Capture of Saint Vincent

British Governor Valentine Morris and military commander Lieutenant Colonel George Etherington disagreed on how to react and ended up surrendering without significant resistance.

[6] Furthermore, Byron departed St. Lucia on 6 June in order to provide escort services to British merchant ships gathering at St. Kitts for a convoy to Europe, leaving d'Estaing free to act.

D'Estaing and the governor, François Claude Amour, marquis de Bouillé, seized the opportunity to begin a series of operations against nearby British possessions.

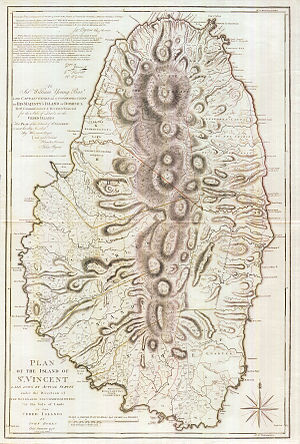

The line dividing these territories ran from the island's north-west to its south-east, and had been agreed in a treaty signed in 1773 after the First Carib War.

[10] The French capture of Dominica in 1778 had raised constitutional questions surrounding the imposition of martial law, and the colonial assembly had consequently refused to appropriate funds for improving the island defences.

[11] The only British military presence on the island was a garrison of about 450 men from the Royal American Regiment under the command of Lieutenant Colonel George Etherington, most of whom were poorly trained recruits and about half of whom were unfit for duty.

Local planters who thought they might be merchant vessels expected to pick up the sugar harvest prevented a sentry at one of the island's coastal fortifications from firing a signal cannon, and one man sent out to one of the ships was taken prisoner.

[22] The alarm was eventually raised, and Governor Morris thought it would be possible to make a stand against the French in the hills above Kingstown, in hopes that the Royal Navy would bring relief.

[23] After du Rumain's success, d'Estaing sailed with his entire fleet for Barbados at the end of June, but was unable to make significant progress against the prevailing winds.

Admiral Byron had been alerted to the capture of Saint Vincent on 1 July, and was preparing a force to retake it when he learnt of the attack on Grenada.

[25] Both Grenada and Saint Vincent remained in French hands until the end of the war, when they were returned to Britain under the terms of the 1783 Treaty of Paris.

Arriving in the Caribbean after one of the worst hurricane seasons on record, Rodney acted on rumours that Saint Vincent's defences had been devastated by an October hurricane that wrought havoc throughout the West Indies,[27][28] and sailed to Saint Vincent with ten ships of the line and 250 soldiers under General John Vaughan.

[32] Governor Morris, a long-time resident of the island, demanded an inquiry into his behaviour, alleging it had been misrepresented in the press and other writings; he was also vindicated.