Camouflage

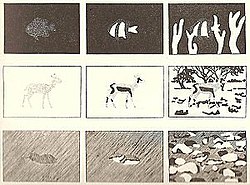

The majority of camouflage methods aim for crypsis, often through a general resemblance to the background, high contrast disruptive coloration, eliminating shadow, and countershading.

In the open ocean, where there is no background, the principal methods of camouflage are transparency, silvering, and countershading, while the ability to produce light is among other things used for counter-illumination on the undersides of cephalopods such as squid.

At sea, merchant ships and troop carriers were painted in dazzle patterns that were highly visible, but designed to confuse enemy submarines as to the target's speed, range, and heading.

According to Charles Darwin's 1859 theory of natural selection,[2] features such as camouflage evolved by providing individual animals with a reproductive advantage, enabling them to leave more offspring, on average, than other members of the same species.

[4][a] Poulton's "general protective resemblance"[6] was at that time considered to be the main method of camouflage, as when Frank Evers Beddard wrote in 1892 that "tree-frequenting animals are often green in colour.

[7] Beddard did however briefly mention other methods, including the "alluring coloration" of the flower mantis and the possibility of a different mechanism in the orange tip butterfly.

He wrote that "the scattered green spots upon the under surface of the wings might have been intended for a rough sketch of the small flowerets of the plant [an umbellifer], so close is their mutual resemblance.

"[16] Cott built on Thayer's discoveries, developing a comprehensive view of camouflage based on "maximum disruptive contrast", countershading and hundreds of examples.

The book explained how disruptive camouflage worked, using streaks of boldly contrasting colour, paradoxically making objects less visible by breaking up their outlines.

[19] Experimental evidence that camouflage helps prey avoid being detected by predators was first provided in 2016, when ground-nesting birds (plovers and coursers) were shown to survive according to how well their egg contrast matched the local environment.

[22] There is fossil evidence of camouflaged insects going back over 100 million years, for example lacewings larvae that stick debris all over their bodies much as their modern descendants do, hiding them from their prey.

However, P. melanocrachia can only feed and lay eggs on the branches of host-coral, Platygyra carnosa, which limits the geographical range and efficacy in nudibranch nutritional crypsis.

On the other hand, natural selection drives species with variable backgrounds and habitats to move symmetrical patterns away from the centre of the wing and body, disrupting their predators' symmetry recognition.

[45] Disruptive patterns use strongly contrasting, non-repeating markings such as spots or stripes to break up the outlines of an animal or military vehicle,[47] or to conceal telltale features, especially by masking the eyes, as in the common frog.

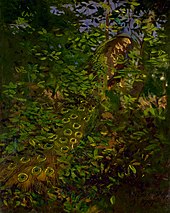

[74] Most methods of crypsis therefore also require suitable cryptic behaviour, such as lying down and keeping still to avoid being detected, or in the case of stalking predators such as the tiger, moving with extreme stealth, both slowly and quietly, watching its prey for any sign they are aware of its presence.

[106] The cephalopod chromatophore has all its pigment grains in a small elastic sac, which can be stretched or allowed to relax under the control of the brain to vary its opacity.

[111][112][113] Some animals actively seek to hide by decorating themselves with materials such as twigs, sand, or pieces of shell from their environment, to break up their outlines, to conceal the features of their bodies, and to match their backgrounds.

[117] Cott takes the example of the larva of the blotched emerald moth, which fixes a screen of fragments of leaves to its specially hooked bristles, to argue that military camouflage uses the same method, pointing out that the "device is ... essentially the same as one widely practised during the Great War for the concealment, not of caterpillars, but of caterpillar-tractors, [gun] battery positions, observation posts and so forth.

[120] Some tissues such as muscles can be made transparent, provided either they are very thin or organised as regular layers or fibrils that are small compared to the wavelength of visible light.

It involved projecting light on to the sides of ships to match the faint glow of the night sky, requiring awkward external platforms to support the lamps.

Species with this adaptation are widely dispersed in various orders of the phylogenetic tree of bony fishes (Actinopterygii), implying that natural selection has driven the convergent evolution of ultra-blackness camouflage independently many times.

[130] Vegetius (c. 360–400 AD) says that "Venetian blue" (sea green) was used in the Gallic Wars, when Julius Caesar sent his speculatoria navigia (reconnaissance boats) to gather intelligence along the coast of Britain; the ships were painted entirely in bluish-green wax, with sails, ropes and crew the same colour.

[131] There is little evidence of military use of camouflage on land before 1800, but two unusual ceramics show men in Peru's Mochica culture from before 500 AD, hunting birds with blowpipes which are fitted with a kind of shield near the mouth, perhaps to conceal the hunters' hands and faces.

[132] Another early source is a 15th-century French manuscript, The Hunting Book of Gaston Phebus, showing a horse pulling a cart which contains a hunter armed with a crossbow under a cover of branches, perhaps serving as a hide for shooting game.

[135] A contemporary study in 1800 by the English artist and soldier Charles Hamilton Smith provided evidence that grey uniforms were less visible than green ones at a range of 150 yards.

"[145] In the First World War, the French army formed a camouflage corps, led by Lucien-Victor Guirand de Scévola,[146][147] employing artists known as camoufleurs to create schemes such as tree observation posts and covers for guns.

[167] The film-maker Geoffrey Barkas ran the Middle East Command Camouflage Directorate during the 1941–1942 war in the Western Desert, including the successful deception of Operation Bertram.

Max Dupain, Sydney Ure Smith, and William Dobell were among the members of the group, which worked at Bankstown Airport, RAAF Base Richmond and Garden Island Dockyard.

It was at night, we had heard of camouflage but we had not seen it and Picasso amazed looked at it and then cried out, yes it is we who made it, that is cubism.In 1919, the attendants of a "dazzle ball", hosted by the Chelsea Arts Club, wore dazzle-patterned black and white clothing.

[193] The Illustrated London News announced:[193][194] The scheme of decoration for the great fancy dress ball given by the Chelsea Arts Club at the Albert Hall, the other day, was based on the principles of "Dazzle", the method of "camouflage" used during the war in the painting of ships ...