owen Roberts, retired Justice of the United States Supreme Court, organized the Committee for the Defense of the Constitution.

[77] They were joined by such prominent Americans as attorney John W. Davis,[78] former Attorney General William D. Mitchell, former Secretary of War Kenneth C. Royall, former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, Governor Adlai Stevenson, former President Harry S. Truman, Judge John J. Parker, Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter, Denver Post publisher Palmer Hoyt, the Reverend Harry Emerson Fosdick, socialist Norman Thomas, and General Lucius D. Clay.

[80] Conservatives Clarence Manion, former dean of the University of Notre Dame Law School, and newspaper publisher Frank Gannett formed organizations to support the Amendment while a wide spectrum of groups entered the debate.

[82] Before the Second Session of the 83rd Congress convened, the Amendment "went through a complex and incomprehensible series of changes as various Senators struggled to find a precise wording that would satisfy both the President and Bricker."

"[84] Senator George was ideal as an opponent as he was a hero to conservatives of both parties for his opposition to the New Deal and his survival of President Franklin D. Roosevelt's unsuccessful effort to purge him when he sought re-election in 1938.

[88] This episode proved to be the last hurrah for the isolationist Republicans, as the younger conservatives increasingly turned to an internationalism based on aggressive anti-communism, typified by Senator Barry Goldwater.

Reid v. Covert and Kinsella v. Krueger concerned the prosecution of two servicemen's wives who killed their husbands abroad and were, under the status of forces agreements[90] in place, tried and convicted in American courts-martial.

[92]In Seery v. United States (1955) the government argued that an executive agreement allowed it to confiscate property in Austria owned by an American citizen without compensation.