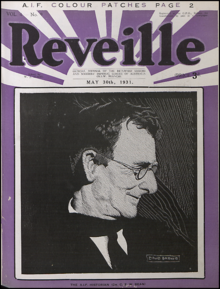

Charles Bean

[6] While at Clifton, Bean developed an interest in literature and in 1898 won a scholarship to Hertford College, Oxford, taking a Masters of Arts in 1903 and a Bachelor of Civil Law in 1904.

"[10] In 1908 Bean abandoned law for journalism and, at the suggestion of Paterson, applied to join the staff of the SMH[11] In mid-1908, as a junior reporter he covered the waterside workers' strike and wrote a twelve-part series of articles on country NSW under the banner 'Barrier Railway.

[20][21][8] Early in 1913, Bean returned to Sydney as a leader-writer for the SMH, continuing to write about town planning and the steps that should be taken to control the city's future development.

[34] He was accompanied by Private Arthur Bazley, his formally designated batman, who became his invaluable assistant, researcher, lifelong friend and, later, acting Director of the AWM.

These diary entries also reflected the feelings and views of an individual who witnessed those events which ranged from battles to planning and discussions in headquarters, and to men at rest and in training.

As a condition of the gift of his papers to the AWM in 1942 he stipulated that it attach to every diary and notebook a caveat which was amended in 1948 to read, in part: 'These records should … be used with great caution, as relating only what their author, at the time of writing, believed'.

The English reporter betrayed surprise that untrained colonials had done so well; Bean was seeing what he hoped to see: the Australian soldiers, as he described them, were displaying qualities he had observed out in the country".

[9][6] For the help he gave to wounded men under fire on the night of 8 May 1915 during the Australian charge at Krithia, Bean was recommended for the Military Cross, for which as a civilian he was not eligible.

[52] Bazley had left for the island of Imbros on the previous night with 150 pieces of art, prose and verse, created under conditions of extreme hardship by soldiers in the trenches, and intended for a New Year magazine.

In February 1917, he wrote to the War Records Office with a suggestion that important documents – such as The Anzac Book manuscript and rejected contributions – be preserved so that they could one day be deposited in a museum.

[60] Having missed the poorly conceived and executed attack at Fromelles on 19 July 1916, the first big Australian action in France which had resulted in heavy losses, Bean was there the following morning moving among survivors getting their stories.

[64] The carnage on the Somme caused Bean to conceive the idea of a memorial where Australia could commemorate its war dead and view the relics its troops collected.

[83] On 11 November 1918, Armistice Day, Bean's diary records that he returned to Fromelles with a photographer to revisit the battlefields where over two years earlier on the night of 19–20 July 1916, the Australians had endured their brutal introduction of warfare on the Western Front: "...we found the old no man's land simply full of our dead”.

Before 1914 he had employed serenely the notion of an English race, and briskly defended White Australia.…By 1949 he was arguing for admission of limited numbers of immigrants from Asia rather than perpetrating a 'quite senseless colour line'.

There are instances in the tract where Bean uses inclusive language such as: "…the making of a nation is in the hands of every man and woman, every boy and girl", and "We must plan for the education of every person in the State in body, mind and character".

[98][99][100] In February–March 1919, on his homeward journey, Bean led a group of eight Australians including artist George Lambert, photographer Hubert Wilkins, and scribe John Balfour on a visit to Gallipoli.

[7] With a small staff, Bean took up his appointment as official historian in 1919, based first in the rural setting of Tuggeranong homestead, near the then unbuilt Federal Capital, Canberra, and later at Victoria Barracks, Sydney.

"[114] Bean's paper to the Royal Australian Historical Society in 1938, "The Writing of the Official History of Great War – Sources, Methods and Some Conclusions" provided a list of forty main classes of records on which the work was based.

[115][116] One of the sources was the 45,000 responses to the 60,000 questionnaires ("Roll of Honour" forms) sent out in 1919 to the "next of kin of the fallen", for the personal footnotes of the histories which, as Bean recorded, “have been noted by critics as an interesting and peculiar feature of the work”.

"[124] According to Pegram, historians generally agree that Bean's belief in rural virtues does not adequately explain how the AIF transformed from an organisation of neophytes in 1914 to the effective fighting force that contributed to Germany’s defeat in 1918.

[125] Nevertheless, Stanley maintained that while later studies have elaborated, revised and challenged many aspects of it, the Official History retains its integrity as the single greatest source of interpretation of Australia’s part in the First World War.

[127][128] Accordingly, the style of the AWM reflects Bean's desire for the building to at once be museum, monument, memorial, temple and shrine to Australians who lost their lives and suffered as a result of war.

[129] Bean's vision for the AWM appears on the wall inside its front doors: "Here is their spirit, in the heart of the land they loved; and here we guard the record which they themselves made.

[134] As the general editor and principal author of the Official History Bean was also associated with the AWM as publisher and as a donor and adviser on the collections including post-war art commissions.

Most reflected his concern to improve the nature of Australian society and the welfare of its people, particularly in relation to education, causing him to be described by Rees as a "social missionary".

Bean, along with other historians, had lobbied for this initiative as prior to that time Australia possessed no national archives resulting in World War I records being destroyed.

The Mission had retraced the landing and the fight up the range, and with the assistance of a Turkish officer, Major Zeki Bey who served through the campaign, was able to follow the Turk defence system.

[161] Towards the end of his life Bean planned to write a series of biographies but only one was written: Two Men I Knew: William Bridges and Brudenell White, Founders of the A.I.F., which was published in 1957.

"[170][171] According to the Australian Media Hall of Fame: "It is his [Bean's] extraordinary, painstakingly detailed (and often harrowing) private notes and diaries written during the war that remain one of his greatest achievements.

They describe the activities, conditions and experiences of the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) from the perspective of an eye-witness and a journalist who sought the best possible evidence from a wide range of participants, including enlisted men of all ranks, the military hierarchy and political decision-makers.