Britpop

Commercially, Britpop lost out to teen pop, while artistically it segued into a post-Britpop indie movement, associated with bands such as Travis and Coldplay.

Specific influences vary: Blur drew from the Kinks and early Pink Floyd, Oasis took inspiration from the Beatles, and Elastica had a fondness for arty punk rock, notably Wire [citation needed] and both incarnations of Adam and the Ants.

[15] By 1996, Oasis's prominence was such that NME termed a number of Britpop bands (including The Boo Radleys, Ocean Colour Scene and Cast) "Noelrock", citing Gallagher's influence on their music.

[16] Journalist John Harris described these bands, and Gallagher, as sharing "a dewy-eyed love of the 1960s, a spurning of much beyond rock's most basic ingredients, and a belief in the supremacy of 'real music'".

A rise in unabashed maleness, exemplified by Loaded magazine, binge drinking and lad culture in general, would be very much part of the Britpop era.

[19] John Harris has suggested that Britpop began when Blur's fourth single "Popscene" and Suede's "The Drowners" were released around the same time in the spring of 1992.

"[20] Suede were the first of the new crop of guitar-orientated bands to be embraced by the UK music media as Britain's answer to Seattle's grunge sound.

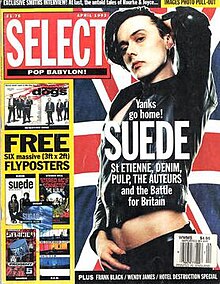

[21] In April 1993, Select magazine featured Suede's lead singer Brett Anderson on the cover with a Union Flag in the background and the headline "Yanks go home!"

The issue included features on Suede, the Auteurs, Denim, Saint Etienne and Pulp and helped start the idea of an emerging movement.

[24] The dominant musical force of the period was the grunge invasion from the United States, which filled the void left in the indie scene by the Stone Roses' inactivity.

[23] Justine Frischmann, formerly of Suede and leader of Elastica (and at the time in a relationship with Albarn) explained, "Damon and I felt like we were in the thick of it at that point ... it occurred to us that Nirvana were out there, and people were very interested in American music, and there should be some sort of manifesto for the return of Britishness.

[33] However, journalist and musician John Robb states he had used the term in the late 1980s in Sounds magazine to refer to bands such as the La's, the Stone Roses and Inspiral Carpets.

[39] Spurred on by the media, they became engaged in what the NME dubbed on the cover of its 12 August issue the "British Heavyweight Championship" with the pending release of Blur's single "Country House" and Oasis' "Roll with It" on the same day.

NME wrote about the phenomenon: Yes, in a week where news leaked that Saddam Hussein was preparing nuclear weapons, everyday folks were still getting slaughtered in Bosnia and Mike Tyson was making his comeback, tabloids and broadsheets alike went Britpop crazy.

Albarn explained to the NME in January 1997 that "We created a movement: as far as the lineage of British bands goes, there'll always be a place for us ... We genuinely started to see that world in a slightly different way.

[58] While established acts struggled, attention began to turn to the likes of Radiohead and the Verve, who had been previously overlooked by the British media.

[59] Retrospective documentaries on the movement include The Britpop Story, a BBC programme presented by John Harris on BBC Four in August 2005 as part of Britpop Night, ten years after Blur and Oasis went head-to-head in the charts,[60][61] and Live Forever: The Rise and Fall of Brit Pop, a 2003 documentary film written and directed by John Dower.

Both documentaries include mention of Tony Blair and New Labour's efforts to align themselves with the distinctly British cultural resurgence that was underway, as well Britpop artists such as Damien Hirst.

[71] Drawn from across the UK, the themes of their music tended to be less parochially centred on British, English and London life, and more introspective than had been the case with Britpop at its height.

[66] They have been seen as presenting the image of the rock star as an ordinary person, or "boy-next-door"[70] and their increasingly melodic music was criticised for being bland or derivative.

[77] The cultural and musical scene in Scotland, dubbed "Cool Caledonia" by some elements of the press,[78] produced a number of successful alternative acts, including the Supernaturals from Glasgow.

[87][88] These acts were followed by a number of bands who shared aspects of their music, including Snow Patrol from Northern Ireland and Elbow, Embrace, Starsailor, Doves, Electric Pyramid and Keane from England.

[89] Bands like Coldplay, Starsailor and Elbow, with introspective lyrics and even tempos, began to be criticised at the beginning of the new millennium as bland and sterile[92] and the wave of garage rock or post-punk revival bands, like the Hives, the Vines, the Strokes, the Black Keys and the White Stripes, that sprang up in that period were welcomed by the musical press as "the saviours of rock and roll".

[93] British groups in this vein, including the Libertines, Razorlight, Kaiser Chiefs, Arctic Monkeys and Bloc Party,[94] were viewed by some as a "second wave" of Britpop".

Viva Brother launched an update on Britpop, dubbed “Gritpop,”[97][98] with their debut album Famous First Words, although they did not receive significant support from the music press.

AG Cook’s triple album Britpop reimagines the genre’s aesthetic, featuring Charli XCX and a warped Union Jack cover.

"[106] Pulp frontman Jarvis Cocker also expressed his dislike for the term in an interview with Stephen Merchant on BBC Radio 4's Chain Reaction in 2010, describing it as a "horrible, bitty, sharp sound.