Broadway theatre

Other renowned Shakespeareans who appeared in New York in this era were Henry Irving, Tommaso Salvini, Fanny Davenport, and Charles Fechter.

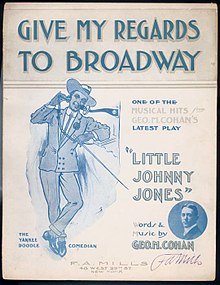

These musical comedies featured characters and situations taken from the everyday life of New York's lower classes and represented a significant step forward from vaudeville and burlesque, towards a more literate form.

They were imitated in New York by American productions such as Reginald Dekoven's Robin Hood (1891) and John Philip Sousa's El Capitan (1896), along with operas, ballets, and other British and European hits.

A Trip to Coontown (1898) was the first musical comedy entirely produced and performed by African Americans in a Broadway theatre (inspired largely by the routines of the minstrel shows), followed by the ragtime-tinged Clorindy: The Origin of the Cakewalk (1898), and the highly successful In Dahomey (1902).

Victor Herbert, whose work included some intimate musical plays with modern settings as well as his string of famous operettas (The Fortune Teller (1898), Babes in Toyland (1903), Mlle.

By the end of the 1920s, films like The Jazz Singer were presented with synchronized sound, and critics wondered if cinema would replace live theatre altogether.

Florenz Ziegfeld produced annual spectacular song-and-dance revues on Broadway featuring extravagant sets and elaborate costumes, but there was little to tie the various numbers together.

Their books may have been forgettable, but they produced enduring standards from George Gershwin, Cole Porter, Jerome Kern, Vincent Youmans, and Rodgers and Hart, among others, and Noël Coward, Sigmund Romberg, and Rudolf Friml continued in the vein of Victor Herbert.

Leaving these comparatively frivolous entertainments behind and taking the drama a step forward, Show Boat premiered on December 27, 1927, at the Ziegfeld Theatre.

[16]The 1920s also spawned a new age of American playwright with the emergence of Eugene O'Neill, whose plays Beyond the Horizon, Anna Christie, The Hairy Ape, Strange Interlude, and Mourning Becomes Electra proved that there was an audience for serious drama on Broadway, and O'Neill's success paved the way for major dramatists like Elmer Rice, Maxwell Anderson, Robert E. Sherwood, Clifford Odets, Tennessee Williams, and Arthur Miller, as well as writers of comedy like George S. Kaufman and Moss Hart.

Classical revivals also proved popular with Broadway theatre-goers, notably John Barrymore in Hamlet and Richard III, John Gielgud in Hamlet, The Importance of Being Earnest and Much Ado About Nothing, Walter Hampden and José Ferrer in Cyrano de Bergerac, Paul Robeson and Ferrer in Othello, Maurice Evans in Richard II and the plays of George Bernard Shaw, and Katharine Cornell in such plays as Romeo and Juliet, Antony and Cleopatra, and Candida.

[17] As World War II approached, a dozen Broadway dramas addressed the rise of Nazism in Europe and the issue of American non-intervention.

[18] After the lean years of the Great Depression, Broadway theatre had entered a golden age with the blockbuster hit Oklahoma!, in 1943, which ran for 2,212 performances.

"[20] Of the 1970s, Kenrick writes: "Just when it seemed that traditional book musicals were back in style, the decade ended with critics and audiences giving mixed signals.

"[21] Ken Bloom observed that "The 1960s and 1970s saw a worsening of the area [Times Square] and a drop in the number of legitimate shows produced on Broadway.

For this reason, the Theatre Development Fund was created with the purpose of assisting productions with high cultural value that likely would struggle without subsidization, by offering tickets to those plays to consumers at reduced prices.

[26] In early 1982, Joe Papp, the theatrical producer and director who established The Public Theater, led the "Save the Theatres" campaign.

[27] It was a not-for-profit group supported by the Actors Equity union to save the theater buildings in the neighborhood from demolition by monied Manhattan development interests.

[32] Faced with strong opposition and lobbying by Mayor Ed Koch's Administration and corporate Manhattan development interests, the bill was not passed.

[29] Due to the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City, Broadway theaters closed on March 12, 2020, shuttering 16 shows that were playing or were in the process of opening.

[36] Then-governor Andrew Cuomo announced that most sectors of New York would have their restrictions lifted on May 19, 2021, but he stated that Broadway theatres would not be able to immediately resume performances on this date due to logistical reasons.

In May 2021, Cuomo announced that Broadway theaters would be allowed to reopen on September 14, and the League confirmed that performances would begin to resume in the fall season.

While the League and the theatrical unions are sometimes at loggerheads during those periods when new contracts are being negotiated, they also cooperate on many projects and events designed to promote professional theatre in New York.

As Patrick Healy of The New York Times noted: Broadway once had many homegrown stars who committed to working on a show for a year, as Nathan Lane has for The Addams Family.

In 2010, some theater heavyweights like Mr. Lane were not even nominated; instead, several Tony Awards were given for productions that were always intended to be short-timers on Broadway, given that many of their film-star performers had to move on to other commitments.

[58]According to Mark Shenton, "One of the biggest changes to the commercial theatrical landscape—on both sides of the Atlantic—over the past decade or so is that sightings of big star names turning out to do plays has [sic] gone up; but the runs they are prepared to commit to has gone down.

Theatre owners, who are not generally profit participants in most productions, may waive or reduce rents, or even lend money to a show to keep it running.

Merrily We Roll Along famously skipped an out-of-town tryout and attempted to do an in-town tryout—actually preview performances—on Broadway before its official opening, with disastrous results.

For example, the first U.S. tour of The Phantom of the Opera required 26 53-foot-long (16.1 m) semi-trailers to transport all its sets, equipment, and costumes, and it took almost 10 days to properly unload all those trucks and install everything into a theater.

Tours of this type often run for weeks rather than months, and frequently feature a reduced physical production to accommodate smaller venues and tighter schedules, and to fit into fewer trucks.