Canadian Indigenous law

Cree, Blackfoot, Mi'kmaq and numerous other First Nations; Inuit; and Métis will apply their own legal traditions in daily life, creating contracts, working with governmental and corporate entities, ecological management and criminal proceedings and family law.

[18] These histories include tales of Nanabozho and a wide spectrum of other beings and peoples, and the moral implications and practical applications gleaned from them.

[19] Anishinaabe Law historically has interacted with the legal systems of other nations in examples like with the Gdoo-naaganinaa (Dish With One Spoon) Treaty made with the Haudenosaunee.

[21] Arising from their homeland, Nitaskinan, the Atikamekw Nation maintains a strong connection to their language[22] and to their traditional legal system, called either irakonikewin or orakonikewin.

[23] Many differences arise between the English common law, the French civil code, and the Atikamekw irakonikewin, notably that of adoption, or opikihawasowin.

[25][26] Dene legal principles generally rest on the three foundations of equality, sharing, and reciprocity, as well as an interdependence on human and nonhuman life forces.

[26] For example, Dene law stipulates that humans travelling across country must pay for their passage in the form of gifting things to waterways, landforms, and other beings such as ancestors.

One example is the rupturing of intergenerational transmission of law due to residential schools separated children from their social (and legal) frameworks.

[29] In contrast with the paternalistic English legal system wherein humans must oversee and conserve other species, the Dene worldview stresses the agency of nonhuman beings.

[42] Gix̱san Lax̱yip, or Gitx̱san Country, maintains clear and distinct territorial jurisdictions associated with specific Huwilp, which are known and affirmed through what can be translated as treasures or inheritances, the gwalax̱ yee’nst.

[40] Although the adaawk were not accepted as testimonial evidence during the Delgamuukw-Gisday'wa case, the precedence was set such that the "admissibility [of oral histories] must be determined on a case-by-case basis".

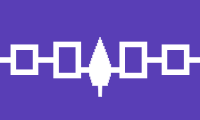

The uniting of the original five nations (the Onödowáʼga:/Seneca, the Gayogo̱hó:nǫʼ/Cayuga, the Onyota'a:ka/Oneida, the Onöñda’gaga’/Onondaga, and the Kanienʼkehá:ka/Mohawk), and thus the core legal framework, is recounted orally from the constitutional wampum, and is symbolized by the Tree of Peace, the eastern white pine.

As such, nations are conceived as elder and younger brothers, and when asked how this new structure would work, the Peacemaker replied: "It will take the form of the longhouse in which there are many hearths, one for each family, yet all live as one household under one chief mother.

Leaders and Elders do not see themselves as agents of social control or law and order, as each individual contributes to the functioning of the community.

[58][59] In contradistinction with European legal systems, Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw law understands societal structures as well as individual rights and obligations differently.

[58][59] As such, intellectual and property law differs markedly from Euro-Canadian legal systems, and conflict is still being resolved from the near-century long ban of a core institution.

[62][63] The core foundation of Métis law rests upon inherited stories, such as of Ti-Jean, Wisahkecahk, and Nanbush,[64][65][63] and ultimately centres the family, from which extend powers to the community, regional, and national levels where decisions are made by assembly.

[62][63] Justice is underlined by individual and communal rights where judicial decisions are obligated to be made in the context of a relationship of respect and trust.

[62][63] Dispute resolution hinges on being non-adversarial; decision-making is by consensus with universal suffrage with the whole community deciding on rules and limits to authority.

[62][63] Historically, the Métis legal system included a general council in charge of supervising a policing organization called la garde.

A foundation of Netukulimk is achieving adequate standards of community nutrition and economic well-being without jeopardizing the integrity, diversity, or productivity of our environment.

[67] This mindset understands the whole of life to be interconnected, describing the rights and responsibilities of the Mi’kmaq with their families, communities, nation, and eco-system.

The more appropriate term when referencing Cree––or specifically Plains Cree (nêhiyaw)––law is Wahkohtowin (ᐋᐧᐦᑰᐦᑐᐃᐧᐣ) denoting kinship and codes of conduct flowing from one's own role within the community.