Operation Biting

Officials decided that an airborne assault followed by seaborne evacuation would be the most practicable way to surprise the garrison of the installation, seize the technology intact, and minimise casualties to the raiding force.

On the night of 27 February, after a period of intense training and several delays due to poor weather, a company of airborne troops under the command of Major John Frost parachuted into France a few miles from the installation.

The main force assaulted the villa in which the radar equipment was kept, killing several members of the German garrison and capturing the installation after a brief firefight.

[7] After the end of the Battle of France and the evacuation of British troops from Dunkirk during Operation Dynamo, much of Britain's war production and effort was channelled into RAF Bomber Command and the strategic bombing offensive against Germany.

[13] Within a few months of this discovery, Jones had identified several such radar systems, one of which was being used to detect British bombers; this was known as the "Freya-Meldung-Freya" array, named after the ancient Norse goddess.

[14] Jones was finally able to see concrete proof of the presence of the Freya system after being shown several mysterious objects visible in reconnaissance pictures taken by the RAF near Cap d'Antifer in Normandy – two circular emplacements in each of which was a rotating "mattress" antenna approximately 20 ft (6 m) wide.

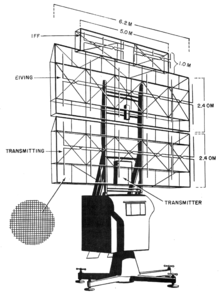

The Würzburg radar device consisted of a parabolic antenna about 10 ft (3 m) in diameter, which worked in conjunction with Freya to locate British bombers and then direct Luftwaffe night fighters to attack them.

Würzburg FuSE 62 D, also had the advantage of being much smaller than the Freya system and easier to manufacture in the quantities needed by the Luftwaffe to defend German territory.

[15][16] A request for a raid on the Bruneval site to capture a Würzburg system was passed on to Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten, the commander of Combined Operations.

[19] Believing that surprise and speed were to be the essential requirements of any raid against the installation to ensure the radar was captured, Mountbatten saw an airborne assault as the only viable method.

Cox, who had volunteered to accompany C Company for the operation; as an expert radio electronics technician, it would be his job to locate the Würzburg radar set, photograph it, and dismantle part of it for transportation back to Britain.

The beach was not land mined and had only sporadic barbed-wire defences, but it was patrolled regularly; a mobile reserve of infantry was believed to be available at one hour's notice and stationed some distance inland.

[31] It was considered that the combination of a full moon for visibility, and a rising tide to allow the landing craft to manoeuvre in shallow water, was vital for the success of the raid, which narrowed the possible dates to four days between 24 and 27 February.

[22] On 23 February, a final rehearsal exercise took place, which proved to be a failure; despite ideal weather conditions, the evacuation landing craft grounded 60 yards (180 ft) offshore and could not be shifted despite the efforts of the crews and troops.

The naval force under Commander Cook departed from Britain during the afternoon and the Whitley transport aircraft carrying C Company took off from RAF Thruxton in the evening.

[25] The aircraft crossed the English Channel without incident, but as they reached the French coast they came under heavy anti-aircraft fire; however, none of them were hit, and they successfully delivered C Company to the designated drop zone near the installation.

[32] The volume of fire rapidly increased, when enemy vehicles could be seen moving towards the villa from the nearby woods; this, in particular, worried Frost, as the radio sets the force had been issued failed to work, giving him no means of communication with his other detachments, including 'Nelson' who were tasked with clearing the evacuation beach.

Flight Sergeant Cox and several sappers arrived at this time and proceeded to dismantle the radar equipment, placing the pieces on specially designed trolleys.

[32] (see also chapter in 'Fighting Back' by Martin Sugarman on the role of German Jewish refugee Commando and Paratrooper Peter Nagel aka Newman, on the raid, and reference to the Yorks TV 1977 documentary film on the raid which includes interviews with Frost, Cox, Nagel and other survivors, and another film held by the IWM, London made in 1982) The villa was soon cleared of enemy troops once more, and when Frost returned to the beach, he found that the machine-gun nest had been destroyed by the mis-dropped troops of 'Nelson'; avoiding other enemy positions, they had reached the beach and attacked the machine-gun post from the flank.

[39] The British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, took a personal interest in the operation, and on 3 March assembled the War Cabinet to hear from Frost and several other officers who had participated in it.

Examination of the Würzburg array showed that it could be tuned to a wide range of frequencies, making it difficult to jam by the conventional means used by the British during the early years of the conflict.

[47][48] Based on what was learned in the raid, a tunable jammer aimed specifically at Würzburg (Carpet) would later be deployed, hampering German efforts to adapt to Window.

[50] The Telecommunications Research Establishment, where much of the Bruneval equipment was analysed and where British radar systems were designed and tested, was moved further inland from Swanage on the southern coast of England to Malvern, to ensure that it would not become the target of a reprisal raid by German airborne forces.