Zettelkasten

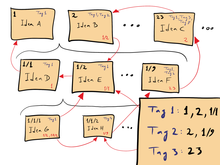

[5] As used in research, study, and writing, a card file consists of many individual notes with ideas and other short pieces of information that are taken down as they occur or are acquired.

In retrospect, his recommendation of gluing slips onto bound sheets[12] was an innovation in moving from commonplace books to index cards as a form factor for scholarly information management.

Harrison's manuscript on the "ark of studies"[15] (Arca studiorum) describes a small cabinet that allows users to excerpt books and file their notes in a specific order by attaching pieces of paper to metal hooks labeled by subject headings.

[18] Over 1,000 of Linnaeus's precursors to the modern index card containing information collected from books and other publications and measuring five by three inches are housed at the Linnean Society of London.

[16] Later in his own commonplace, under the heading "My way of collecting materials for future writings" (translated), Johann Jacob Moser (1701–1785) described the algorithms with which he filled his card boxes.

[7] The 1796 idyll Leben des Quintus Fixlein by German Romantic writer Jean Paul is structured according to the Zettelkasten in which the protagonist keeps his autobiography.

For the details of this he refers the reader to Organization of Intellectual Work: Practical Recipes for Use by Students of All Faculties and Workers (1918) by Paul Chavigny [fr].

[32] A German-language manual on research methods that included instructions for a Zettelkasten was Technique of Scholarly Work (multiple editions from the 1930s to 1970) by Johannes Erich Heyde [de].

[20] In the creation of the Great Books of the Western World (1952), which also includes A Syntopicon, Mortimer J. Adler and many collaborators created a large shared collection of tagged and indexed cards to collate the ideas and information for their series.

[43] Argentine-Canadian philosopher and physicist Mario Bunge (1919–2020), who published about 70 books and 540 articles,[44] used index cards in boxes to teach and to write publications starting in the mid-1950s.

Starting in 1952–1953, Luhmann built up a Zettelkasten of some 90,000 index cards for his research, and credited it for enabling his extraordinarily prolific writing (including about 50 books and 550 articles).

[48] Other well known German Zettelkasten users include Arno Schmidt (who used a large card file to write Zettels Traum, published in 1970), Walter Kempowski, Friedrich Kittler, and Aby Warburg, whose works along with those of Paul, Blumenberg, and Luhmann appeared in the 2013 exhibition "Zettelkästen.