Cambrian explosion

Interpretation is difficult, owing to a limited supply of evidence based mainly on an incomplete fossil record and chemical signatures remaining in Cambrian rocks.

[18] Although their evolutionary importance was not known, on the basis of their old age, William Buckland (1784–1856) realized that a dramatic step-change in the fossil record had occurred around the base of what we now call the Cambrian.

[16] Nineteenth-century geologists such as Adam Sedgwick and Roderick Murchison used the fossils for dating rock strata, specifically for establishing the Cambrian and Silurian periods.

[17] In the sixth edition of his book, he stressed his problem further as:[20] To the question why we do not find rich fossiliferous deposits belonging to these assumed earliest periods prior to the Cambrian system, I can give no satisfactory answer.American paleontologist Charles Walcott, who studied the Burgess Shale fauna, proposed that an interval of time, the "Lipalian", was not represented in the fossil record or did not preserve fossils, and that the ancestors of the Cambrian animals evolved during this time.

Fossils (Grypania) of more complex eukaryotic cells, from which all animals, plants and fungi are built, have been found in rocks from 1,400 million years ago, in China and Montana.

[23] The intense modern interest in this "Cambrian explosion" was sparked by the work of Harry B. Whittington and colleagues, who, in the 1970s, reanalysed many fossils from the Burgess Shale and concluded that several were as complex as, but different from, any living animals.

Stephen Jay Gould's popular 1989 account of this work, Wonderful Life,[27] brought the matter into the public eye and raised questions about what the explosion represented.

While differing significantly in details, both Whittington and Gould proposed that all modern animal phyla had appeared almost simultaneously in a rather short span of geological period.

Relative dating (A was before B) is often assumed sufficient for studying processes of evolution, but this, too, has been difficult, because of the problems involved in matching up rocks of the same age across different continents.

[2] Some theory suggest Cambrian explosion occurred during the last stages of Gondwanan assembly, which is formed following Rodinia splitting, overlapped with the opening of the Iapetus Ocean between Laurentia and western Gondwana.

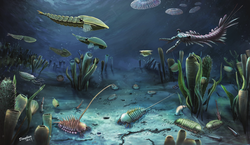

Most of the phyla featured in the debate about the Cambrian explosion[clarification needed] are coelomates: arthropods, annelid worms, molluscs, echinoderms and chordates—the noncoelomate priapulids are an important exception.

[64]At the start of the Ediacaran period, much of the acritarch fauna, which had remained relatively unchanged for hundreds of millions of years, became extinct, to be replaced with a range of new, larger species, which would prove far more ephemeral.

These are a very mixed collection of fossils: spines, sclerites (armor plates), tubes, archeocyathids (sponge-like animals) and small shells very like those of brachiopods and snail-like molluscs—but all tiny, mostly 1 to 2 mm long.

This late Early Cambrian assemblage (510 to 515 million years ago) consists of microscopic fragments of arthropods' cuticle, which is left behind when the rock is dissolved with hydrofluoric acid.

[94][95][96] Secondly, these tubes are a device to rise over a substrate and competitors for effective feeding and, to a lesser degree, they serve as armor for protection against predators and adverse conditions of environment.

Such mineral skeletons as shells, sclerites, thorns and plates appeared in uppermost Nemakit-Daldynian; they were the earliest species of halkierids, gastropods, hyoliths and other rare organisms.

The beginning of the Tommotian has historically been understood to mark an explosive increase of the number and variety of fossils of molluscs, hyoliths and sponges, along with a rich complex of skeletal elements of unknown animals, the first archaeocyathids, brachiopods, tommotiids and others.

[102] This sudden increase is partially an artefact of missing strata at the Tommotian-type section, and most of this fauna in fact began to diversify in a series of pulses through the Nemakit-Daldynian and into the Tommotian.

[104] Older (~750 Ma) fossils indicate that mineralization long preceded the Cambrian, probably defending small photosynthetic algae from single-celled eukaryotic predators.

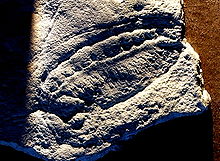

[105][106] The Burgess Shale and similar lagerstätten preserve the soft parts of organisms, which provide a wealth of data to aid in the classification of enigmatic fossils.

[108] Because the lagerstätten provide a mode and quality of preservation that is virtually absent outside of the Cambrian, many organisms appear completely different from anything known from the conventional fossil record.

The preservational mode is rare in the preceding Ediacaran period, but those assemblages known show no trace of animal life—perhaps implying a genuine absence of macroscopic metazoans.

[139] The amount of ozone (O3) required to shield Earth from biologically lethal UV radiation, wavelengths from 200 to 300 nanometers (nm), is believed to have been in existence around the Cambrian explosion.

This may have caused a mass extinction, creating a genetic bottleneck; the resulting diversification may have given rise to the Ediacara biota, which appears soon after the last "Snowball Earth" episode.

[141] However, the snowball episodes occurred a long time before the start of the Cambrian, and it is difficult to see how so much diversity could have been caused by even a series of bottlenecks;[52] the cold periods may even have delayed the evolution of large size organisms.

[62] Massive rock erosion caused by glaciers during the "Snowball Earth" may have deposited nutrient-rich sediments into the oceans, setting the stage for the Cambrian explosion.

[142] Newer research suggests that volcanically active mid-ocean ridges caused a massive and sudden surge of the calcium concentration in the oceans, making it possible for marine organisms to build skeletons and hard body parts.

Evidence of Precambrian metazoans[52] combines with molecular data[146] to show that much of the genetic architecture that could feasibly have played a role in the explosion was already well established by the Cambrian.

It is proposed that the emergence of simple multicellular forms provided a changed context and spatial scale in which novel physical processes and effects were mobilized by the products of genes that had previously evolved to serve unicellular functions.

[52] The late Ediacaran oceans appears to have suffered from an anoxia that covered much of the seafloor, which would have given mobile animals with the ability to seek out more oxygen-rich environments an advantage over sessile forms of life.

- — = Lines of descent

- = Basal node

- = Crown node

- = Total group

- = Crown group

- = Stem group