Brown Dog affair

[2] Anti-vivisectionists commissioned a bronze statue of the dog as a memorial, unveiled on the Latchmere Recreation Ground in Battersea in 1906, but medical students were angered by its provocative plaque—"Men and women of England, how long shall these Things be?

[11] The prominent French physiologist Claude Bernard appears to have shared the distaste of his critics, who included his wife,[12] referring to "the science of life" as a "superb and dazzlingly lighted hall which may be reached only by passing through a long and ghastly kitchen".

[13] In 1875, Irish feminist Frances Power Cobbe founded the National Anti-Vivisection Society (NAVS) in London and in 1898 the British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection (BUAV).

[14] The opposition led the British government, in July 1875, to set up the first Royal Commission on the "Practice of Subjecting Live Animals to Experiments for Scientific Purposes".

[18] In the early 20th century, Ernest Starling, professor of physiology at University College London, and his brother-in-law William Bayliss, were using vivisection on dogs to determine whether the nervous system controls pancreatic secretions, as postulated by Ivan Pavlov.

By severing the duodenal and jejunal nerves in anaesthetised dogs, while leaving the blood vessels intact, then introducing acid into the duodenum and jejunum, they discovered that the process is not mediated by a nervous response, but by a new type of chemical reflex.

[19] In 1905 Starling coined the term hormone—from the Greek hormao ὁρµάω meaning "I arouse" or "I excite"—to describe chemicals such as secretin that are capable, in extremely small quantities, of stimulating organs from a distance.

The women had known each other since childhood and came from distinguished families; Lind af Hageby, who had attended Cheltenham Ladies College, was the granddaughter of a chamberlain to the king of Sweden.

[25] They attended 100 lectures and demonstrations at King's and University College, including 50 experiments on live animals, of which 20 were what Peter Mason, author of the book The Brown Dog Affair, called "full-scale vivisection".

[28] The women were present when the brown dog was vivisected, and wrote a chapter about it entitled "Fun", referring to the laughter they said they heard in the lecture room during the procedure.

[32] According to Bayliss, the dog had been given a morphine injection earlier in the day, then was anaesthetised during the procedure with six fluid ounces of alcohol, chloroform and ether (ACE), delivered from an ante-room to a tube in his trachea, via a pipe hidden behind the bench on which the men were working.

This became a point of embarrassment during the libel trial, when Bayliss's laboratory assistant, Charles Scuttle, testified that the dog had been killed with chloroform or the ACE mixture.

[32] On 14 April 1903, Lind af Hageby and Schartau showed their unpublished 200-page diary, published later that year as The Shambles of Science, to the barrister Stephen Coleridge, secretary of the National Anti-Vivisection Society.

Instead he gave an angry speech about the dog on 1 May 1903 to the annual meeting of the National Anti-Vivisection Society at St James's Hall in Piccadilly, attended by 2,000–3,000 people.

"[40] Details of the speech were published the next day by the radical Daily News (founded in 1846 by Charles Dickens), and questions were raised in the House of Commons, particularly by Sir Frederick Banbury, a Conservative MP and sponsor of a bill aimed at ending vivisection demonstrations.

According to Bayliss, the dog had been suffering from chorea, a disease that causes involuntary spasm, and that any movement reported by Lind af Hageby and Schartau had not been purposive.

[56] According to historian Hilda Kean, the Research Defence Society, a lobby group founded in 1908 to counteract the antivivisectionist campaign, discussed how to have the revised editions withdrawn because of the book's impact.

After the trial Anna Louisa Woodward, founder of the World League Against Vivisection, raised £120 for a public memorial and commissioned a bronze statue of the dog from sculptor Joseph Whitehead.

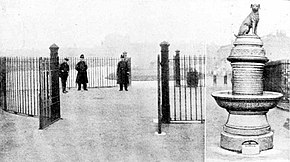

The statue sat on top of a granite memorial stone, 7 ft 6 in (2.29 m) tall, that housed a drinking fountain for human beings and a lower trough for dogs and horses.

The National Anti-Vivisection and Battersea General Hospital—opened in 1896, on the corner of Albert Bridge Road and Prince of Wales Drive, and closed in 1972—refused until 1935 to perform vivisection or employ doctors who engaged in it, and was known locally as the "antiviv" or the "old anti".

The first year of the statue's existence was a quiet one, while University College explored whether they could take legal action over it, but from November 1907 the students turned Battersea into the scene of frequent disruption.

[72] The first action was on 20 November, when undergraduate William Howard Lister led a group of medical students across the Thames to Battersea to attack the statue with a crowbar and sledgehammer.

A meeting organised by Millicent Fawcett on 5 December 1907 at the Paddington Baths Hall in Bayswater was left with chairs and tables smashed and one steward with a torn ear.

Street vendors sold handkerchiefs stamped with the date of the protest and the words, "Brown Dog's inscription is a lie, and the statuette an insult to the London University.

[86][26] For Susan McHugh of the University of New England, the political coalition of trade unionists, socialists, Marxists, liberals and suffragettes that rallied to the statue's defence reflected the brown dog's mongrel status.

In February 1908 Sir Philip Magnus, MP for the London University constituency, asked the Home Secretary, Herbert Gladstone, "whether his attention has been called to the special expense of police protection of a public monument at Battersea that bears a controversial inscription".

May we suggest that the most appropriate resting place for the rejected work of art is the Home for Lost Dogs at Battersea, where it could be "done to death", as the inscription says, with a hammer in the presence of Miss Woodword, the Rev.

Twenty thousand people signed a petition, and 1,500 attended a rally in February 1910 addressed by Lind af Hageby, Charlotte Despard and Liberal MP George Greenwood.

[98] The statue was at first hidden in the borough surveyor's bicycle shed, according to a letter his daughter wrote in 1956 to the British Medical Journal,[c] then reportedly destroyed by a council blacksmith, who melted it down.

[101] On 12 December 1985, over 75 years after the statue's removal, a new memorial to the brown dog was unveiled by actress Geraldine James in Battersea Park behind the Pump House.