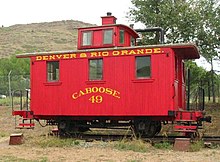

Caboose

Cabooses provide shelter for crew at the end of a train, who were formerly required in switching and shunting; as well as in keeping a lookout for load shifting, damage to equipment and cargo, and overheating axles.

The caboose also served as the conductor's office, and on long routes, included sleeping accommodations and cooking facilities.

Nowadays, they are generally only used on rail maintenance or hazardous materials trains, as a platform for crew on industrial spur lines when it is required to make long reverse movements, or on heritage and tourist railroads.

Eighteenth century French naval records also make reference to a cambose or camboose, which described both the food preparation cabin on a ship's main deck and its stove.

"[6] As the first railroad cabooses were wooden shanties erected on flat cars as early as the 1830s,[7] they would have resembled the cook shack on a ship's deck.

They also inspected the train for problems such as shifting loads, broken or dragging equipment, and hot boxes (overheated axle bearings, a serious fire and derailment threat).

For longer trips, the caboose provided minimal living quarters, and was frequently personalized and decorated with pictures and posters.

[11] Coal or wood was originally used to fire a cast-iron stove for heat and cooking, later giving way to a kerosene heater.

They were without legs, bolted directly to the floor, and featured a lip on the top surface to keep pans and coffee pots from sliding off.

They also had a double-latching door, to prevent accidental discharge of hot coals caused by the rocking motion of the caboose.

The Kansas City Southern Railway was unique in that it bought cabooses with a stainless steel car body, and so was not obliged to paint them.

Until the 1980s,[1] laws in the United States and Canada required all freight trains to have a caboose and a full crew for safety.

Technology eventually advanced to a point where the railroads, in an effort to save money by reducing crew members, stated that cabooses were unnecessary.

[12] The ETD also detects movement of the train upon start-up and radios this information to the engineers so they know all of the slack is out of the couplings and additional power could be applied.

A 1982 Presidential Emergency Board convened under the Railway Labor Act directed United States railroads to begin eliminating caboose cars where possible to do so.

The form of cabooses varied over the years, with changes made both to reflect differences in service and improvements in design.

The invention of the cupola caboose is generally attributed to T. B. Watson, a freight conductor on the Chicago and North Western Railway.

The bay window gained favor with many railroads because it eliminated the need for additional clearances in tunnels and overpasses.

On the West Coast, the Milwaukee Road and the Northern Pacific Railway used these cars, converting over 900 roof top cabooses to bay windows in the late 1930s.

[15] Milwaukee Road rib-side bay window cabooses are preserved at New Lisbon, Wisconsin, the Illinois Railway Museum, the Mt.

The Western Pacific Railroad was an early adopter of the type, building their own bay window cars starting in 1942 and acquiring this style exclusively from then on.

It is used in transfer service between rail yards or short switching runs, and as such, lacks sleeping, cooking or restroom facilities.

CSX uses former Louisville & Nashville short bay window cabooses and former Conrail waycars as pushing platforms.

[citation needed] Cabooses have also become popular for collection by railroad museums and for city parks and other civic uses, such as visitor centers.

Large railroads also use cabooses as "shoving platforms" or in switching service where it is convenient to have crew at the rear of the train.