British women's literature of World War I

[2] Conversely, anthologies published mid-century such as Brian Gardner's, Up the Line to Death: The War Poets of 1914-1918, contained no mention of contributions made by women.

Similarly, Jon Silkin’s 1979 anthology, Penguin Book of First World War Poetry, included the work of only two women, Anna Akhmatova and Marina Tsvetaeva.

Catherine Reilly has closely studied women's literature from World War I and its resulting impact on the relationship between gender, class, and society.

Unable to unionize as uniformly as men during this period, women faced struggles to acquire similar work hours and wages.

[10] Scholar Susan Kingsley Kent argues that, “women at the front represented the war with a tone and imagery "markedly dissimilar" from those at home.

[15] These works chronicled firsthand accounts of interaction with wounded soldiers, life in the trenches, and the difficulties of maintaining moral support from mainland Britain.

This theory was proven correct, as interest in Women's writing did not gain prominence until the early 1980s when, as part of the larger feminist conversation, critics began examining the politics of gender and war.

The First World War required the British populous to reassess their historical precedence in international involvement and domestic issues concerning class and gender.

While men were shipped to the frontlines, women remained on the home front, ensuring that Britain and its vast Empire continued to operate.

For instance, fabrication and associated industries such as, “traditional ‘women’s trades’- cotton, linen, silk, lace, tailoring, dressmaking, millinery, hat-making, pottery, and fish-gutting” saw drastic employment decline.

Literary historian David Trotter asserts that the addition of women's writing helps provide a more encompassing, and thus, stronger picture of Britain's involvement in the First World War.

[22] The women who served in non-combative roles such as ambulance drivers, nurses, and munitions workers all provided a unique perspective of life during this time.

Furthermore, it provided a strong commentary on feminist discourse that allowed women to reimagine Britain as a space where they could gain cultural capital and privilege.

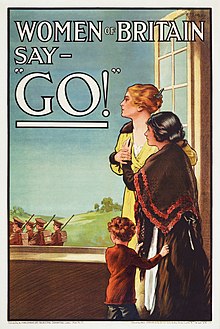

[citation needed] British male poetry often promoted the idea that women stayed at home to support the war with ‘undying love.

[28] In addition to these central themes, many female writers of this era believe that women's writing will be overshadowed by the stories of war told my men.

Many Sisters to Many Brothers expresses her distaste to the fact that the societal norm was to determine that women were more disabled than men in the war effort.

Consequently, wartime writing allowed women to challenge prevailing societal beliefs by arguing in favour of extended social and political rights such as enfranchisement.

[37] Women writers reimagined Britain's post-war social landscape by using their writing as a way to evoke sharp criticism of masculine British hegemony.

"[39] Poems allowed women to express feminist discourse concerning ideas of nationalism and sacrifice, and provided a space in which they could inform their desire to contribute more prominently in post-war Britain.

The First World War required the British populous to reassess their historical precedence in international involvement and domestic issues concerning class and gender.

While men were shipped to the frontlines, women remained on the home front, ensuring that Britain and its vast Empire continued to operate.

For instance, fabrication and associated industries such as, “traditional ‘women’s trades’- cotton, linen, silk, lace, tailoring, dressmaking, millinery, hat-making, pottery, and fish-gutting” saw drastic employment decline.

[41] Scholar Susan Kingsley Kent argues that, “women-at the front represented the war with a tone and imagery "markedly dissimilar" from those at home.