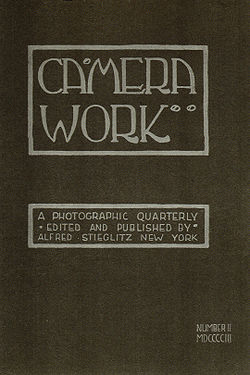

Camera Work

[5] Rather than continue to battle against these challenges, he resigned as editor of Camera Notes and spent the summer at his home in Lake George, New York, thinking about what he could do next.

[2] His close friends and fellow photographers, led by Joseph Keiley, encouraged him to carry out his dream and publish a new magazine, one that would be independent of any conservative influences.

In August, 1902, he printed a two-page prospectus, "in response to the importunities of many serious workers in photographic fields that I should undertake the publication of an independent magazine devoted to the furtherance of modern photography.

"[2] He called the new journal Camera Work, a reference to the phrase in his prospectus statement, in which he meant to distinguish artistic photographers like himself from the old-school technicians with whom he had fought for many years.

To emphasize the fact that this was an independent journal, every cover would proclaim "Camera Work: A Photographic Quarterly, Edited and Published by Alfred Stieglitz, New York".

With his typical extravagant taste and unwillingness to compromise, Stieglitz insisted that 1000 copies of every issue be printed, regardless of the number of subscriptions.

In it, Stieglitz set forth the mission of the new journal: "Photography being in the main a process in monochrome, it is on subtle gradations of tone and value that its artistic beauty so frequently depends.

Only examples of such works as gives evidence of individuality and artistic worth, regardless of school, or contains some exceptional feature of technical merit, or such as exemplifies some treatment worthy of consideration, will find recognition in these pages.

He listed them in a specific order: Robert Demachy, Will Cadby, Edward Steichen, Gertrude Käsebier, Frank Eugene, James Craig Annan, Clarence H. White, William Dyer, Eva Watson, Frances Benjamin Johnston, and R. Child Baley.

He even used the services of the same three assistant editors who worked with him on Camera Notes: Dallett Fuguet, Joseph Keiley and John Francis Strauss.

[2] One of the purposes of the new journal was to serve as a vehicle for the Photo-Secession, an invitation-only group that Stieglitz founded in 1902 to promote photography as an art form.

In 1904, Stieglitz attempted to counter this idea by publishing a full-page notice in the journal in order to correct the "erroneous impression…that only the favored few are admitted to our subscription list."

"Without the flourish of trumpets, without the stereotypes, press-view or similar antiquated functions, the Secessionists and a few friends informally opened the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession at 291 Fifth Avenue, New York.

[2] As his own successes increased, either from recognition of his own photos or through his efforts to organize international exhibitions of photography, the content of Camera Work reflected these changes.

Articles began to appear with such titles as "Symbolism and Allegory" (Charles Caffin, No 18 1907) and "The Critic as Artist" (Oscar Wilde, No 27 1909), and the focus of Camera Work turned from primarily American content to a more international scope.

[2] Stieglitz knew this signaled the end of an era, but rather than be set back by these changes he began making plans to integrate Camera Work even further into the realm of modern art.

In January, 1910, Stieglitz abandoned his policy of reproducing only photographic images, and in issue 29 he included four caricatures by Mexican artist Marius de Zayas.

From this 'point on Camera Work would include both reproductions of and articles on modern painting, drawing and aesthetics, and it marked a significant change in both the role and the nature of the magazine.

That year he changed the name of the gallery to "291", and he began showing avant-garde modern artists such as Auguste Rodin and Henri Matisse along with photographers.

The positive responses he received at the gallery encouraged Stieglitz to broaden the scope of Camera Work as well, although he decided against any name change for the journal.

More than fifteen thousand people visited the exhibition over its four-week showing, and at the end the Gallery purchased twelve prints and reserved one room for the permanent display of photography.

This was the first time a museum in the U.S. acknowledged that photography was in fact an art form, and, in many ways, it marked the beginning of the end for the Photo-Secession.

Strand shunned the soft focus and symbolic content of the Pictorialists and instead strived to create a new vision that found beauty in the clear lines and forms of ordinary objects.

Of the 473 photographs published in Camera Work during its fifteen-year existence, 357 were the work of just fourteen photographers: Stieglitz, Steichen, Frank Eugene, Clarence H. White, Alvin Langdon Coburn, J. Craig Annan, Hill & Adamson, Baron Adolf de Meyer, Heinrich Kühn, George Seeley, Paul Strand, Robert Demachy, Gertrude Käsebier and Anne Brigman.