Limbs of the horse

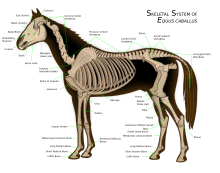

The limbs of the horse are structures made of dozens of bones, joints, muscles, tendons, and ligaments that support the weight of the equine body.

The limbs play a major part in the movement of the horse, with the legs performing the functions of absorbing impact, bearing weight, and providing thrust.

As the horse developed as a cursorial animal, with a primary defense mechanism of running over hard ground, its legs evolved to the long, sturdy, light-weight, one-toed form seen today.

Approximately 35 million years ago, a global drop in temperature created a major habitat change, leading to the transition of many forests to grasslands.

This led to a die-out among forest-dwelling equine species, eventually leaving the long-legged, one-toed Equus of today, which includes the horse, as the sole surviving genus of the Equidae family.

[7] Due to the horse's development as a cursorial animal (one whose main form of defense is running), its bones evolved to facilitate speed in a forward direction over hard ground, without the need for grasping, lifting or swinging.

The ulna shrank in size and its top portion became the point of the elbow, while the bottom fused with the radius above the radiocarpal (knee) joint, which corresponds to the wrist in humans.

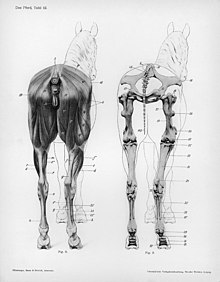

Forward motion and flexion of the hind legs is achieved through the movement of the quadriceps group of muscles on the front of the femur, while the muscles at the back of the hindquarters, called the hamstring group, provide forward motion of the body and rearward extension of the hind limbs.

The fetlock joint is supported by group of lower leg ligaments, tendons and bones known as the suspensory apparatus.

[11] Horses use a group of ligaments, tendons and muscles known as the stay apparatus to "lock" major joints in the limbs, allowing them to remain standing while relaxed or asleep.

The upper portion of the stay apparatus in the forelimbs includes the major attachment, extensor and flexor muscles and tendons.

The same portion in the hind limbs consists of the major muscles, ligaments and tendons, as well as the reciprocal joints of the hock and stifle.

The final structures are the lateral cartilages, connected to the upper coffin bone, which act as the flexible heels, allowing hoof expansion.

It acts as a support and traction point, shock absorber and system for pumping blood back through the lower limb.

During each step, with each leg, a horse completes four movements: the swing phase, the grounding or impact, the support period and the thrust.

While the horse uses muscles throughout its body to move, the legs perform the functions of absorbing impact, bearing weight, and providing thrust.

Movement adds concussive force to weight, increasing the likelihood that a poorly built leg will buckle under the strain.

[20][21] In the sport of dressage, horses are encouraged to shift their weight more to their hindquarters, which enables lightness of the forehand and increased collection.

This angle allows the hind legs to flex as weight is applied during the stride, then release as a spring to create forward or upward movement.

[23] The range of motion and propulsion power in horses varies significantly, based on the placement of muscle attachment to bone.

The legs of a horse used for cutting, in which quick starts, stops and turns are required, will be shorter and more thickly built than those of a Thoroughbred racehorse, where forward speed is most important.

Correct angles of major bones, clean, well-developed joints and tendons, and well-shaped, properly-proportioned hooves are also necessary for ideal conformation.

[25] Poor conformation and structural defects do not always cause lameness, however, as was shown by the champion racehorse Seabiscuit, who was considered undersized and knobby-kneed for a Thoroughbred.

[19] Feral horses are seldom found with serious conformation problems in the leg, as foals with these defects are generally easy prey for predators.

While horses with poor conformation and congenital conditions are more likely to develop lameness, trauma, infection and acquired abnormalities are also causes.

[29] Windpuffs, or swelling to the back of the fetlock caused by inflammation of the sheaths of the deep digital flexor tendon, appear most often in the rear legs.