Calypso music

[4] The Africans brought to toil on sugar plantations, were stripped of all connections to their homeland and family and were not allowed to talk to each other.

Modern calypso, however, began in the 19th century as a fusion of disparate elements ranging from the masquerade song lavway, French Creole belair and the calinda stick-fighting chantwell.

[5] Calypso's early rise was closely connected with the adoption of Carnival by Trinidadian slaves, including canboulay drumming and the music masquerade processions.

[6] Perhaps due to the constraints of the wartime economy, no recordings of note were produced until the late 1920s and early 1930s, when the "golden era" of calypso would cement the style, form, and phrasing of the music.

Calypsonians pushed the boundaries of free speech as their lyrics spread news of any topic relevant to island life, including speaking out against political corruption.

Even with this censorship, calypsos continued to push boundaries, with a variety of ways to slip songs past the scrutinizing eyes of the editor.

Double entendre, or double-speak, was one way, as was the practice of denouncing countries such as Germany and its annexation of Poland, while making pointed references toward the colonial government's policies in Trinidad.

An entrepreneur named Eduardo de Sá Gomes played a significant role in spreading calypso in its early days.

[7] Lord Invader was quick to follow, and stayed in New York City after a protracted legal case involving the theft of his song "Rum and Coca-Cola", a hit by the Andrews Sisters.

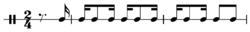

In this extempo (extemporaneous) melody calypsonians lyricise impromptu, commenting socially or insulting each other, "sans humanité" or "no mercy" (which is again a reference to French influence).

[8] Perhaps the most straightforward way to describe the focus of calypso is that it articulated itself as a form of protest against the authoritarian colonial culture which existed at the time.

In addition, the choral director Leonard De Paur recorded a calypso album in 1956 for Columbia Records featuring his choral arrangements of traditional Christmas music from Trinidad and Barbados, as well as the song Mary's Little Boy Child by Jester Hairston (Calypso Christmas, CL 923 Mono LP, 1956).

[10] In the Broadway-theatre musical Jamaica (1957), Harold Arlen and Yip Harburg cleverly parodied "commercial" Belafonte-style calypso.

Robert Mitchum released an album, Calypso...Is Like So (1957), on Capitol Records, capturing the sound, spirit, and subtleties of the genre.

The following year with "Come Leh We Jam", she won the "Calypso King " competition, the first time a woman had received the award.

[11][12] The French and pioneer electronic musician Jean Michel Jarre released an album in 1990 called Waiting for Cousteau.

Calypso had another short burst of commercial interest when Tim Burton's horror/comedy film Beetlejuice (1988) was released, and used Belafonte's "Jump in the Line" as the soundtrack's headliner and also "The Banana Boat Song" in the dinner-party scene.

The soca music of the 1980s featured fast tempos, electric guitars and synthesizers, prominent melodic bass lines, and lyrics celebrating sensuality and dance.

Dominicans, similar to Trinidadians also developed a keen interest in Caribbean genres such as Soca music, and Calypso in the late 1960's.

Most of the music pieces composed normally have a negative stigma attached to them, expressing dissatisfaction with how their current government choose to conduct the affairs of the country.

There is also a section called Junior monarch[4] where young children under the age of 14 are able to prepare and compete with their personally made Calypso pieces.

[17] During the colonial era, the Black lower class used calypso music to protest their poor economic situation and the discrimination which they were subjected to.

However, second version found greater popularity amongst Caribbean people themselves as the lyrics conveyed a story of West Indian immigrants facing discrimination and cultural alienation while living in Britain.