Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628

While the Persians proved largely successful during the first stage of the war from 602 to 622, conquering much of the Levant, Egypt, several islands in the Aegean Sea and parts of Anatolia, the ascendancy of the emperor Heraclius in 610 led, despite initial setbacks, to a status quo ante bellum.

In return, the Sasanians ceded parts of northeastern Mesopotamia, much of Persian Armenia and Caucasian Iberia to the Byzantines, though the exact details are not clear.

[15][16][17] In order to generate a reserve in the treasury, Maurice instituted strict fiscal measures and cut army pay; which led to four mutinies.

[10][20][21] Maurice attempted to defend Constantinople by arming the Blues and the Greens – supporters of the two major chariot racing teams of the Hippodrome – but they proved ineffective.

[25] Emperor Phocas instructed general Germanus to besiege Edessa, prompting Narses to request help from the Persian king Khosrow II.

[43] Trying to increase revenues and reduce costs, Heraclius limited the number of state-sponsored personnel of the Church in Constantinople by not paying new staff from the imperial fisc.

[30][48][49][50] In Armenia, the strategically important city of Theodosiopolis (Erzurum) surrendered in 609 or 610 to Ashtat Yeztayar, because of the persuasion of a man who claimed to be Theodosius, the eldest son and co-emperor of Maurice, who had supposedly fled to the protection of Khosrow.

This defeat cut the Byzantine empire in half, severing Constantinople and Anatolia's land link to Syria, Palestine, Egypt, and the Exarchate of Carthage.

After a year-long siege, resistance in Alexandria collapsed, supposedly after a traitor told the Persians of an unused canal, allowing them to storm the city.

Heraclius faced severely decreased revenues due to the loss of provinces; furthermore, a plague broke out in 619, which further damaged the tax base and also increased fears of divine retribution.

[87] Despite disagreements over the incestuous marriage of Heraclius to his niece Martina, the clergy of the Byzantine Empire strongly backed his efforts against the Persians by proclaiming the duty of all Christian men to fight and by offering to give him a war loan consisting of all the gold and silver-plated objects in Constantinople.

[99] However, numerous attempts by the Avars and Slavs to take Thessalonica, the most important Byzantine city in the Balkans after Constantinople, ended in failure, allowing the Empire to hold onto a vital stronghold in the region.

[100] Other minor cities on the Adriatic coast like Jadar (Zadar), Tragurium (Trogir), Butua (Budva), Scodra (Shkodër), and Lissus (Lezhë) also survived the invasions.

Heraclius, planning to engage the Persian armies separately, spoke to his worried Lazic, Abasgian, and Iberian allies and soldiers, saying: "Do not let the number of our enemies disturb us.

In a mere seven days, he bypassed Mount Ararat and the 200 miles along the Arsanias River to capture Amida and Martyropolis, important fortresses on the upper Tigris.

[122] Upon hearing the news, Heraclius split his army into three parts; although he judged that the capital was relatively safe, he still sent some reinforcements to Constantinople to boost the morale of the defenders.

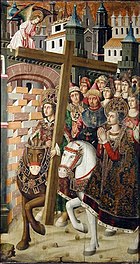

[122][123] In thanks for the lifting of the siege and the supposed divine protection of the Virgin Mary, the celebrated Akathist Hymn was written by an unknown author, possibly Patriarch Sergius or George of Pisidia.

Still, with the neutralization of Khosrow's most skilled general, Heraclius deprived his enemy of some of his best and most experienced troops, while securing his flanks prior to his invasion of Iran.

[134] Istämi sent an embassy led by the Sogdian diplomat Maniah directly to Constantinople, which arrived in 568 and offered not only silk as a gift to Justin II, but also proposed an alliance against Sasanian Iran.

[137] During the 626 siege of Constantinople, Heraclius formed an alliance with people Byzantine sources called the "Khazars", under Ziebel, now generally identified as the Western Turkic Khaganate of the Göktürks, led by Tong Yabghu,[138] plying him with wondrous gifts and the promise of marriage to the porphyrogenita Eudoxia Epiphania.

[134] The Turks, based in the Caucasus, responded to the alliance by sending 40,000 of their men to ravage the Iranian Empire in 626, marking the start of the Third Perso-Turkic War.

Edward Luttwak describes the seasonal retreat of Heraclius for the winters of 624–626 followed by a change in 627 to threaten Ctesiphon as a "high-risk, relational maneuver on a theater-wide scale" because it habituated the Persians to strategically ineffective raids that caused them to decide not to recall border troops to defend the heartland.

The Sasanians were further weakened by economic decline, heavy taxation to finance Khosrow II's campaigns, religious unrest, and the increasing power of the provincial landholders at the expense of the Shah.

[167] According to Howard-Johnston: "[Heraclius'] victories in the field over the following years and their political repercussions ... saved the main bastion of Christianity in the Near East and gravely weakened its old Zoroastrian rival.

[173] Neither empire was given much chance to recover, as within a few years they were struck by the onslaught of the Arabs, newly united by Islam,[174] which Howard-Johnston likened to "a human tsunami".

[185] According to Maurice's Strategikon, a manual of war, the Persians made heavy use of archers that were the most "rapid, although not powerful archery" of all warlike nations, and they avoided weather that hampered their bows.

In their siege of Constantinople, they constructed walls of circumvallation to prevent easy counterattack and used mantelets or wooden frames covered with animal hides to protect against defending archers.

[196] Edward Luttwak believes that the Göktürks with their "hardy horses (or ponies)" that could survive "in almost any terrain that had almost any vegetation" were essential in Heraclius's winter campaign in hilly northeast Iran in 627.

[202] Non-Greek contemporary sources include the Chronicle of John of Nikiu, which was written in Coptic but only survives in Ethiopian translation, and the History attributed to Sebeos (there is controversy over the authorship).

[209] Luttwak called Maurice's Strategikon the "most complete Byzantine field manual";[211] it provides valuable insight into the military thinking and practices of the time.