Madam C. J. Walker

Villa Lewaro, Walker's lavish estate in the Irvington neighborhood of Indianapolis, Indiana served as a social gathering place for the African-American community.

Breedlove also stated that she had only three months of formal education, which she undertook during Sunday school literacy lessons at the church she attended during her earlier years.

[17] Breedlove suffered severe dandruff and other scalp ailments, including baldness, due to skin disorders and the application of harsh products to cleanse hair and wash clothes.

[9] Around the time of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition (World's Fair at St. Louis in 1904), Breedlove became a commission agent selling products for Annie Turnbo Malone, an African-American haircare entrepreneur and owner of the Poro Company.

[13] In July 1905, when Breedlove was 37 years old, she moved with Lelia to Denver, Colorado, where she initially continued to sell products for Malone while developing her own haircare business.

However, the two businesswomen had a falling-out when Malone accused Breedlove of stealing her formula, a mixture of petroleum jelly and sulfur that had been in use for a hundred years.

[8][13] In 1906, Walker put A'Lelia in charge of the mail-order operation in Denver while she and Charles traveled throughout the southern and eastern United States to expand the business.

[16][9][18][22] In 1908, Walker and her husband relocated to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where they opened a beauty parlor and established Lelia College[23] to train "hair culturists".

[24] A'Lelia also persuaded her mother to establish an office and beauty salon in New York City's growing Harlem neighborhood in 1913; it became a center of African-American culture.

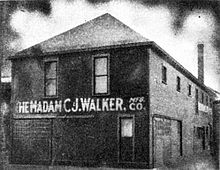

[25] Walker later built a factory, hair salon, and beauty school to train her sales agents and added a laboratory to help with research.

[18] Walker also assembled a staff that included Freeman Ransom, Robert Lee Brokenburr, Alice Kelly, and Marjorie Joyner, among others, to assist in managing the growing company.

Others have written the agents focused on door-to-door sales as they visited houses around the United States and in the Caribbean offering Walker's hair pomade and other products packaged in tin containers carrying her image.

Heavy advertising, primarily in African-American newspapers and magazines, and Walker's frequent travels to promote her products helped make her well-known in the United States.

In addition to training in sales and grooming, Walker showed other black women how to budget and build businesses and encouraged them to become financially independent.

In 1917, inspired by the model of the National Association of Colored Women, Walker began organizing her sales agents into state and local clubs.

[16] Walker's name became even more widely known by the 1920s, after her death, as her company's business market expanded beyond the United States to Cuba, Jamaica, Haiti, Panama, and Costa Rica.

In 1912, Walker addressed an annual gathering of the National Negro Business League (NNBL) from the convention floor, where she declared: "I am a woman who came from the cotton fields of the South.

Other beneficiaries included Indianapolis's Flanner House and Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church; Mary McLeod Bethune's Daytona Education and Industrial School for Negro Girls (which later became Bethune-Cookman University) in Daytona Beach, Florida; the Palmer Memorial Institute in North Carolina; and the Haines Normal and Industrial Institute in Georgia.

Walker intended for Villa Lewaro, which cost $250,000 to build, to become a gathering place for community leaders and to inspire other African Americans to pursue their dreams.

[27][28][29] Walker moved into the house in May 1918 and hosted an opening event to honor Emmett Jay Scott, at that time the Assistant Secretary for Negro Affairs of the U.S. Department of War.

[16] Also, from 1917 until her death, Walker was a member of the Committee of Management of the Harlem YWCA, influencing the development of training in beauty skills to young women by the organization.

In 1918, the National Association of Colored Women's Clubs (NACWC) honored Walker for making the largest individual contribution to help preserve Frederick Douglass's Anacostia house.

It included the company's offices and factory, a theater, a beauty school, a hair salon and barbershop, a restaurant, a drugstore, and a ballroom for the community.

[38][39] In 2006, playwright and director Regina Taylor wrote The Dreams of Sarah Breedlove, recounting the history of Walker's struggles and success.

[42] These products replace the line that was launched on March 4, 2016, by Sundial Brands, a skincare and haircare company, in collaboration with Sephora in honor of Walker's legacy.

The line "Madam C. J. Walker Beauty Culture" comprised four collections focused on using natural ingredients to care for different hair types.

The portrayal of Annie Malone as Addie Monroe, another black female self-made millionaire as a villain and the daughter of Walker as a lesbian were some of the complaints by audiences.

[45][46] Biographer A'Lelia Bundles wrote about the behind-the-scenes experience of producing Self Made in "Netflix's Self-Made Suffers from Self-Inflicted Wounds".