British National Corpus

One of the ways the BNC was to be differentiated from existing corpora at that time was to open up the data not just to academic research, but also to commercial and educational uses.

This was partly because a significant portion of the cost of the project was being funded by the British government which was logically interested in supporting documentation of its own linguistic variety.

It is a synchronic corpus, as only language use from the late 20th century is represented; the BNC is not meant to be a historical record of the development of British English over the ages.

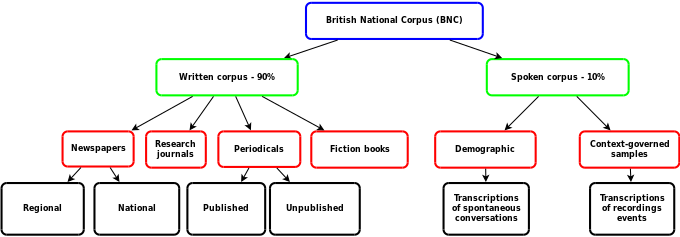

These samples were extracted from regional and national newspapers, published research journals or periodicals from various academic fields, fiction and non-fiction books, other published material, and unpublished material such as leaflets, brochures, letters, essays written by students of differing academic levels, speeches, scripts, and many other types of texts.

[6] The other part involves context-governed samples such as transcriptions of recordings made at specific types of meeting and event.

[12][13] The corpus is marked up following the recommendations of the Text Encoding Initiative (TEI) and includes full linguistic annotation and contextual information.

Intellectual property rights owners were sought for their agreement with the standard licence, including willingness to incorporate their materials in the corpus without any fees.

For example, a wide variety of imaginative texts (novels, short stories, poems, and drama scripts) were included in the BNC, but such inclusions were deemed useless as researchers were unable to easily retrieve the subgenres on which they wanted to work (e.g., poetry).

How far genres are subdivided is pre-determined for the sake of a default, but researchers have the option of making the divisions more general or specific according to their needs.

Users cannot always rely on the titles of the files as indications of their real content: For example, many texts with "lecture" in their title are actually classroom discussions or tutorial seminars involving a very small group of people, or were popular lectures (addressed to a general audience rather than to students at an institution of higher learning).

[20] Also, production pressures coupled with insufficient information led to hasty decisions, resulting in inaccuracy and inconsistency in records.

[21] The nature of the BNC as a large mixed corpus renders it unsuitable for the study of highly specific text-types or genres, as any one of them is likely to be inadequately represented and may not be recognisable from the encoding.

For example, there are very few business letters and service encounters in the BNC, and those wishing to explore their specific conventions would do better to compile a small corpus including only texts of those types.

[21] Firstly, publishers and researchers could use corpus samples to create language-learning references, syllabuses and other related tools or materials.

For example, the BNC was used by a group of Japanese researchers as a tool in their creation of an English-language–learning website for learners of English for specific purposes (ESP).

Such creation of materials that facilitate language-learning typically involves the use of very large corpora (comparable to the size of the BNC), as well as advanced software and technology.

A large amount of money, time, and expertise in the field of computational linguistics are invested in the development of such language-learning material.

This method involves a greater amount of work on the part of the language leaner and is referred to as “data-driven learning” by Tim Johns.

The corpus data used for data-driven learning is relatively smaller, and consequently the generalisations made about the target language may be of limited value.

[21] The BNC was the source of more than 12,000 words and phrases used for the production of a range of bilingual dictionaries in India in 2012, translating 22 local languages into English.

This was part of a larger movement to push for improvements in education, the preservation of India's vernacular languages, and the development of translation work.

The BNC has also been used to provide 20 million words to evaluate English subcategorization acquisition systems for the Senseval initiative for computational analysis of meaning.

[25] Hoffman & Lehmann (2000) explored the mechanisms behind speakers' ability to manipulate their large inventory of collocations which are ready for use and can be easily expanded grammatically or syntactically to adapt to the current speech situation.

In particular, approximately 1,100 lemmas were extracted from the BNC and compiled into a checklist which was consulted by the morphological generator before verbs that allowed consonant doubling were accurately inflected.

[30] Since the BNC represents a recognizable effort to collect and subsequently process such a large amount of data, it has become an influential forerunner in the field and a model or exemplary corpus on which the development of later corpora was based.

[33] The first stage of the collaborative project between the two institutions was to compile a new spoken corpus of British English from the early to mid 2010s.