British Malaya

[3] However, the British only became formally involved in Malay politics in 1771, when Great Britain tried to set up trading posts in Penang, formerly a part of Kedah.

[citation needed] Light's refusal caused the Sultan to strengthen Kedah's military forces and to fortify Prai, a stretch of beach opposite Penang.

Several factors such as the fluctuating supply of raw materials, and security, convinced the British to play a more active role in the Malay states.

During the Napoleonic Wars, between 1811 and 1815, Malacca, like other Dutch holdings in Southeast Asia, was under British occupation to prevent the French from claiming them.

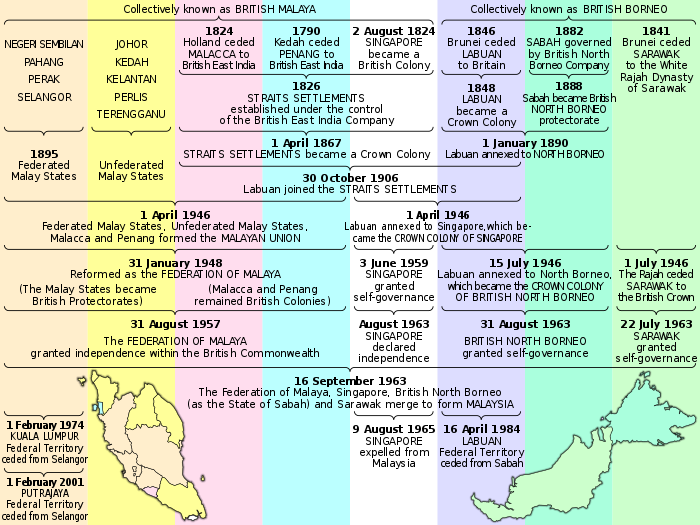

The treaty, among other things, legally transferred Malacca to British administration and officially divided the Malay world into two separate entities, laying the basis for the current Indonesian-Malaysian boundary.

[citation needed] Modern Singapore was founded in 1819 by Sir Stamford Raffles, with a great deal of help from Major William Farquhar.

The agreement stated that the British would acknowledge Tengku Hussein as the legitimate ruler of Singapore if he allowed them to establish a trading post there.

[citation needed] Until 1867, the Straits Settlements were answerable to the British administrator of the East India Company (EIC) in Calcutta.

Prior to the late 19th century, the British East India Company (EIC) was interested only in trading, and tried to avoid Malay politics.

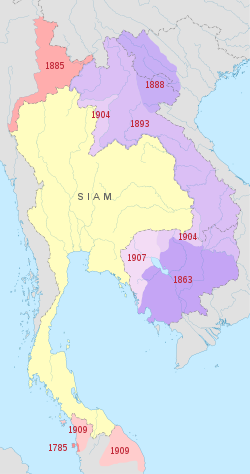

However, Siam's influence in the northern Malay states, especially Kedah, Terengganu, Kelantan and Patani, prevented the EIC from trading in peace.

In return, Siam accepted British ownership of Penang and Province Wellesley and allowed the EIC to trade in Terengganu and Kelantan unimpeded.

These skirmishes got out of hand to the point that not evenNgah Ibrahim, the Menteri Besar (chief minister), was unable to enforce the rule of law.

He then sought and gathered political support from various channels, including several of Perak's local chiefs and several British personnel with whom he had done business in the past, with the secret societies becoming their proxies in the fight for the throne.

The Governor of the Straits Settlements at that time was Sir Harry Ord who was a friend of Ngah Ibrahim, who had unresolved issues with Raja Abdullah.

With Ord's aid, Ngah Ibrahim sent sepoy troops from India to prevent Raja Abdullah from actively claiming the throne and extending control over the Chinese secret societies.

Raja Ismail, on the other hand, while not party to the agreement, was forced to abdicate due to intense external pressure applied by Clarke.

Dato' Kelana's limited popularity made him dependent on another chieftain – Sayid Abdul Rahman – who was the confederation's laksamana raja laut (roughly royal sea admiral).

In April 1874, Sir Andrew Clarke used Dato' Kelana's request as a means to build British presence in Sungai Ujong and Negeri Sembilan in general.

To streamline the administration of the Malay states, and especially to protect and further develop the lucrative trade in tin and rubber, Britain sought to consolidate and centralise control by federating Selangor, Perak, Negeri Sembilan and Pahang into the Federated Malay States (FMS), with Kuala Lumpur as its capital.

The Residents-General administered the federation but compromised by allowing the sultans to retain limited powers as the authority on Islam and Malay customs.

Despite the Sultan's political effort, he was forced to accept an advisor in 1914, becoming the last Malay state to lose its sovereignty (although British involvement in Johor began as early as 1885).

This period of slow consolidation of power into a centralised government and compromise – the sultans retain their reign but not rule in their states – would have a great impact on the later road to nationhood.

It effectively marked the transition of the idea of Malay states from a collection of separate lands governed by their own different feudal rulers, towards a federation with Westminster-style constitutional monarchy.

The First World War had a limited impact on Malaya, with notable events including the Battle of Penang and the Kelantan rebellion.

British policy in the late 19th and the early 20th century had been the centralisation of the Federated Malay States (FMS), which was headed by the High Commissioner, who was also the governor of the Straits Settlements.

[5] In 1909 however, High Commissioner Sir John Anderson expressed concerns over over-centralisation, which was marginalisation local sultans away from policymaking.

The British had a formal pro-Malay policy and the colonial administrators were careful in developing mutual trust with the Malay sultans.

[7] While the Malays supported the proposal because it would give them more powers, Chinese merchants and British planters argued against it, fearing decentralisation would affect efficiency badly and slow the building of a unified modern state.

The next High Commissioner, Sir Cecil Clementi, arriving from Hong Kong in 1930, pushed harder for decentralisation, believing that it would entice the Unfederated Malay States to join the FMS, forming a Malayan union.

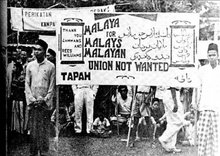

Within a year after the Second World War, the loose administration of British Malaya was finally consolidated with the formation of the Malayan Union on 1 April 1946.

1:2

. Flag of the Federated Malay States (1895–1946)

1:2

. Flag of the Federated Malay States (1895–1946)

The unfederated Malay states in blue

The

Federated Malay States

(FMS) in yellow

Federated Malay States

(FMS) in yellow

The

British Straits Settlements

in red

British Straits Settlements

in red