Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot

A pivotal figure in landscape painting, his vast output simultaneously referenced the Neo-Classical tradition and anticipated the plein-air innovations of Impressionism.

His family were bourgeois people—his father was a wig maker and his mother, Marie-Françoise Corot, a milliner—and unlike the experience of some of his artistic colleagues, throughout his life he never felt the want of money, as his parents made good investments and ran their businesses well.

[11] Starting in 1822 after the death of his sister, Corot began receiving a yearly allowance of 1500 francs which adequately financed his new career, studio, materials, and travel for the rest of his life.

Highly influential upon French landscape artists in the early 19th century was the work of Englishmen John Constable and J. M. W. Turner, who reinforced the trend in favor of Realism and away from Neoclassicism.

Corot's drawing lessons included tracing lithographs, copying three-dimensional forms, and making landscape sketches and paintings outdoors, especially in the forests of Fontainebleau, the seaports along Normandy, and the villages west of Paris such as Ville-d'Avray (where his parents had a country house).

[17] With his parents' support, Corot followed the well-established pattern of French painters who went to Italy to study the masters of the Italian Renaissance and to draw the crumbling monuments of Roman antiquity.

Corot learned little from the Renaissance masters (though later he cited Leonardo da Vinci as his favorite painter) and spent most of his time around Rome and in the Italian countryside.

"[24] In spite of his strong attraction to women, he wrote of his commitment to painting: "I have only one goal in life that I want to pursue faithfully: to make landscapes.

Several of his salon paintings were adaptations of his Italian oil sketches reworked in the studio by adding imagined, formal elements consistent with Neoclassical principles.

[25] An example of this was his first Salon entry, View at Narni (1827), where he took his quick, natural study of a ruin of a Roman aqueduct in dusty bright sun and transformed it into a falsely idyllic pastoral setting with giant shade trees and green lawns, a conversion meant to appeal to the Neoclassical jurors.

While there he met the members of the Barbizon school; Théodore Rousseau, Paul Huet, Constant Troyon, Jean-François Millet, and the young Charles-François Daubigny.

[33] This time, Corot's unanticipated bold, fresh statement of the Neoclassical ideal succeeded with the critics by demonstrating "the harmony between the setting and the passion or suffering that the painter chooses to depict in it.

While recognition and acceptance by the establishment came slowly, by 1845 Baudelaire led a charge pronouncing Corot the leader in the "modern school of landscape painting".

"[36] In 1846, the French government decorated him with the cross of the Légion d'honneur and in 1848 he was awarded a second-class medal at the Salon, but he received little state patronage as a result.

"[39] Upon Delacroix's recommendation, the painter Constant Dutilleux bought a Corot painting and began a long and rewarding relationship with the artist, bringing him friendship and patrons.

A contemporary said of him, "Corot is a man of principle, unconsciously Christian; he surrenders all his freedom to his mother...he has to beg her repeatedly to get permission to go out...for dinner every other Friday.

[42] That freedom allowed him to take on students for informal sessions, including the Jewish artists Édouard Brandon and future Impressionist Camille Pissarro, who was briefly among them.

In later life, Corot's studio was filled with students, models, friends, collectors, and dealers who came and went under the tolerant eye of the master, causing him to quip, "Why is it that there are ten of you around me, and not one of you thinks to relight my pipe.

"[49] Despite great success and appreciation among artists, collectors, and the more generous critics, his many friends considered, nevertheless, that he was officially neglected, and in 1874, a short time before his death, they presented him with a gold medal.

The best known are Camille Pissarro, Eugène Boudin, Berthe Morisot, Stanislas Lépine, Antoine Chintreuil, François-Louis Français, Charles Le Roux, and Alexandre Defaux.

In his early period, he painted traditionally and "tight"—with minute exactness, clear outlines, thin brushwork, and with absolute definition of objects throughout, with a monochromatic underpainting or ébauche.

In part, this evolution in expression can be seen as marking the transition from the plein-air paintings of his youth, shot through with warm natural light, to the studio-created landscapes of his late maturity, enveloped in uniform tones of silver.

In his final 10 years he became the "Père (Father) Corot" of Parisian artistic circles, where he was regarded with personal affection, and acknowledged as one of the five or six greatest landscape painters the world had seen, along with Meindert Hobbema, Claude Lorrain, J. M. W. Turner and John Constable.

Though appearing at times to be rapid and spontaneous, usually his strokes were controlled and careful, and his compositions well-thought out and generally rendered as simply and concisely as possible, heightening the poetic effect of the imagery.

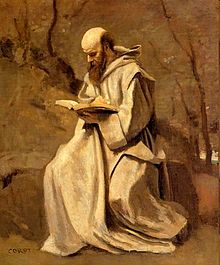

In addition to his landscapes (so popular was the late style that there exist numerous forgeries), Corot produced a number of prized figure pictures.

Like his landscapes, they are characterized by a contemplative lyricism, with his late paintings L'Algérienne (Algerian Woman) and La Jeune Grecque (The Greek Girl) being fine examples.

[61] He also painted thirteen reclining nudes, with his Les Repos (1860) strikingly similar in pose to Ingres famous Le Grande Odalisque (1814), but Corot's female is instead a rustic bacchante.

[68] According to Corot cataloguist Etienne Moreau-Nélaton, at one copying studio "The master's complacent brush authenticated these replicas with a few personal and decisive retouchings.

"[69] The cataloging of Corot's works in an attempt to separate the copies from the originals backfired when forgers used the publications as guides to expand and refine their bogus paintings.

[70] Two of Corot's works are featured and play an important role in the plot of the 2008 French film L'Heure d'été (English title Summer Hour).