Carinthian Slovenes

[citation needed] Finally, Bavarian settlers moved into Carinthia, where they established themselves in the hitherto sparsely populated areas, such as wooded regions and high valleys.

[1] The local capital Klagenfurt, at this time a bilingual city with social superior German usage and Slovene-speaking environs, was also a centre of Slovene culture and literature.

With the emergence of the nationalist movement in the late Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, there was an acceleration in the process of assimilation; at the same time the conflict between national groups became more intense.

These conciliatory promises, in addition to economic and other reasons, led to about 40% of the Slovenes living in the plebiscite zone voting to retain the unity of Carinthia.

Similar to other European states, German nationalism in Austria grew in the interwar period and ethnic tensions led to an increasing discrimination against Carinthian Slovenes.

The persecution increased with the 1938 Anschluss and escalated in 1942, when Slovene families were systematically expelled from their farms and homes and many were also sent to Nazi concentration camps, such as Ravensbrück, where the multiple-awarded writer Maja Haderlap's Grandmother was sent to.

Families whose members were fighting against Nazis as resistance fighters, were treated as 'homeland traitors' by the Austrian German-speaking neighbors, as described by Maja Haderlap,[2] after the WWII when they were forced by the British to withdraw from Austria.

As the Nazi rule had strongy reinforced the stigmatization of Slovene language and culture, anti-Slovene sentiments continued after WWII amongst large swaths of the German-speaking population in Carinthia.

In 1957, the German national Kärntner Heimatdienst (KHD) pressure group was established, by its own admission in order to advocate the interests of "patriotic" Carinthians.

Since the 1990s, a growing interest in Slovene on the part of the German-speaking Carinthians has been perceptible, but this could turn out to be too late in view of the increase in the proportion of elderly people.

However, the success of Jörg Haider, former governor of Carinthia from 1999 to 2008, in making again a political issue out of the dispute over bilingual place-name signs showed that the conflict is, as before, still present.

[citation needed] At the end of the 19th century, Carinthian Slovenes comprised approximately one quarter to one third of the total population of Carinthia, which then, however, included parts that in the meantime have been ceded.

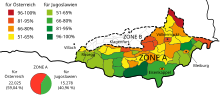

As the pressure from German came above all from the west and north, the present area of settlement lies in the south and east of the state, in the valleys known in German as Jauntal (Slovene: Podjuna), Rosental (Slovene: Rož), the lower Lavanttal (Labotska dolina), the Sattniz (Gure) mountains between the Drau River and Klagenfurt, and the lower part of Gailtal / Ziljska dolina (to about as far as Tröpolach).

The municipalities with the highest proportion of Carinthian Slovenes are Zell (89%), Globasnitz (42%), and Eisenkappel-Vellach (38%), according to the 2001 special census which inquired about the mother tongue and preferred language.

The historic description Windisch was applied in the German-speaking area to all Slavic languages (confer Wends in Germania Slavica) and in particular to the Slovene spoken in southern Austria until the 19th century.

It was perpetuated by Primož Trubar's Catechismus in der windischen Sprach, the first printed book in Slovene published in 1550, and still common during the Protestant Reformation, as noted by scholar Jernej Kopitar (1780–1844).

Gustav Januš and Andrej Kokot, as well as those lyric poets not currently writing, namely Erik Prunč and Karel Smolle, form the next generation.

A group including Janko Ferk, Maja Haderlap, Franc Merkac, Jani Oswald, Vincenc Gotthardt, Fabjan Hafner and Cvetka Lipuš that formed itself predominantly around the literary periodical Mladje (Youth) follows these lyric poets.

[7] On 3 October 1945, a new law on schools that envisaged a bilingual education for all children in the traditional area of settlement of the Carinthian Slovenes, regardless of the ethnic group to which they belonged, was passed.

After the signing of the State Treaty in 1955 and the solution of the hitherto open question of the course of the Austrian–Yugoslav border that was implicitly associated with this, there were protests against this model, culminating in 1958 in a school strike.

As a result of this development, the state governor (Landeshauptmann), Ferdinand Wedenig, issued a decree in September 1958 that made it possible for parents or guardians to deregister their children from bilingual teaching.

[6] As a result of what in effect was an associated compulsion to declare one's allegiance to an ethnic minority, the numbers of pupils in the bilingual system sank considerably.

[6] As a result of a private initiative, the Slovene music school (Kärntner Musikschule/Glasbena šola na Koroškem) was founded in 1984 and has received public funds since 1998 when a co-operation agreement was concluded with the State of Carinthia.

The prize has been awarded to, among others, the industrialist Herbert Liaunig, the governor of South Tyrol Luis Durnwalder, and professor of general and diachronic linguistics at the University of Klagenfurt Heinz Dieter Pohl, scholar and professor at the Central European University Anton Pelinka Roman Catholic prelate Egon Kapellari, Austrian politician Rudolf Kirchschläger and others.