Camel train

Despite rarely travelling faster than human walking speed, for centuries camels' ability to withstand harsh conditions made them ideal for communication and trade in the desert areas of North Africa and the Arabian Peninsula.

[1] By far the greatest use of camel trains occurs between North and West Africa by the Tuareg, Shuwa and Hassaniyya, as well as by culturally-affiliated groups like the Toubou, Hausa and Songhay.

As late as the early twentieth century, camel caravans played an important role connecting the Beijing/Shanxi region of eastern China with Mongolian centers (Urga, Uliastai, Kobdo) and Xinjiang.

In his Desert Road to Turkestan he describes mostly camel caravans run by Han Chinese and Hui firms from eastern China (Hohhot, Baotou) or Xinjiang (Qitai (then called Gucheng), Barkol), plying the routes connecting those two regions through the Gobi Desert by way of Inner (or, before Mongolia's independence, Outer) Mongolia.

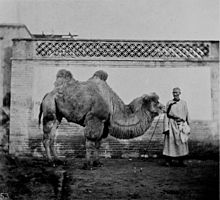

[2] Camel-pullers' salary was quite low (around 2 silver taels a month in 1926, which would not be enough even for shoes and clothing he wore out while walking with his camels), although they were also fed and provided with tent space at the caravan owner's expense.

Even more importantly, if a camel-puller could afford to buy a camel or a few of his own, he was allowed to include them into his file, and to collect the carriage-money for the cargo (assigned by the caravan owner) that they would carry.

A sheep would be bought from the Mongols and slaughtered every now and then, and tea was the usual daily drink; as fresh vegetables were scarce, scurvy was a danger.

When that was not enough (especially in winter) more fodder could be bought (very expensively) from dealers who would come to the caravan route's popular stopping places from the populated areas of Gansu or Ningxia to the south.

[12] Typical cargo carried by the caravans were commodities such as wool, cotton fabrics, or tea, as well as miscellaneous manufactured goods for sale in Xinjiang and Mongolia.

More exotic loads could include jade from Khotan,[13] elk antlers prized in Chinese medicine, or even dead bodies of the Shanxi caravan men and traders, who happened to die while in Xinjiang.

[17] Smaller caravans owned by Mongols of the Alashan (the westernmost Inner Mongolia) and manned by Han Chinese from Zhenfan, were able to make longer marches (and, thus, cover longer distances faster) than the typical Han Chinese or Hui caravans, because the Mongols were able to always use "fresh" camels (picked from their large herd for just a single journey), every man was provided with a camel to ride, and loads were much lighter than in the "standard" caravans (rarely exceeding 270 pounds (122.5 kg).

[18] Such a camel train is described in the accounts of the journey made by Peter Fleming and Ella Maillart in the Gobi Desert in the mid-1930s.

Because such long trade routes often passed through inhospitable desert regions, journeys would be impossible to complete successfully and profitably without caravanserai to provide necessary supplies and assistance to merchants and travelers.

Vice versa, one could leave Hohhot in the spring, spend the summer grazing season in Xinjiang, and come back in the late fall of the same year.

[22] Fritz Mühlenweg wrote a book called In geheimer Mission durch die Wüste Gobi (part one in English Big Tiger and Compass Mountain), published in 1950.

It was later shortened and translated into English under the title Big Tiger and Christian; it concerns the adventures of two boys who cross the Gobi Desert.