Calvin Coolidge

[3] He was known for his hands-off governing approach and pro-business stance; biographer Claude Fuess wrote: "He embodied the spirit and hopes of the middle class, could interpret their longings and express their opinions.

Coolidge explained Garman's ethics forty years later:[T]here is a standard of righteousness that might does not make right, that the end does not justify the means, and that expediency as a working principle is bound to fail.

Gilbert explains in his book how Coolidge displayed all ten of the symptoms listed by the American Psychiatric Association as evidence of major depressive disorder following Calvin Jr.'s sudden death.

[38] Instead of vying for another term in the State House, Coolidge returned home to his growing family and ran for mayor of Northampton when the incumbent Democrat retired.

[44] When the new Progressive Party declined to run a candidate in his state senate district, Coolidge won reelection against his Democratic opponent by an increased margin.

[64] Peters, concerned about sympathy strikes by the firemen and others, called up some units of the Massachusetts National Guard stationed in the Boston area pursuant to an old and obscure legal authority, and relieved Curtis of duty.

[76] Although he was personally opposed to Prohibition, he vetoed a bill in May 1920 that would have allowed the sale of beer or wine of 2.75% alcohol or less, in Massachusetts in violation of the Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

The story about it was related by Frank B. Noyes, President of the Associated Press, to their membership at their annual luncheon at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel, when toasting and introducing Coolidge, who was the invited speaker.

"[89] Alice Roosevelt Longworth, a leading Republican wit, underscored Coolidge's silence and his dour personality: "When he wished he were elsewhere, he pursed his lips, folded his arms, and said nothing.

"[90] Coolidge and his wife, Grace, who was a great baseball fan, once attended a Washington Senators game and sat through all nine innings without saying a word, except once when he asked her the time.

"[93] Some historians suggest that Coolidge's image was created deliberately as a campaign tactic,[94] while others believe his withdrawn and quiet behavior to be natural, deepening after the death of his son in 1924.

[97] His father, a notary public and justice of the peace, administered the oath of office in the family's parlor by the light of a kerosene lamp at 2:47 a.m. on August 3, 1923, whereupon the new President of the United States returned to bed.

Coolidge returned to Washington the next day, and was sworn in again by Justice Adolph A. Hoehling Jr. of the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia, to forestall any questions about the authority of a state official to administer a federal oath.

Harry A. Slattery reviewed the facts with him, Harlan F. Stone analyzed the legal aspects for him and Senator William E. Borah assessed and presented the political factors.

By that time, two-thirds of them were already citizens, having gained it through marriage, military service (veterans of World War I were granted citizenship in 1919), or the land allotments that had earlier taken place.

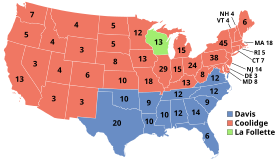

The convention soon deadlocked, and after 103 ballots, the delegates finally agreed on a compromise candidate, John W. Davis, with Charles W. Bryan nominated for vice president.

"[112] Even as he mourned, Coolidge ran his standard campaign, not mentioning his opponents by name or maligning them, and delivering speeches on his theory of government, including several that were broadcast over the radio.

He left the administration's industrial policy in the hands of his activist Secretary of Commerce, Herbert Hoover, who energetically used government auspices to promote business efficiency and develop airlines and radio.

[119] Historian Robert Sobel offers some context of Coolidge's laissez-faire ideology, based on the prevailing understanding of federalism during his presidency: "As Governor of Massachusetts, Coolidge supported wages and hours legislation, opposed child labor, imposed economic controls during World War I, favored safety measures in factories, and even worker representation on corporate boards.

The bill proposed a federal farm board that would purchase surplus production in high-yield years and hold it (when feasible) for later sale or sell it abroad.

[132] After McNary-Haugen's defeat, Coolidge supported a less radical measure, the Curtis-Crisp Act, which would have created a federal board to lend money to farm co-operatives in times of surplus; the bill did not pass.

In the 1924 presidential election his opponents (Robert La Follette and John Davis), and his running mate Charles Dawes, often attacked the Klan, but Coolidge avoided the subject.

[149] On June 6, 1924, Coolidge delivered a commencement address at historically black, non-segregated Howard University, in which he thanked and commended African Americans for their rapid advances in education and their contributions to U.S. society over the years, as well as their eagerness to render their services as soldiers in the World War, all while being faced with discrimination and prejudices at home.

It set fixed annual amounts for Germany's World War I reparations payments and authorized a large loan, mostly from American banks, to help stabilize and stimulate the German economy.

[160] The Kellogg–Briand Pact of 1928, named for Coolidge's Secretary of State, Frank B. Kellogg, and French foreign minister Aristide Briand, was also a key peacekeeping initiative.

[170] For Canada, Coolidge authorized the St. Lawrence Seaway, a system of locks and canals that would provide large vessels passage between the Atlantic Ocean and the Great Lakes.

During this period, he also served as chairman of the Non-Partisan Railroad Commission, an entity created by several banks and corporations to survey the country's long-term transportation needs and make recommendations for improvements.

[193] Historians have criticized Coolidge for his lack of assertiveness and have characterized him as a "do nothing president" who only enjoyed high public approval because he was in office when things were going naturally well around the world.

[194][195] Some historians have also scrutinized Coolidge for his signing of laws that broadened federal regulatory authority and claimed it paved the way for corruption in future presidential administrations.

[208][209] When Charles Lindbergh arrived in Washington on a U.S. Navy ship after his celebrated 1927 trans-Atlantic flight, President Coolidge welcomed him back to the U.S. and presented him with the Medal of Honor;[210] the event was captured on film.

Front row, left to right: Harry Stewart New , John W. Weeks , Charles Evans Hughes , Coolidge, Andrew Mellon , Harlan F. Stone , Curtis D. Wilbur .

Back row, left to right: James J. Davis , Henry C. Wallace , Herbert Hoover , Hubert Work .