Brontë family

Surnames of the Gael and the Foreigner)[2] and reproduced without question by Edward MacLysaght, cannot be accepted as correct, as there were a number of well-known scribes with this name writing in Irish in the 17th and 18th centuries and all of them used the spelling Ó Pronntaigh.

[clarification needed] After several failed attempts to remarry, Patrick accepted permanent widowerhood at the age of 47, and spent his time visiting the sick and the poor, giving sermons and administering communion.

Patrick could have sent his daughter to a less costly school in Keighley nearer home but Miss Wooler and her sisters had a good reputation and he remembered the building, which he passed when strolling around the parishes of Kirklees, Dewsbury and Hartshead-cum-Clifton where he was vicar.

The pages were filled with close, minute writing, often in capital letters without punctuation and embellished with illustrations, detailed maps, schemes, landscapes and plans of buildings, created by the children according to their specialisations.

The complexity of the stories matured as the children's imaginations developed, fed by reading the three weekly or monthly magazines to which their father had subscribed,[36] or the newspapers that were bought daily from John Greenwood's local news and stationery store.

The Leeds Intelligencer and Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, conservative and well written, but better than the Quarterly Review that defended the same political ideas whilst addressing a less-refined readership (the reason Mr. Brontë did not read it),[40] were exploited in every detail.

One of Sir Edward de Lisle's major works, Les Quatre Genii en Conseil, is inspired by Martin's illustration for John Milton's Paradise Lost.

[51] The influence of the gothic novels of Ann Radcliffe, Horace Walpole, Gregory "Monk" Lewis and Charles Maturin is noticeable,[52] and that of Walter Scott too, if only because the heroine, abandoned and left alone, resists importunities not only through her almost supernatural talents, but by her powerful temperament.

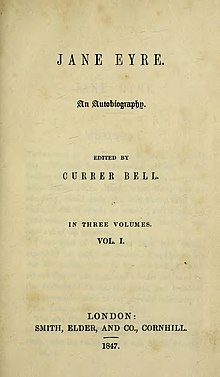

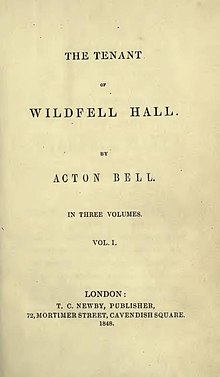

Jane Eyre, Agnes Grey, The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, Shirley, Villette and even The Professor present a linear structure concerning characters who advance through life after several trials and tribulations, to find a kind of happiness in love and virtue, recalling works of religious inspiration of the 17th century such as John Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Progress or his Grace abounding to the Chief of Sinners.

Often an artifice is employed to effect the passage from one state to another such as an unexpected inheritance, a miraculous gift, grand reunions, etc,[N 2] and in a sense it is the route followed by Charlotte's and Anne's protagonists, even if the riches they win are more those of the heart than of the wallet.

[68] He was also a good-looking man with regular features, bushy hair, very black whiskers, and wore an excited expression while sounding forth on great authors about whom he invited his students to make a pastiche on general or philosophical themes.

Neither of them felt particularly attached to their students, and only one, Mademoiselle de Bassompierre, then aged 16, later expressed any affection for her teacher Emily, which appeared to be mutual, and made her a gift of a signed, detailed drawing of a storm ravaged pine tree.

Aunt Branwell had left all her worldly goods in equal shares to her nieces and to Eliza Kingston, a cousin in Penzance,[72] which had the immediate effect of purging all their debts and providing a small reserve of funds.

The discovery of this treasure was what she recalled five years later, and according to Juliet Barker, she erased the excitement that she had felt[82] "more than surprise ..., a deep conviction that these were not common effusions, nor at all like the poetry women generally write.

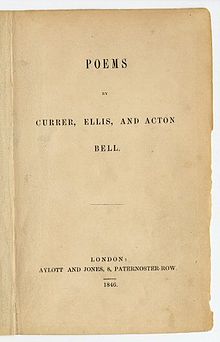

Only three copies were sold, of which one was purchased by Fredrick Enoch, a resident of Cornmarket, Warwick, who in admiration, wrote to the publisher to request an autograph—the only extant single document carrying the three authors' signatures in their pseudonyms,[86] and they continued creating their prose, each one producing a book a year later.

George Smith was extremely surprised to find two gawky, ill-dressed country girls paralysed with fear, who, to identify themselves, held out the letters addressed to Messrs. Acton, Currer and Ellis Bell.

It is a work of black Romanticism, covering three generations isolated in the cold spring of the countryside with two opposing elements: the dignified manor of Thrushcross Grange and the rambling dilapidated pile of Wuthering Heights.

The story is told in a scholarly fashion, with two narrators, the traveller and tenant Lockwood, and the housekeeper/governess, Nelly Dean, with two sections in the first person, one direct, one cloaked, which overlap each other with digressions and sub-plots that form, from apparently scattered fragments, a coherently locked unit.

[96] In 1850, a little over a year after the deaths of Emily and Anne, Charlotte wrote a preface for the re-print of the combined edition of Wuthering Heights and Agnes Grey, in which she publicly revealed the real identities of all three sisters.

More recent biographers have argued that the food, clothing, heating, medical care and discipline at Cowan Bridge were not considered sub-standard for religious schools of the time, testaments of the era's complacency about these intolerable conditions.

Despite the extreme timidity that paralysed her among strangers and made her almost incapable of expressing herself,[102] Charlotte consented to be lionised, and in London was introduced to other great writers of the era, including Harriet Martineau and William Makepeace Thackeray, both of whom befriended her.

The cause of death given at the time was tuberculosis, but it may have been complicated with typhoid fever (the water at Haworth being likely contaminated due to poor sanitation and the vast cemetery that surrounded the church and the parsonage) and hyperemesis gravidarum from her pregnancy that was in its early stage.

[110] The first biography of Charlotte was written by Elizabeth Cleghorn Gaskell at the request of Patrick Brontë, and published in 1857, helping to create the myth of a family of condemned genius, living in a painful and romantic solitude.

They ate from well filled plates of porridge in the morning and piles of potatoes were peeled each day in the kitchen while Tabby told stories about her country, or Emily revised her German grammar.

[63] Mr Patrick Brontë had one of the characters in his The Maid of Kilarney—without knowing whether it reflected a widespread opinion supporting or condemning it—say, "The education of female ought, most assuredly, to be competent, in order that she might enjoy herself, and be a fit companion for man.

But, believe me, lovely, delicate and sprightly woman, is not formed by nature, to pore over the musty pages of Grecian and Roman literature, or to plod through the windings of Mathematical Problems, nor has Providence assigned for her sphere of action, either the cabinet or the field.

Writers who followed them doubtlessly thought about them while they were creating their dark and tormented worlds such as Thomas Hardy in Jude the Obscure or Tess of the d'Urbervilles, or George Eliot with Adam Bede and The Mill on the Floss.

Charlotte's husband recalled that he had to protect his father-in-law, when on the short path to the church they had to push their way through the crowds of people wanting to reach out and touch the cape of the father of the Brontë girls.

[149] In a 2018 project curated and delivered by University of Huddersfield academic and writer Michael Stewart and the Bradford Literature Festival, four specially-commissioned poems are inscribed on four stones set in the area between the sisters' birthplace and the Haworth parsonage.

[153] The Brontë Stones Project was found to have "increased local engagement with the landscape, regenerated and preserved ancient public rights of ways, and provided an important stimulus to cultural tourism, contributing to the quality of the tourist experience".

National Portrait Gallery, London