Cadence

[2] A harmonic cadence is a progression of two or more chords that concludes a phrase, section, or piece of music.

The Harvard Concise Dictionary of Music and Musicians says, "This cadence is a microcosm of the tonal system, and is the most direct means of establishing a pitch as tonic.

This is generally considered the strongest type of cadence and often found at structurally defining moments.

[8] Music theorist William Caplin writes that the perfect authentic cadence "achieves complete harmonic and melodic closure.

Due to its being a survival from modal Renaissance harmony this cadence gives an archaic sound, especially when preceded by v (v–iv6–V).

[14] A characteristic gesture in Baroque music, the Phrygian cadence often concluded a slow movement immediately followed ("attacca") by a faster one.

But in one very unusual occurrence – the end of the exposition of the first movement of Brahms' Clarinet Trio, Op.

[20] An early suggestion of the Moravian cadence in classical music occurs in Antonín Dvořák’s New World Symphony.

At the beginning of the final movement of Gustav Mahler's 9th Symphony, the listener hears a string of many deceptive cadences progressing from V to IV6.

[citation needed] One of the most striking uses of this cadence is in the A-minor section at the end of the exposition in the first movement of Brahms' Third Symphony.

The music progresses to an implied E minor dominant (B7) with a rapid chromatic scale upwards but suddenly sidesteps to C major.

For example, the Pink Floyd song "Bring the Boys Back Home" ends with such a cadence (at approximately 0:45–50).

It refers to the use of a major chord of the tonic at the end of a musical section that is either modal or in a minor key.

[31] This example from a well-known 16th-century lamentation shows a cadence that appears to imply the use of an upper leading-tone, a debate over which was documented in Rome c. 1540.

The first theoretical mention of cadences comes from Guido of Arezzo's description of the occursus in his Micrologus, where he uses the term to mean where the two lines of a two-part polyphonic phrase end in a unison.

[33] According to Carl Dahlhaus, "as late as the 13th century the half step was experienced as a problematic interval not easily understood, as the remainder between the perfect fourth and the ditone:[34] In a melodic half step, listeners of the time perceived no tendency of the lower tone toward the upper, or the upper toward the lower.

Instead, musicians avoided the half step in clausulas because, to their ears, it lacked clarity as an interval.

Similar to a clausula vera, it includes an escape tone in the upper voice, which briefly narrows the interval to a perfect fifth before the octave.

The classical and romantic periods of musical history provide many examples of the way the different cadences are used in context.

53 features a minor key passage where an authentic (perfect) cadence precedes a deceptive (interrupted) one: Dvořák’s Slavonic Dance, Op.

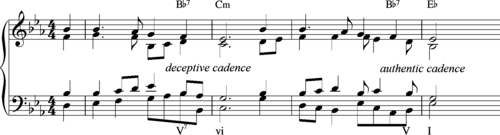

2 features deceptive (interrupted), half (imperfect) and authentic (perfect) cadences within its first sixteen bars:Debussy's Prelude “La fille aux cheveux de lin” (see also above) concludes with a passage featuring a deceptive (interrupted) cadence that progresses, not from V–VI, but from V–IV: Some varieties of deceptive cadence that go beyond the usual V–VI pattern lead to some startling effects.

For example, a particularly dramatic and abrupt deceptive cadence occurs in the second Presto movement of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No.

"[45] Hermann Keller describes the effect of this cadence as follows: "the splendour of the end with the famous third inversion of the seventh chord, who would not be enthralled by that?

49, composed over a century later in 1841, features a similar harmonic jolt: A deceptive cadence is a useful means for extending a musical narrative.

In the closing passage of Bach’s Prelude in F minor from Book II of the Well-Tempered Clavier, the opening theme returns and seems headed towards a possible final resolution on an authentic (perfect) cadence.

[48] The descending diminished seventh chord half-step cadence is assisted by two common tones.

[4] The example below shows a characteristic rhythmic cadence (i.e. many of the cadences in this piece share this rhythmic pattern) at the end of the first phrase (in particular the last two notes and the following rest, contrasted with the regular pattern set up by all the notes before them) of J.S.