Cambridge Platform

In addition, Presbyterians did not insist upon a regenerate church membership and allowed all "non-scandalous" churchgoers to receive the Lord's Supper.

[4] In 1645, local Presbyterians led by William Vassal and Robert Child staged a protest against Massachusetts' policies on church membership and voting.

Child threatened to take his complaints to Parliament, provoking fear among colonial leaders that the English government might intervene to force Presbyterianism on New England.

[7] The synod tasked John Cotton, Richard Mather and Ralph Partridge of Duxbury to each write a model of church government for the group's consideration.

The synod unanimously voted to accept the doctrinal portions of the confession, stating that they "do judge it to be very holy, orthodox, and judicious in all matters of faith; and do therefore freely and fully consent thereunto, for the substance thereof.

The preface, written by John Cotton, counters various criticisms leveled against the New England churches and defends their orthodoxy.

[1] A Congregational church is defined as "a company of saints by calling, united into one body by a holy covenant, for the public worship of God, and the mutual edification one of another, in the fellowship of the Lord Jesus.

[16] Deacons oversee the worldly or financial affairs of the church, which include collecting contributions and gifts, paying the ministers and distributing charity to the poor.

[20] Chapter 12 stipulates that individuals seeking church membership must first undergo examination by the elders for evidence of repentance of sin and faith in Jesus Christ.

The person would then be expected to give a "relation" or public account of their conversion experience before the entire congregation prior to becoming a member.

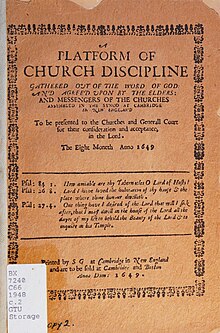

[24] The synod completed the Cambridge Platform in 1648, and after the churches were given time to study the document, provide feedback, and finally ratify it, the General Court commended it as an accurate description of Congregational practice.

While the platform was legally nonbinding and intended only to be descriptive, it soon became regarded by ministers and lay people alike as the religious constitution of Massachusetts, guaranteeing the rights of church officers and members.

[25] Congregational minister Albert Elijah Dunning wrote that it was "the most important document produced by the Congregationalists of the seventeenth century, for it most clearly represents the belief of the churches and their system of government for more than one hundred years".

[24] In Connecticut, it was replaced by the Saybrook Platform of 1708, which brought the Congregational churches closer to a presbyterian form of government.