Brown dwarf

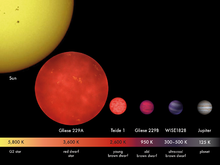

[4][5] As brown dwarfs do not undergo stable hydrogen fusion, they cool down over time, progressively passing through later spectral types as they age.

Their name comes not from the color of light they emit but from their low luminosity, falling below that of a white dwarf star but above the level of a Gas giant.

However, the time required for even the lowest-mass white dwarf to cool to this temperature is calculated to be longer than the current age of the universe; hence such objects are expected to not yet exist.

[16][17] The discovery of deuterium burning down to 0.013 M☉ (13.6 MJ) and the impact of dust formation in the cool outer atmospheres of brown dwarfs in the late 1980s brought these theories into question.

GD 165B remained unique for almost a decade until the advent of the Two Micron All-Sky Survey (2MASS) in 1997, which discovered many objects with similar colors and spectral features.

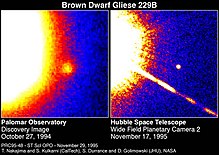

The first class "T" brown dwarf was discovered in 1994 by Caltech astronomers Shrinivas Kulkarni, Tadashi Nakajima, Keith Matthews and Rebecca Oppenheimer,[22] and Johns Hopkins scientists Samuel T. Durrance and David Golimowski.

Its near-infrared spectrum clearly exhibited a methane absorption band at 2 micrometres, a feature that had previously only been observed in the atmospheres of giant planets and that of Saturn's moon Titan.

The first confirmed class "M" brown dwarf was discovered by Spanish astrophysicists Rafael Rebolo (head of the team), María Rosa Zapatero-Osorio, and Eduardo L. Martín in 1994.

Using the most advanced stellar and substellar evolution models at that moment, the team estimated for Teide 1 a mass of 55 ± 15 MJ,[26] which is below the stellar-mass limit.

High-quality spectral data acquired by the Keck 1 telescope in November 1995 showed that Teide 1 still had the initial lithium abundance of the original molecular cloud from which Pleiades stars formed, proving the lack of thermonuclear fusion in its core.

Consequently, the central temperature and density of the collapsed cloud increase dramatically with time, slowing the contraction, until the conditions are hot and dense enough for thermonuclear reactions to occur in the core of the protostar.

Unlike stars, older brown dwarfs are sometimes cool enough that, over very long periods of time, their atmospheres can gather observable quantities of methane, which cannot form in hotter objects.

The later strengthening of this chemical compound at cooler temperatures of mid- to late T-dwarfs is explained by disturbed clouds that allows a telescope to look into the deeper layers of the atmosphere that still contains FeH.

[33] Young L/T-dwarfs (L2-T4) show high variability, which could be explained with clouds, hot spots, magnetically driven aurorae or thermochemical instabilities.

Moreover, the mass–radius relationship shows no change from about one Saturn mass to the onset of hydrogen burning (0.080±0.008 M☉), suggesting that from this perspective brown dwarfs are simply high-mass Jovian planets.

[3][48] It is also debated whether brown dwarfs would be better defined by their formation process rather than by theoretical mass limits based on nuclear fusion reactions.

[53] The Exoplanet Data Explorer includes objects up to 24 Jupiter masses with the advisory: "The 13 Jupiter-mass distinction by the IAU Working Group is physically unmotivated for planets with rocky cores, and observationally problematic due to the sin i ambiguity.

The subsequent identification of many objects like GD 165B ultimately led to the definition of a new spectral class, the L dwarfs, defined in the red optical region of the spectrum not by metal-oxide absorption bands (TiO, VO), but by metal hydride emission bands (FeH, CrH, MgH, CaH) and prominent atomic lines of alkali metals (Na, K, Rb, Cs).

[71] Young brown dwarfs have low surface gravities because they have larger radii and lower masses than the field stars of similar spectral type.

Sensitive telescopes equipped with charge-coupled devices (CCDs) have been used to search distant star clusters for faint objects, including Teide 1.

Although they do not fuse hydrogen into helium in their cores like stars, energy from the fusion of deuterium and gravitational contraction keep their interiors warm and generate strong magnetic fields.

When combined with the rapid rotation that most brown dwarfs exhibit, convection sets up conditions for the development of a strong, tangled magnetic field near the surface.

[90] "Our Chandra data show that the X-rays originate from the brown dwarf's coronal plasma which is some 3 million degrees Celsius", said Yohko Tsuboi of Chuo University in Tokyo.

[95][96] This last discovery was significant since it revealed that brown dwarfs with temperatures similar to exoplanets could host strong >1.7 kG magnetic fields.

[99] A more recent estimate from 2017 using the young massive star cluster RCW 38 concluded that the Milky Way galaxy contains between 25 and 100 billion brown dwarfs.

In a study published in Aug 2017 NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope monitored infrared brightness variations in brown dwarfs caused by cloud cover of variable thickness.

[138] If a giant planet orbits a brown dwarf across our line of sight, then, because they have approximately the same diameter, this would give a large signal for detection by transit.

[153] A 2017 study, based upon observations with Spitzer estimates that 175 brown dwarfs need to be monitored in order to guarantee (95%) at least one detection of a below earth-sized planet via the transiting method.

The orbits there would have to be of extremely low eccentricity (on the order of 10 to the minus 6) to avoid strong tidal forces that would trigger a runaway greenhouse effect on the planets, rendering them uninhabitable.

[157] In 1984, it was postulated by some astronomers that the Sun may be orbited by an undetected brown dwarf (sometimes referred to as Nemesis) that could interact with the Oort cloud just as passing stars can.