Byzantine Malta

Byzantine sources are scant on the Maltese islands, although a handful of records group them together as the Gaudomelete (Γαυδομελέτη, Gaudomelétē),[1] a term that first appears in the pseudoepigraphical Acts of Peter and Paul.

In a passage by Victor Vitensis, Bishop of Vita, historians infer that towards the end of the fifth century, the Maltese islands were conquered by Vandals from their Kingdom in North Africa, and then handed to Odoacre, the Ostrogothic king of Italy.

[7] However, as no episcopal lists survive from Africa, historians are unable to assess whether Malta had a bishop or whether the islands formed part of the African church at this early stage.

[9] Analysis of ceramics found that the Byzantines still sent navies into the Western Mediterranean well into the 9th century - confirming that Malta was a strategic stepping stone in the defence system around North Africa, Sicily and the Balearics.

[8] Although occasionally raided by Arabs naval forces, Malta - together with Sardinia and the Balearics - provided the Byzantines with a good strategic base in the central and western Mediterranean, enabling them to maintain an economic and military presence.

[8] The islands' commercial vitality, reflecting their strategic position in the Mediterranean, and a degree of autonomy which probably allowed the elites to bridge the gap between Muslim Africa and "Byzantine Italies.

[13][12] However, the first proper mention of Medieval Malta in the context of the Eastern Roman Empire is found in Procopius' Bellum Vandalicum detailing the Byzantine campaign in North Africa.

In the same passage, Procopius describes Malta as dividing the Adriatic and Tyrrhenian seas, indicating that the islands may have lied on a maritime border separating Vandal and Byzantine spheres.

A further quote in Procopius' Bellum Gothicum describing the war against the Gothic kingdom of Italy, suggests that Malta formed part of the Empire by 544, although it does not mention the islands specifically.

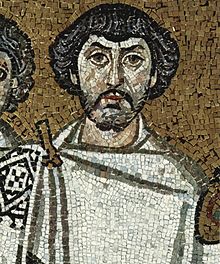

Appointed magister militum per Thracias, Artabanes was sent to replace the aged senator Liberius in command of an expedition under way against Sicily, which had recently been overrun by the Ostrogoth king Totila.

[25] The second letter, dated October 598, asks the Bishop of Syracuse to depose Lucillus for an unspecified crime, to punish his accomplices by putting them in monasteries and removing their honours.

[24] The third letter, dated to September or October 599, asks Romanus the defensor Siciliae, to make sure that Lucillus and his son hand over the property taken from the church to the new bishop, Traianus.

In the Historia syntomos, Patriarch Nikephoros details how Emperor Heraclius sent Theodorus, a magister by rank, to the island of Gaudomelete,[26] ordering the dux of the place to amputate one of his feet upon arrival.

[13] This reveals that by 637, the date of the revolt which led to the exile of John Athalarichos and Theodorus, Malta may have been governed by military officers, similar to the way Sicily and Italy were being ruled.

[32] Historians contend that the transfer of Sicilian dioceses from the Patriarchate of Rome to Constantinople, and the elevation of Syracuse to metropolitan status, obscure the ecclesiastical organisation of Malta during this period.

Fiorini and Vella note that it was sometimes the Byzantine practice to appoint a protopope (Ancient Greek: πρτωπαπάς) to vacant dioceses, and the authors see this as evidence of continuity of Byzantine ecclesiastical hierarchy, in an albeit truncated form, under the period of Muslim rule; a Christian "bishop" (ἐπίσκοπος, epískopos) found on the island after its conquest by Roger II of Sicily was probably actually such a protopope instead.

The number of Greek inscriptions found in Malta and Gozo lead historians to believe that a degree of Hellenisation occurred, in a similar manner to the process seen in Sicily.

[36] In 1768, 260 late Roman North African amphorae were found stacked in a chamber of the Kortin[H] warehouses, twenty four of which had graffiti of a religious nature on them.

[38] Large quantities of Byzantine era pottery were also found at the Kortin promontory in Marsa, with traces of a fire leading excavators to assume that the buildings and the quay were abandoned in late eight or early ninth century, with the date established due to the presence of globular amphorae on site.

There is a reference to a probable raid on Malta in the chronicles of Ibn al-Athir in 835-836, saying that Abu Iqal, from the al-Aghlab dynasty, prepared an expedition which attacked the islands near Sicily and obtained great plunder.

The Byzantines, having received timely reinforcements, resisted successfully at first, but in 870 Muhammad sent a fleet from Sicily to the island, and the capital Melite fell on 29 August 870.

[47] The siege of Melite (modern Mdina) was initially led by Halaf al-Hādim, a renowned engineer, but he was killed and replaced by Sawāda Ibn Muḥammad.

Some historians surmise that the local population sided with the Byzantine fleet, breaking a prior covenant with the Arab rulers, such that the Muslims then retaliated, imprisoned the bishop, and destroyed the islands' churches.

[42] The use of marble from the churches of Melite in the Ribat of Sousse is confirmed by an inscription which translates to:[48] Every cut slab, every marble column in this fort was brought over from the church of Malta by Ḥabaši ibn ‘Umar in the hope of meriting the approval and kindness of Allāh the Powerful and Glorious.Although al-Himyarī states that Malta remained an "uninhabited ruin" after the siege and it was only repopulated in 1048–49, archaeological evidence suggests that Mdina was already a thriving Muslim settlement by the beginning of the 11th century.