The Bridge on the River Kwai

The Bridge on the River Kwai is a 1957 epic war film directed by David Lean and based on the 1952 novel written by Pierre Boulle.

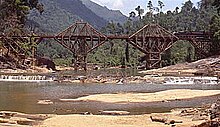

Colonel Saito, the camp commandant, informs the prisoners they will construct a railway bridge over the River Kwai connecting Thailand and Burma.

The bridge construction proceeds badly due to incompetent Japanese engineering and the prisoners' slow pace and sabotage.

Khun Yai, a village chief, and a group of Thai women guide Warden, Shears, and Joyce to the river.

Enamored with the bridge he has built, Nicholson calls to Japanese soldiers for help and attempts to stop Joyce from reaching the detonator.

The screenwriters, Carl Foreman and Michael Wilson, were on the Hollywood blacklist and, even though living in exile in England, could only work on the film in secret.

David Lean himself also claimed that producer Sam Spiegel cheated him out of his rightful part in the credits since he had had a major hand in the script.

Laughton was in his habitually overweight state, and was either denied insurance coverage or was simply not keen on filming in a tropical location.

[13] Many directors were considered for the project, among them John Ford, William Wyler, Howard Hawks, Fred Zinnemann, and Orson Welles (who was also offered a starring role).

[19] Guinness later said that he subconsciously based his walk while emerging from "the Oven" on that of his eleven-year-old son Matthew,[20] who was recovering from polio at the time, a disease that left him temporarily paralyzed from the waist down.

[23] British composer Malcolm Arnold recalled that he had "ten days to write around forty-five minutes worth of music"—much less time than he was used to.

But in Bangkok I was told that David Lean, the film's director, became mad at the extras who played the prisoners—us—because they couldn't march in time.

An estimated 80,000 to 100,000 civilians also died in the course of the project, chiefly forced labour brought from Malaya and the Dutch East Indies, or conscripted in Siam (Thailand) and Burma.

While Nicholson disapproves of acts of sabotage and other deliberate attempts to delay progress, Toosey encouraged this: termites were collected in large numbers to eat the wooden structures, and the concrete was badly mixed.

[citation needed] Julie Summers, in her book The Colonel of Tamarkan, writes that Boulle, who had been a prisoner of war in Thailand, created the fictional Nicholson character as an amalgam of his memories of collaborating French officers.

[37] Ernest Gordon, a survivor of the railway construction and POW camps described in the novel/film, stated in his 1962 book, Through the Valley of the Kwai: In Pierre Boulle's book The Bridge over the River Kwai and the film which was based on it, the impression was given that British officers not only took part in building the bridge willingly, but finished in record time to demonstrate to the enemy their superior efficiency.

Japanese engineers had been surveying and planning the route of the railway since 1937, and they had demonstrated considerable skill during their construction efforts across South-East Asia.

[39] Some Japanese viewers also disliked the film for portraying the Allied prisoners of war as more capable of constructing the bridge than the Japanese engineers themselves were,[40][41] accusing the filmmakers of being unfairly biased and unfamiliar with the realities of the bridge construction, a sentiment echoed by surviving prisoners of war who saw the film in cinemas.

However, in 1943 a railway bridge was built by Allied POWs over the Mae Klong river—renamed Khwae Yai in the 1960s as a result of the film—at Tha Ma Kham, five kilometres from Kanchanaburi, Thailand.

[47] The film was re-released in 1964 and earned a further estimated $2.6 million at the box office in the United States and Canada[48] but the following year its revised total US and Canadian revenues were reported by Variety as $17,195,000.

The site's critical consensus reads, "This complex war epic asks hard questions, resists easy answers, and boasts career-defining work from star Alec Guinness and director David Lean.

[51] Bosley Crowther of The New York Times praised the film as "a towering entertainment of rich variety and revelation of the ways of men".

[53] William Holden was also credited for his acting for giving a solid characterization that was "easy, credible and always likeable in a role that is the pivot point of the story".

[53] Edwin Schallert of the Los Angeles Times claimed the film's strongest points were for being "excellently produced in virtually all respects and that it also offers an especially outstanding and different performance by Alec Guinness.

[54] Time magazine praised Lean's directing, noting he demonstrates "a dazzlingly musical sense and control of the many and involving rhythms of a vast composition.

"[55] Harrison's Reports described the film as an "excellent World War II adventure melodrama" in which the "production values are first-rate and so is the photography.

[58] Slant stated that "the 1957 epic subtly develops its themes about the irrationality of honor and the hypocrisy of Britain's class system without ever compromising its thrilling war narrative", and in comparing to other films of the time said that Bridge on the River Kwai "carefully builds its psychological tension until it erupts in a blinding flash of sulfur and flame.

[62][63][64] In 1972, the movie was among the first selection of films released on the early Cartrivision video format, alongside classics such as The Jazz Singer and Sands of Iwo Jima.

[68] The original negative for the feature was scanned at 4K (four times the resolution in High Definition), and the colour correction and digital restoration were also completed at 4K.

The negative itself manifested many of the kinds of issues one would expect from a film of this vintage: torn frames, embedded emulsion dirt, scratches through every reel, colour fading.