Canadian women in the world wars

While Canadians were deeply divided on the issue of conscription for men, there was wide agreement that women had important new roles to play in the home, in civic life, in industry, in nursing, and even in military uniforms.

Nursing Service erected a memorial plaque at St. Andrew's Presbyterian Church (Ottawa) which is dedicated to Matron Margaret H. Smith, R.R.C.

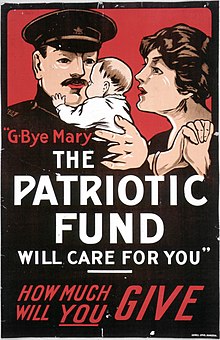

On the home front, the Canadian government was actively encouraging young men to enlist in the Royal Forces by enticing them with the promise of adventure in Europe, reminding them of their civil duty.

There was little doubt that the active service posters targeting Canadian men struck nurses more forcibly than messages pleading women to knit furiously and economize the home front.

There were other ways that women could directly serve in the war through organizations such as the St. John Ambulance Association where they could work as Voluntary Aid Detachment nurses.

During the First World War, there was virtually no female presence in the Canadian armed forces, with the exception of the 3,141 nurses serving overseas and on the home front.

These Casualty Clearing Stations, or the C.C.S., as they were titled were typically situated on a railway siding, close to the front lines so they could quickly and efficiently retrieve and treat soldiers who had fallen on the nearby battlefield.

The Casualty Clearing Stations served as an advanced surgical center that administered emergency surgeries staffed by Canada's most brilliant nurses.

1 Canadian General Hospital at Étaples, France, and the death of 14 nursing sisters and over 200 other service personnel on June 27, 1918, when HMHS Llandovery Castle was sunk by the SM U-86.

Not only did women help raise money; they rolled bandages, knitted socks, mitts, sweaters, and scarves for the men serving overseas.

Canadian women were encouraged to marshal support for the war by persuading wives and mothers to allow their men and sons to enlist.

This sacrifice included women giving up old cooking utensils and hair curlers which could be scrapped for metal and rubber to produce war materials.

As there were food shortages due to the lack of labour, canning clubs were formed to keep up with the high demand for fruits and vegetables both at home and overseas.

[28] The traditional work that Iroquois women performed during wartime was taking care of the home and children while also ensuring that their men had the necessities for war.

The diary Montour kept while serving overseas was published by her family and it “reveals that her experiences paralleled those of non-Native Canadian nurses in the war”.

As the men on campus “began conducting loud, highly visible, two-hour-long military drills” the women gathered to discuss what roles they would play during this time of war.

“U of T women also raised funds to support hospitals overseas”[33] Community dances became a popular form of fundraiser due to their lighthearted nature and offering of a place where people could forget about the war for a short amount of time.

“Wives, mothers, grandmothers, sisters, aunts, cousins, daughters, friends, girlfriends, and fiancées faced altered social, cultural, political, and economic landscapes in the wake of their loved ones’ departures.”[37] The effect that the absence of men had on women’s experiences was large as new opportunities arose.

As well, wealthy highly educated and Canadian-born white women began to question why poor, illiterate immigrant men could vote when they could not.

Many novels were written about disabled soldiers after the war by men who tended to flatten the representation of women, consigning them to one of three stereotypical roles: mothers, lovers, or nurses”.

Though women made a large impact on the wartime economy and proved that they could be both good workers and still care for their families, they would not get the recognition they deserved for a long time after the war had ended.

In a preliminary ceremony on Parliament Hill, in front of the centre block, the President of the Association, Miss Jean Browne, presented the memorial to the acting Prime Minister, Sir Henry Drayton, who accepted it in the name of the people of Canada.

[47] The finished sculpture consists of three components supporting the main theme of the heroic service of nursing sisters from the founding of Hôtel Dieu in Quebec City in 1639 to the end of the First World War.

[49] H. M. May studied the thousands entering the workforce for the first time to create famous works like Women Making Shells, a 1919 oil painting dedicated to the labour of female factory workers.

All over Canada, women responded to demands made upon them by not only selling war savings stamps and certificates but purchasing them as well, and collecting money to by bombers and mobile canteens.

Changing to the Women's Division (WD) in 1942, this unit was formed to take over positions that would allow more men to participate in combat and training duties.

"[57] Among the many jobs carried out by WD personnel, they became clerks, drivers, fabric workers, hairdressers, hospital assistants, instrument mechanics, parachute riggers, photographers, air photo interpreters, intelligence officers, instructors, weather observers, pharmacists, wireless operators, and Service Police.

[12] Women had numerous reasons for wanting to join the effort; whether they had a father, husband, or brother in the forces, or simply felt the patriotic duty to help.

"[12] Interested women were encouraged not to give up their current employment until their acceptance was confirmed by the respective military group, as they may not meet the strict entrance requirements.

"An Alberta mother of nine boys, all away at either war or factory jobs – drove the tractor, plowed the fields, put up hay, and hauled grain to the elevators, along with tending her garden, raising chickens, pigs, and turkeys, and canned hundreds of jars of fruits and vegetables.