Bullet

Bullet size is expressed by weight and diameter (referred to as "caliber") in both imperial and metric measurement systems.

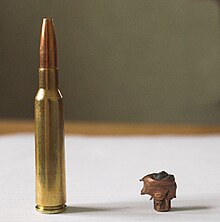

[1] Bullets do not normally contain explosives[2] but strike or damage the intended target by transferring kinetic energy upon impact and penetration.

The term bullet is from Early French, originating as the diminutive of the word boulle (boullet), which means "small ball".

The sound of gunfire (i.e. the "muzzle report") is often accompanied with a loud bullwhip-like crack as the supersonic bullet pierces through the air, creating a sonic boom.

Rifle bullets, such as that of a Remington 223 firing lightweight varmint projectiles from a 24 inch barrel, leave the muzzle at speeds of up to 4,390 kilometres per hour (2,730 mph).

[13] Shot retrieved from the wreck of the Mary Rose (sunk in 1545, raised in 1982) are of different sizes, and some are stone while others are cast iron.

(Bullets not firmly set on the powder risked exploding the barrel, with the condition known as a "short start".

[19] In 1826, Henri-Gustave Delvigne, a French infantry officer, invented a breech with abrupt shoulders on which a spherical bullet was rammed down until it caught the rifling grooves.

In 1855, a detachment of 1st U.S. Dragoons, while on patrol, traded lead for gold bullets with Pima Indians along the California–Arizona border.

Norton's bullet had a hollow base made of lotus pith that on firing expanded under pressure to engage with a barrel's rifling.

Tests proved that Greener's bullet was effective, but the military rejected it because, being two parts, they judged it as too complicated to produce.

[27] The carabine à tige, developed by Louis-Étienne de Thouvenin in 1844, was an improvement of Delvigne's design.

The bullet was conical in shape with a hollow cavity in the rear, which was fitted with a small iron cap instead of a wooden plug.

In 1855, James Burton, a machinist at the U.S. Armory at Harper's Ferry, West Virginia, improved the Minié ball further by eliminating the metal cup in the bottom of the bullet.

Roughly 90% of the battlefield casualties in the American Civil War (1861–1865) were caused by Minié balls fired from rifled muskets.

[31] Between 1854 and 1857, Sir Joseph Whitworth conducted a long series of rifle experiments and proved, among other points, the advantages of a smaller bore and, in particular, of an elongated bullet.

The surface of lead bullets fired at high velocity may melt from the hot gases behind and friction within the bore.

The streamlined boat tail design reduces this form drag by allowing the air to flow along the surface of the tapering end.

The first combination spitzer and boat-tail bullet, named balle D by its inventor Captain Georges Desaleux, was introduced as standard military ammunition in 1901, for the French Lebel Model 1886 rifle.

If a strong seal is not achieved, gas from the propellant charge leaks past the bullet, thus reducing efficiency and possibly accuracy.

However, a spin rate greater than the optimum value adds more trouble than good, by magnifying the smaller asymmetries or sometimes resulting in the bullet breaking apart in flight.

With smooth-bore firearms, a spherical shape is optimal because no matter how the bullet is oriented, its aerodynamics are similar.

These unstable bullets tumble erratically and provide only moderate accuracy; however, the aerodynamic shape changed little for centuries.

The outcome of the impact is determined by the composition and density of the target material, the angle of incidence, and the velocity and physical characteristics of the bullet.

Propulsion of the ball can happen via several methods: Bullets for black powder, or muzzle-loading firearms, were classically molded from pure lead.

The common element in all of these, lead, is widely used because it is very dense, thereby providing a high amount of mass—and thus, kinetic energy—for a given volume.

- 100-grain (6.5 g) – hollow point

- 115-grain (7.5 g) – FMJBT

- 130-grain (8.4 g) – soft point

- 150-grain (9.7 g) – round nose