British folk revival

[2] The last of these also contained some oral material and by the end of the 18th century this was becoming increasingly common, with collections including Joseph Ritson's The Bishopric Garland (1792) in northern England.

[2] In Scotland the earliest printed collection of secular music was by publisher John Forbes in Aberdeen in 1662 as Songs and Fancies: to Thre, Foure, or Five Partes, both Apt for Voices and Viols.

[3] In the 18th century publications included Playford's Original Scotch Tunes (1700), Margaret Sinkler's Music Book (1710), James Watson's Choice Collection of Comic and Serious Scots Poems both Ancient and Modern (1711), William Thomson's Orpheus caledonius: or, A collection of Scots songs (1733), James Oswald's The Caledonian Pocket Companion (1751), and David Herd's Ancient and modern Scottish songs, heroic ballads, etc.

An important catalyst for the rapid expansion of this movement around the turn of the 20th century was the work of German expatriate musicologist Carl Engel, who provocatively claimed, in a collection of essays published in 1879, that it seemed to him: rather singular that England should not possess any printed collection of its national songs with the airs as they are sung at the present day; while almost every other European nation possesses several comprehensive works of this kind.

[7] Engel went on to suggest that: there are English musicians in London and in the large provincial towns who might achieve good results if they would spend their autumnal holidays in some rural district of the country, associate with the villagers, and listen to their songs.

Among the most influential of the revival's earliest figures were the Harvard professor Francis James Child (1825–96), Sabine Baring-Gould (1834–1924), Frank Kidson (1855–1926), Lucy Broadwood (1858–1939), and Anne Gilchrist (1863–1954).

Later, major figures in this movement in England were Cecil Sharp (1859–1924) and his assistant Maud Karpeles (1885–1976) and the composers Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872–1951), George Butterworth (1885–1916), and the Australian Percy Grainger (1882–1961).

[2] Of these, Child's eight-volume collection The English and Scottish Popular Ballads (1882–92) has been the most influential on defining the repertoire of subsequent performers and the music teacher Cecil Sharp was probably the most important in understanding of the nature of folk song.

[11] As part of a general mood of growing nationalism in the period before the First World War, the Board of Education in 1906 officially sanctioned the teaching of folk songs in schools.

In any case, the search for a distinctive English voice led many composers, such as Percy Grainger (from 1905), Ralph Vaughan Williams (from about 1906) and George Butterworth (from about 1906), to use their folk music discoveries directly in composition.

These individuals, such as Sam Larner,[19] Harry Cox,[20] Fred Jordan,[21] Walter Pardon,[22] and Frank Hinchliffe,[23] released albums of their own and were revered by folk revivalists.

In Scotland the key figures were Hamish Henderson and Calum McLean who collected songs and popularised acts including Jeannie Robertson, John Strachan, Flora MacNeil and Jimmy MacBeath.

[2] The society was also responsible for sponsoring a BBC Home Service radio program, As I Roved Out, based on field recordings made by Peter Kennedy and Seamus Ennis from 1952 to 1958, which probably did more than any other single factor to introduce the general population to British and Irish folk music in the period.

In contrast to Sharp's emphasis on the rural, the activists of the second revival, particularly Lloyd, emphasized the work music of the 19th century, including sea shanties and industrial labour songs, most obviously on the album The Iron Muse (1963).

[2] Spearheaded by Lonnie Donegan’s hit "Rock Island Line" (1956) it dovetailed with the growth of café youth culture, where skiffle bands with acoustic guitars, and improvised instruments such as washboards and tea chest bass, played to teenage audiences.

[12] By the mid-1960s there were probably over 300 folk clubs in Britain, providing an important circuit for acts that performed traditional songs and tunes acoustically, where some could sustain a living by playing to a small but committed audience.

Artists such as Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger refused to confine themselves to rural or even early industrial songs, but wrote or brought burning political issues into their repertoire.

In the late 1990s, with the resurgence of traditional folk, spearheaded by children of the revival such as Eliza Carthy, Topic gained both commercial and critical success.

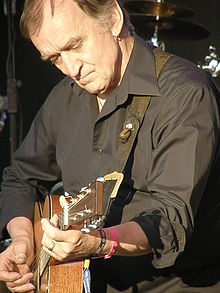

The fusing of various styles of American music with British folk also helped to create a distinctive form of fingerstyle guitar playing known as 'folk baroque', pioneered by Davy Graham, Martin Carthy, John Renbourn and Bert Jansch.

[2] Many progressive folk performers continued to retain a traditional element in their music, including Jansch and Renbourn who, with Jacqui McShee, Danny Thompson, and Terry Cox, formed Pentangle in 1967.

[31] The most successful of these was Ralph McTell, whose "Streets of London" reached number 2 in the UK Single Charts in 1974, and whose music is clearly folk, but without and much reliance on tradition, virtuosity, or much evidence of attempts at fusion with other genres.