British rule in Burma

Burma is sometimes referred to as "the Scottish Colony" owing to the outsized role played by Scotsmen in colonising and running the country,[4] one of the most notable being Sir James Scott.

It was also known for the important role played by Indian elites in managing and administering the colony, especially while it was still a part of the British Raj; some historians have called this a case of co-colonialism.

[citation needed] As Burma had been one of the first Southeast Asian countries to adopt Buddhism on a large scale, it continued under the British as the officially patronised religion of most of the population.

[7] Conflict began between Burma and the British when the Konbaung dynasty decided to expand into Arakan in the state of Assam, close to British-held Chittagong in India.

[11] In 1852, the Second Anglo-Burmese War was provoked by the British, who sought the teak forests in Lower Burma as well as a port between Calcutta and Singapore.

The British were victorious in this war and as a result obtained access to the teak, oil, and rubies of their newly conquered territories.

[citation needed] In Upper Burma, the still unoccupied part of the country, King Mindon had tried to adjust to the thrust of imperialism.

The British government justified their actions by claiming that the last independent king of Burma, Thibaw Min, was a tyrant and that he was conspiring to give France more influence in the country.

[citation needed] After Britain took over all of Burma, they continued to send tribute to China to avoid offending them, but this unknowingly lowered the status they held in Chinese minds.

At the same time, the monarchy was given legitimacy by the Sangha, and monks as representatives of Buddhism gave the public the opportunity to understand national politics to a greater degree.

Furthermore, missionaries built hospitals and schools which, in the minority ethnic areas, spurred the development of writing systems for their languages, which allowed for the promotion of social progress, education and culture.

To increase the production of rice, many Burmese migrated from the northern heartland to the delta, shifting the population concentration and changing the basis of wealth and power.

[7] To prepare the new land for cultivation, farmers borrowed money from Indian Tamil moneylenders called Chettiars at high interest rates, as British banks would not grant mortgages.

As the Encyclopædia Britannica states: "Burmese villagers, unemployed and lost in a disintegrating society, sometimes took to petty theft and robbery and were soon characterized by the British as lazy and undisciplined.

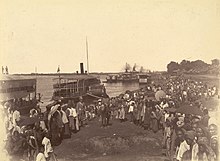

"[17] With this quickly growing economy came industrialisation to a certain degree, with a railway being built throughout the valley of the Irrawaddy, and hundreds of steamboats travelled along the river.

Thus, although the balance of trade was in favour of British Burma, the society was changed so fundamentally that many people did not gain from the rapidly growing economy.

The peasant had grown factually poorer and unemployment had increased….The collapse of the Burmese social system led to a decay of the social conscience which, in the circumstances of poverty and unemployment caused a great increase in crime.”[19] By the turn of the century, a nationalist movement began to take shape in the form of the Young Men's Buddhist Association (YMBA), modelled after the YMCA, as religious associations were allowed by the colonial authorities.

[citation needed] A new generation of Burmese leaders arose in the early twentieth century from amongst the educated classes, some of whom were permitted to go to London to study law.

Progressive constitutional reform in the early 1920s led to a legislature with limited powers, a university and more autonomy for Burma within the administration of India.

Prominent among the political activists were Buddhist monks (hpongyi), such as U Ottama and U Seinda in the Arakan who subsequently led an armed rebellion against the British and later the nationalist government after independence, and U Wisara, the first martyr of the movement to die after a protracted hunger strike in prison.

[20] In December 1930, a local tax protest by Saya San in Tharrawaddy quickly grew into first a regional and then a national insurrection against the government.

The eventual trial of Saya San, who was executed, allowed several future national leaders, including Dr Ba Maw and U Saw, who participated in his defence, to rise to prominence.

Rance calmed the situation by meeting with Aung San and convincing him to join the governor's Executive Council along with other members of the AFPFL.

[20] The new executive council, which now had increased credibility in the country, began negotiations for Burmese independence, which were concluded successfully in London as the Aung San-Attlee Agreement on 27 January 1947.

Aung San also succeeded in concluding an agreement with ethnic minorities for a unified Burma at the Panglong Conference on 12 February, celebrated since as 'Union Day'.

[20] The popularity of the AFPFL, dominated by Aung San and the socialists, was eventually confirmed when it won an overwhelming victory in the April 1947 constituent assembly elections.