Byzantine Iconoclasm

People who engage in or support iconoclasm are called iconoclasts, Greek for 'breakers of icons' (εἰκονοκλάσται), a term that has come to be applied figuratively to any person who breaks or disdains established dogmata or conventions.

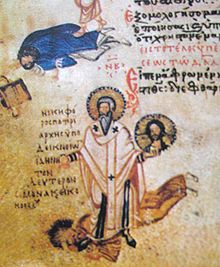

The two periods of iconoclasm in the Byzantine Empire during the 8th and 9th centuries made use of this theological theme in discussions over the propriety of images of holy figures, including Christ, the Virgin Mary (or Theotokos) and saints.

It was a debate triggered by changes in Orthodox worship, which were themselves generated by the major social and political upheavals of the seventh century for the Byzantine Empire.

Social and class-based arguments have been put forward, such as that iconoclasm created political and economic divisions in Byzantine society; that it was generally supported by the Eastern, poorer, non-Greek peoples of the Empire[6] who had to constantly deal with Arab raids.

[7] Re-evaluation of the written and material evidence relating to the period of Byzantine Iconoclasm has challenged many of the basic assumptions and factual assertions of the traditional account.[how?]

[11] Believers would, therefore, make pilgrimages to places sanctified by the physical presence of Christ or prominent saints and martyrs, such as the site of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem.

Relics, or holy objects (rather than places), which were a part of the claimed remains of, or had supposedly come into contact with, Christ, the Virgin or a saint, were also widely utilized in Christian practices at this time.

"[13] The events of the seventh century, which was a period of major crisis for the Byzantine Empire, formed a catalyst for the expansion of the use of images of the holy and caused a dramatic shift in responses to them.

This change in practice seems to have been a major and organic development in Christian worship, which responded to the needs of believers to have access to divine support during the insecurities of the seventh century.

[15] The events which have traditionally been labelled 'Byzantine Iconoclasm' may be seen as the efforts of the organised Church and the imperial authorities to respond to these changes and to try to reassert some institutional control over popular practice.

The effect on iconoclast opinion is unknown, but the change certainly caused Caliph Abd al-Malik to break permanently with his previous adoption of Byzantine coin types to start a purely Islamic coinage with lettering only.

[7] For instance, western regions such as the Cyclades contain evidence of iconoclastic loyalties from church decoration, while eastern areas such as Cyprus (then jointly-ruled by the Byzantines and the Arabs) maintained a continuous tradition of icons.

Instead, iconodules escaped Iconoclasm by fleeing to peripheral regions away from the iconoclastic imperial authority in both west (Italy and Dalmatia) and east, such as Cyprus, the southern coast of Anatolia, and eastern Pontus.

The theological arguments of the iconoclasts survive only in the form of selective quotations embedded in iconodule documents, most notably the Acts of the Second Council of Nicaea and the Antirrhetics of Nikephoros.

[31] An immediate precursor of the controversy seems to have been a large submarine volcanic eruption in the summer of 726 in the Aegean Sea between the island of Thera (modern Santorini) and Therasia, probably causing tsunamis and great loss of life.

Accounts of this event (written significantly later) suggest that at least part of the reason for the removal may have been military reversals against the Muslims and the eruption of the volcanic island of Thera,[35] which Leo possibly viewed as evidence of the Wrath of God brought on by image veneration in the Church.

According to Patricia Karlin-Hayter, what worried Germanos was that the ban of icons would prove that the Church had been in error for a long time and therefore play into the hands of Jews and Muslims.

In both sets of letters (the earlier ones concerning Constantine, the later ones Thomas), Germanos reiterates a pro-image position while lamenting the behavior of his subordinates in the church, who apparently had both expressed reservations about image worship.

In the process of destroying or obscuring images, Leo is said to have "confiscated valuable church plate, altar cloths, and reliquaries decorated with religious figures",[37] but he took no severe action against the former patriarch or iconophile bishops.

Despite his successes as an emperor, both militarily and culturally, this has caused Constantine to be remembered unfavorably by a body of source material that is preoccupied with his opposition to image veneration.

Constantine seems to have been closely involved with the council, and it endorsed an iconoclast position, with 338 assembled bishops declaring, "the unlawful art of painting living creatures blasphemed the fundamental doctrine of our salvation--namely, the Incarnation of Christ, and contradicted the six holy synods.

Constantine himself wrote opposing the veneration of images, while John of Damascus, a Syrian monk living outside of Byzantine territory, became a major opponent of iconoclasm through his theological writings.

A possible reason for this interpretation is the desire in some historiography on Byzantine Iconoclasm to see it as a preface to the later Protestant Reformation in western Europe, which was opposed to monastic establishments.

[citation needed] The surviving sources accuse Constantine V of moving against monasteries, having relics thrown into the sea, and stopping the invocation of saints.

[44] In June 813, a month before the coronation of Leo V, a group of soldiers broke into the imperial mausoleum in the Church of the Holy Apostles, opened the sarcophagus of Constantine V, and implored him to return and save the empire.

Leo was succeeded by Michael II, who in an 824 letter to the Carolingian emperor Louis the Pious lamented the appearance of image veneration in the church and such practices as making icons baptismal godfathers to infants.

The Law of Moses and the Prophets cooperated to remove this ruin...But the previously mentioned demiurge of evil...gradually brought back idolatry under the appearance of Christianity.

As Cyril Mango writes, "The legacy of Nicaea, the first universal council of the Church, was to bind the emperor to something that was not his concern, namely the definition and imposition of orthodoxy, if need be by force."

The plain Iconoclastic cross that replaced a figurative mosaic by Emperor Constantine V in the apse of Hagia Irene in Constantinople is itself an almost unique survival,[14] but careful inspection of some other buildings reveals similar changes.

[58] The period of Iconoclasm decisively ended the so-called Byzantine Papacy under which, since the reign of Justinian I two centuries before, the popes in Rome had been initially nominated by, and later merely confirmed by, the emperor in Constantinople, and many of them had been Greek-speaking.