British responses to the anti-Jewish pogroms in the Russian Empire

These anti-Jewish pogroms sparked much uncertainty for the Russian Jewish population and contributed to high levels of westbound migration from the country.

The pogroms convinced many Russian Jews to flee Russia and migrate to the west; however, the huge levels of immigration eventually transformed initial sympathy into general social disaffection.

Certainly, this influx of Russian Jews created overcrowding and is considered directly responsible for the high prices of rent and problems of housing.

Historian Bernard Gainer suggested that it was the fact that the alien immigrant was more willing to work on a Sunday, as opposed to conforming to British society, which caused most annoyance.

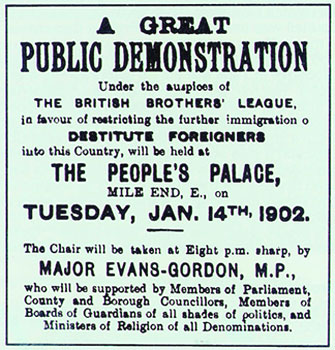

As early as the 1890s, Conservative backbenchers put pressure on Liberal governments to introduce legislation that would restrict the mass influx of central and European Jews into Britain.

The Conservative politician, Major Evans-Gordon believed that 'immigration had a deteriorating effect upon moral, financial, and social conditions of the [British] people, which resulted in lowering the general standard of life.

He argued that alien immigrants caused overcrowding and tensions in working-class communities, thereby threatening law and order;[10] however, the Liberal opposition condemned this as wrong in both principle and practice.

The Aliens Act sought to win or retain working-class votes in areas where there was a high volume of immigrants and employment was difficult to achieve.

The original restrictionist legislation also posed a significant threat to the Victorian Liberal tradition of free movement for the peoples of Britain.

The Liberals disagreed with the Conservative restrictionism and this demonstrates the contested political response in Britain regarding the effects of anti-Jewish Pogroms in Tsarist Russia.

Prominent Anglo-Jews, such as Nathaniel Mayer Rothschild and Samuel Montagu, took part in this and advocated an intervention on behalf of Russian Jewry.

This refers to the meeting at the Queen’s Hall (at Langham Place), which was once again designed to stimulate a pro-Jewish British reaction to the Russian pogroms.

Many Anglo-Jews felt that they had worked hard to be considered respectable members of society and the backward image of the Russian Jew could have threatened this.

[12] The Jewish Chronicle was a prominent voice on the persecution of Jews in Tsarist Russia and gives a valuable insight into the Anglo-Jewish outlook on the pogroms.

In the 1890s, Darkest Russia was printed as a supplement to The Jewish Chronicle and gave up-to-date news and opinions on the pogroms and preserved public interest in the wellbeing of the Russian Jewry.

[14] The paper disapproved of the actions of the Russians and applied pressure for the British government to intervene, occasionally by means of arousing public protest.

[16] The Times was a respected and conservative national newspaper, so the fact that it published such sympathetic material suggests many Britons were hostile towards despotic Russia.

The merchant bank N M Rothschild & Sons orchestrated contributions by helping to raise money and then distributing it via their foreign branches in Russia.

In the longer term, the Balfour Declaration continued traditional Conservative lines of an assertive British foreign policy that looked to help Jews abroad whilst maintaining that immigration should not reach pre-1905 levels.