James Cook

He served during the Seven Years' War and subsequently surveyed and mapped much of the entrance to the St. Lawrence River during the siege of Quebec, which brought him to the attention of the Admiralty and the Royal Society.

[1][3][4] In 1736, his family moved to Airey Holme farm at Great Ayton, where his father's employer, Thomas Skottowe, paid for him to attend the local school.

[7] After 18 months, not proving suited for shop work, Cook travelled to the nearby port town of Whitby to be introduced to Sanderson's friends John and Henry Walker.

As part of his apprenticeship, Cook applied himself to the study of algebra, geometry, trigonometry, navigation and astronomy – all skills he would need one day to command his own ship.

Despite the need to start back at the bottom of the naval hierarchy, Cook realised his career would advance more quickly in military service and entered the Navy at Wapping on 17 June 1755.

[15] The couple had six children: James (1763–1794), Nathaniel (1764–1780, lost aboard HMS Thunderer which foundered with all hands in a hurricane in the West Indies), Elizabeth (1767–1771), Joseph (1768–1768), George (1772–1772) and Hugh (1776–1793, who died of scarlet fever while a student at Christ's College, Cambridge).

[13][19] In June 1757, Cook formally passed his master's examinations at Trinity House, Deptford, qualifying him to navigate and handle a ship of the King's fleet.

[22][page needed] With others in Pembroke's crew, he took part in the major amphibious assault that captured the Fortress of Louisbourg from the French in 1758, and in the siege of Quebec City in 1759.

Throughout his service he demonstrated a talent for surveying and cartography and was responsible for mapping much of the entrance to the Saint Lawrence River during the siege, thus allowing General Wolfe to make his famous stealth attack during the 1759 Battle of the Plains of Abraham.

[26] They also gave Cook his mastery of practical surveying, achieved under often adverse conditions, and brought him to the attention of the Admiralty and Royal Society at a crucial moment both in his career and in the direction of British overseas discovery.

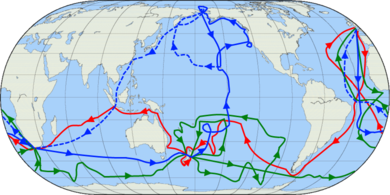

Once the observations were completed, Cook opened the sealed orders, which were additional instructions from the Admiralty for the second part of his voyage: to search the south Pacific for signs of the postulated rich southern continent of Terra Australis.

[37] Cook then voyaged west, reaching the southeastern coast of Australia near today's Point Hicks on 19 April 1770,[38][NB 1] and in doing so his expedition became the first recorded Europeans to have encountered its eastern coastline.

Cook and his crew stayed at Botany Bay for a week, collecting water, timber, fodder and botanical specimens and exploring the surrounding area.

[48] The ship was badly damaged, and his voyage was delayed almost seven weeks while repairs were carried out on the beach (near the docks of modern Cooktown, Queensland, at the mouth of the Endeavour River).

[52] Cook returned to England via Batavia (modern Jakarta, Indonesia), where many in his crew succumbed to malaria, and then the Cape of Good Hope, arriving at the island of Saint Helena on 30 April 1771.

Furneaux made his way to New Zealand, where he lost some of his men during an encounter with Māori, and eventually sailed back to Britain, while Cook continued to explore the Antarctic, reaching 71°10'S on 31 January 1774.

[61] His fame extended beyond the Admiralty; he was made a Fellow of the Royal Society and awarded the Copley Gold Medal for completing his second voyage without losing a man to scurvy.

[65] After his initial landfall in January 1778 at Waimea harbour, Kauai, Cook named the archipelago the "Sandwich Islands" after the fourth Earl of Sandwich—the acting First Lord of the Admiralty.

[66] In a single visit, Cook charted the majority of the North American northwest coastline on world maps for the first time, determined the extent of Alaska, and closed the gaps in Russian (from the west) and Spanish (from the south) exploratory probes of the northern limits of the Pacific.

[69] He became increasingly frustrated on this voyage and perhaps began to suffer from a stomach ailment; it has been speculated that this led to irrational behaviour towards his crew, such as forcing them to eat walrus meat, which they had pronounced inedible.

The body was disembowelled and baked to facilitate removal of the flesh, and the bones were carefully cleaned for preservation as religious icons in a fashion somewhat reminiscent of the treatment of European saints in the Middle Ages.

In this year John Mackrell, the great-nephew of Isaac Smith, Elizabeth Cook's cousin, organised the display of this collection at the request of the NSW Government at the Colonial and Indian Exhibition in London.

[citation needed] Cook gathered accurate longitude measurements during his first voyage from his navigational skills, with the help of astronomer Charles Green, and by using the newly published Nautical Almanac tables, via the lunar distance method – measuring the angular distance from the Moon to either the Sun during daytime or one of eight bright stars during night-time to determine the time at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich, and comparing that to his local time determined via the altitude of the Sun, Moon, or stars.

[citation needed] On his second voyage, Cook used the K1 chronometer made by Larcum Kendall, which was the shape of a large pocket watch, 5 inches (13 cm) in diameter.

In 1779, while the American colonies were fighting Britain for their independence, Benjamin Franklin wrote to captains of colonial warships at sea, recommending that if they came into contact with Cook's vessel, they were to "not consider her an enemy, nor suffer any plunder to be made of the effects contained in her, nor obstruct her immediate return to England by detaining her or sending her into any other part of Europe or to America; but that you treat the said Captain Cook and his people with all civility and kindness ... as common friends to mankind.

[111] Cooks' Cottage, his parents' last home, which he is likely to have visited, is now in Melbourne, Australia, having been moved from England at the behest of the Australian philanthropist Sir Russell Grimwade in 1934.

[122] Tributes also abound in post-industrial Middlesbrough, including a primary school,[123] shopping square[124] and the Bottle 'O Notes, a public artwork by Claes Oldenburg, that was erected in the town's Central Gardens in 1993.

Maddock states that Cook is usually portrayed as the bringer of Western colonialism to Australia and is presented as a villain who brings immense social change.

Several countries, including Australia and New Zealand, arranged official events to commemorate the voyage,[137][138] leading to widespread public debate about Cook's legacy and the violence associated with his contacts with Indigenous peoples.

[139][140] In the lead-up to the commemorations, various memorials to Cook in Australia and New Zealand were vandalised, and there were public calls for their removal or modification due to their alleged promotion of colonialist narratives.