Western cattle egret

Originally native to parts of Asia, Africa and Europe, it has undergone a rapid expansion in its distribution and successfully colonised much of the rest of the world in the last century.

Their feeding habitats include seasonally inundated grasslands, pastures, farmlands, wetlands and rice paddies.

This species maintains a special relationship with cattle, which extends to other large grazing mammals; wider human farming is believed to be a major cause of their suddenly expanded range.

The cattle egret was first described in 1758 by Linnaeus in his Systema naturae as Ardea ibis,[1] but was moved to the genus Bubulcus by Charles Lucien Bonaparte in 1855.

During the breeding season, adults of the nominate western subspecies develop orange-buff plumes on the back, breast and crown, and the bill, legs and irises become bright red for a brief period prior to pairing.

[10][12] The positioning of the egret's eyes allows for binocular vision during feeding,[13] and physiological studies suggest that the species may be capable of crepuscular or nocturnal activity.

[14] Adapted to foraging on land, they have lost the ability possessed by their wetland relatives to accurately correct for light refraction by water.

[17] Cattle egrets were first sighted in the Americas on the boundary of Guiana and Suriname in 1877, having apparently flown across the Atlantic Ocean.

[19] The species first arrived in North America in 1941 (these early sightings were originally dismissed as escapees), bred in Florida in 1953, and spread rapidly, breeding for the first time in Canada in 1962.

Originally adapted to a commensal relationship with large grazing and browsing animals, it was easily able to switch to domesticated cattle and horses.

[26] Although the cattle egret sometimes feeds in shallow water, unlike most herons it is typically found in fields and dry grassy habitats, reflecting its greater dietary reliance on terrestrial insects rather than aquatic prey.

[16] The colonies are usually found in woodlands near lakes or rivers, in swamps, or on small inland or coastal islands, and are sometimes shared with other wetland birds, such as herons, egrets, ibises and cormorants.

[30] The male displays in a tree in the colony, using a range of ritualised behaviours such as shaking a twig and sky-pointing (raising his bill vertically upwards),[31] and the pair forms over three or four days.

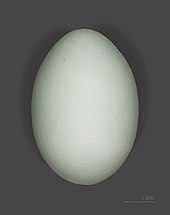

[16] There is also evidence of low levels of intraspecific brood parasitism, with females laying eggs in the nests of other cattle egrets.

[32] In the dryer habitats with fewer amphibians the diet may lack sufficient vertebrate content and may cause bone abnormalities in growing chicks due to calcium deficiency.

[38] The cattle egret feeds on a wide range of prey, particularly insects, especially grasshoppers, crickets, flies (adults and maggots[39]), and moths, as well as spiders, frogs, and earthworms.

[42] The species is usually found with cattle and other large grazing and browsing animals, and catches small creatures disturbed by the mammals.

Where numerous large animals are present, cattle egrets selectively forage around species that move at around 5–15 steps per minute, avoiding faster and slower moving herds; in Africa, cattle egrets selectively forage behind plains zebras, waterbuck, blue wildebeest and Cape buffalo.

[47] Birds of the Seychelles race also indulge in some kleptoparasitism, chasing the chicks of sooty terns and forcing them to disgorge food.

[50] It was the benefit to stock that prompted ranchers and the Hawaiian Board of Agriculture and Forestry to release the species in Hawaii.