British propaganda during World War I

Britain also placed significant emphasis on atrocity propaganda as a way of mobilising public opinion against Imperial Germany and the Central Powers during the First World War.

Britain had no propaganda agencies in place at the start of the war, which led to what Sanders and Taylor termed "an impressive exercise in improvisation".

After two conferences in September, the war propaganda agency began its work, which was largely conducted in secret and unknown by Parliament.

[6] The Bureau began its propaganda campaign on 2 September 1914, when Masterman invited 25 leading British authors to Wellington House to discuss ways of best promoting Britain's interests during the war.

During the beginning of the war, many voluntary amateur organisations and individuals also engaged in their own propaganda efforts, which occasionally resulted in tensions with Wellington House.

In January 1917, Lloyd George asked Robert Donald, the editor of the Daily Chronicle, to produce a report on current propaganda arrangements.

[10] Immediately after the production of the report, the cabinet decided to implement its plan to establish a separate Department of State to be responsible for propaganda.

However, the organisation was also criticised, and Donald argued for further reorganisation, an idea that was supported by other members of the advisory committee, such as Lords Northcliffe and Burnham.

The second report again highlighted a persistent lack of unity and co-ordination although this time, even Wellington House was rebuked for its inefficiency and haphazard nature of distribution.

A further organisation was set up under Northcliffe to deal with propaganda to enemy countries and was responsible to the War Cabinet, rather than the Minister of Information.

Special telegraph agencies were established in various European cities, including Bucharest, Bilbao and Amsterdam to facilitate the spread of information.

Various language editions were distributed, including America Latina in Spanish, O Espelho in Portuguese, Hesperia in Greek and Cheng Pao in Chinese.

James Clark's 1914 painting, The Great Sacrifice, was reproduced as the souvenir print issued by The Graphic, an illustrated newspaper, in its Christmas number.

A continuous stream of stories ensued that painted the German people as destructive barbarians, but many of the reported atrocities were exaggerated or fictitious.

Published by a committee of lawyers and historians, headed by a respected former ambassador, Lord Bryce, the report had a significant impact both in Britain and in America and made front-page headlines in major newspapers.

In response to the report, Germany published its own official response in the form of the 'White Book' (Die völkerrechtswidrige Führung des belgischen Volkskriegs "The Illegal Under International Law Leadership of the Belgian People's War"), which used fabricated evidence to justify atrocities by alleging that guerrilla warfare was being covertly backed by Allied intelligence services and fought by Belgian civilians against local units of the Imperial German Army.

Modern day research has generally supported the Bryce report as mostly accurate despite its propaganda role, and the White Book's allegations as false.

For example, Wellington House disseminated the pamphlet Belgium and Germany: Texts and Documents in 1915, which was written by Belgian Foreign Minister Davignon and featured details of alleged German war crimes.

[32] Edith Cavell was an International Red Cross nurse in Brussels who was secretly involved in La Dame Blanche, a British Intelligence network that, among many other things, helped Allied prisoners-of-war and Belgian men of military age escape through the lines.

Since engaging in any belligerent activity voided her protection as a Red Cross nurse, Cavell was court-martialed under German military law for Kriegsverrät (perfidy), found guilty and executed by firing squad in 1915.

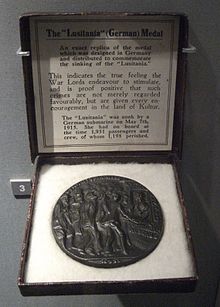

[33] British propagandists were able to use the sinking of the Lusitania as atrocity propaganda because of a commemorative medal privately struck by German artist Karl Goetz a year later.

Later, to build on anti-German sentiment, a boxed replica was produced by Wellington House that was accompanied by a leaflet explaining the barbarism of Germany.