Capital punishment in Russia

One of the first legal documents resembling a modern penal code was enacted in 1398, which mentioned a single capital crime: a theft performed after two prior convictions (an early precursor to the current three-strikes laws existing in several U.S. states).

The Pskov Code of 1497 extends this list significantly, mentioning three specialized theft instances (those committed in a church, stealing a horse, or, as before, with two prior "strikes"), as well as arson and treason.

The methods of execution were extremely cruel by modern standards and included drowning, burying alive, and forcing liquid metal into the throat.

[1] Elizabeth (reigned 1741–1762) did not share her father Peter's views on the death penalty, and officially suspended it in 1745, effectively enacting a moratorium.

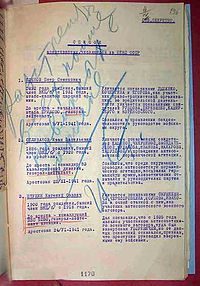

[5] The exact number of executions is debated, with archival research suggesting it to be between 700,000 and 800,000, whereas an official report to Nikita Khrushchev from 1954 cites 642,980 death penalty sentences.

[1][3] According to Western estimates, in the early 1980s Soviet courts passed around 2,000 death sentences every year, of which two-thirds were commuted to prison terms.

Consistent with this, on 25 January 1996, the Council required Russia to implement a moratorium immediately and fully abolish capital punishment within three years to approve its bid for inclusion in the organization.

[17] On 16 May 1996, President Boris Yeltsin issued a decree "for the stepwise reduction in the application of capital punishment in conjunction with Russia's entry into the Council of Europe", which is widely cited as de facto establishing such a moratorium.

[17] Although the order may be read as not legally abolishing capital punishment, this was eventually the practical effect, and it was accepted as such by the Council of Europe as Russia was granted membership in the organization.

[16] After the moratorium was announced and the maximum sentence was officially increased from 25 years to life in prison, multiple death row inmates committed suicide.

[18][19] On 2 February 1999, the Constitutional Court of Russia issued a temporary stay on any executions for a rather technical reason, but granting the moratorium an unquestionable legal status for the first time.

The court found that such disparity makes death sentences illegal in any part of the country, even those that do have the process of trial by jury implemented.

[24][25] On 9 June 2022, the Supreme Court of the Donetsk People's Republic convicted Aiden Aslin, Shaun Pinner (both British), and Brahim Saadoune (Moroccan) as mercenaries and sentenced them to the death penalty.

The Russian media and the court claimed that Aslin had confessed to "having undergone drilling aimed at carrying out terrorist acts" and that Pinner is recognised in the UK as a mercenary for partaking in the wars in Iraq and Syria.

[26] The men have said they were serving in the Ukrainian Marines, making them active-duty soldiers who should be protected by the Geneva Conventions on prisoners of war;[27] the UN and the UK condemned the verdict, supporting this claim.

This survey found that the death penalty now has a higher approval rating in urban areas (77 percent in Moscow for example), with men and among the elderly.

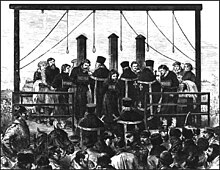

[35] Historically, various types of capital punishment were used in Russia, such as hanging, breaking wheel, burning, beheading, flagellation by knout until death, etc.

[36] In the times after Peter the Great, hanging for military men and shooting for civilians became the default means of execution,[37] though certain types of non-lethal corporal punishment, such as lashing or caning, could result in the convict's death.

That was the time typically needed for two or three appeals to be processed through the Soviet juridical system, depending on the level of the court that first sentenced the convict to death.

[citation needed] The process was usually carried out by a single executioner, usage of firing squads being limited to wartime executions.