Carlos Mesa

Carlos Diego de Mesa Gisbert[b] (Spanish pronunciation: [ˈkaɾlos ˈðjeɣo ˈmesa xisˈβeɾt] ⓘ; born 12 August 1953) is a Bolivian historian, journalist, and politician who served as the 63rd president of Bolivia from 2003 to 2005.

The Sánchez de Lozada-Mesa ticket won the election, and, on 6 August, Mesa took charge of a largely ceremonial office that carried with it few formal powers save for guaranteeing the constitutional line of succession.

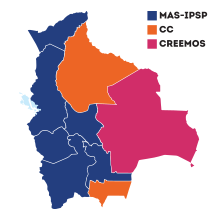

The following year, snap elections were held, but numerous postponements and an unpopular transitional government hampered Mesa's campaign, resulting in a first-round loss to Movement for Socialism (MAS) candidate Luis Arce.

[15] Save for the eventual removal of prerecorded questions, which Mesa stated "broke the continuity of the program, and also limited the topic of the conversation to excessively circumstantial issues", the style and presentation of De Cerca remained largely unchanged for two decades and between four channels, lending it a sense of "permanence in time".

Mesa's suspicions that the subject of the survey would regard political candidates were confirmed when two consultants—Jeremy Rosner and Amy Webber—met him at his office at PAT, presenting the journalist with results showing him with the highest favorability among a list of a dozen national figures.

[26] The MNR closed its Extraordinary National Convention on 3 February with the announcement of Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada as the party's presidential candidate, accompanied by Carlos Mesa as his non-partisan running mate.

[27] At first glance, election day on 30 June yielded an electoral victory for the Sánchez de Lozada-Mesa ticket amid a well-conducted and orderly process, generally accepted by the contending parties and their supporters.

Second and third place, respectively, went to the Movement for Socialism (MAS-IPSP) of the indigenous cocalero activist Evo Morales and the New Republican Force (NFR) of Cochabamba Mayor Manfred Reyes Villa; each of them took a twenty percent share of the vote.

[28] The blow to the country's traditional party system resulted in a tense runoff in which Sánchez de Lozada was forced to form an unlikely coalition with Paz Zamora in order to shore up a majority of congressional support.

Sánchez de Lozada, whom Mesa describes as "the most stubborn man I have ever met", remained steadfast in his refusal to give in to social demands, causing the vice president to snap at him that "the dead are going to bury you".

Congress had left several vacancies due to its inability to nominate judges who could gain the support of two-thirds of the legislators, causing delays in the judicial system because the Court could not reach the majorities necessary to adopt rulings.

[81][82] The latter decision was the basis for the traditional parties' objection to the plebiscite; the MIR, ADN, and sectors of the MNR, among other criticisms, voiced their opinion that the convocation of the referendum through any form other than a law passed by the legislature was illegal.

[83] Simultaneously, the five questions, drafted by both Mesa and MAS representatives,[e] caused a divide in the labor and social movements because they did not directly address the nationalization of gas reserves, an action supported by over eighty percent of the country.

As a result, Mesa announced on 20 August that he would not enact any legislation authorized by Congress until an agreement was reached, a pledge he was forced to retract two days later amid criticism that he was jeopardizing the convocation of municipal elections.

On 20 October, faced with immense external pressure from over 15,000 peasant protesters arriving from Caracollo, Congress discarded the president's bill and agreed to move forward with the one proposed by the Mixed Commission for Economic Development, headed by Santos Ramírez of the MAS.

[97] In a forty-five-minute speech broadcast on radio and television, Mesa put to use his oratory skills, denouncing both left-wing labor sectors as well as conservative autonomists and business elites and directly calling out Evo Morales by name.

In exchange, the legislature committed to a four-point agenda: expedite the drafting of the hydrocarbons bill; begin the process of approving an autonomy referendum, the democratic election of prefects, and the convocation of a constituent assembly; construct a national "social pact"; and initiate efforts to end the ongoing blockades.

He outlined his government's intent to address the matter through the convocation of a constituent assembly that would amend the relevant articles in the Constitution in order to provide for the decentralization of the country and the election of prefects and departmental councilors by popular vote.

[126] On 15 April 2004, Mesa authorized an agreement with Argentine President Néstor Kirchner allowing for the sale of four million cubic meters daily of Bolivian gas for a six-month period with the possibility of renewal depending on the outcome of the July referendum.

[127] The arrangement was supported by civic groups in Tarija—home to eighty-five percent of the country's natural gas—but was met with suspicion by certain labor sectors who viewed it as a possible roundabout way for Bolivian gas to be exported to Chile through Argentina.

Later that month, at a seven-hour session of parliament, Congress declared the maritime claim to be an "inalienable right of the Bolivian people" and issued its approval for Mesa's strategy of multilateralizing the demand in order to gain support from as many nations as possible.

[135][136] At the 34th General Assembly of the Organization of American States held in Quito, Ecuador, the Bolivian delegation distributed its Libro Azul, which recounted the government's interpretation of events surrounding the War of the Pacific and justifies the country's historical claim.

[137] At a meeting in Lima held on 4 November 2003, Mesa and Peruvian President Alejandro Toledo agreed on the framework for a common market between the two states in order to support greater cultural, commercial, and economic integration as advocated by the Andean Community.

[157][158] The decision to appoint Mesa did not come as a surprise; several politicians in past weeks, including President of the Chamber of Deputies Marcelo Elío Chávez, had suggested his inclusion on the DIREMAR team due to his historical expertise.

At the same time, he remained harshly critical of the government's undemocratic tendencies, and the ruling party filed various legal complaints against him, the most notable being the Quiborax case in which he was accused of breach of duties for actions taken during his presidency.

[173] In an interview with Erbol on 19 September, Mesa declared that he would not make any political statements or comment on his potential candidacy "as long as the issue of the sea is the fundamental question", committing himself entirely to his duties until the ruling by The Hague on 1 October.

[193] Shortly after, however, he expressed concern that the government's official live count had paralyzed at 27.14 percent and called for civic mobilizations and opposition demonstrations before the TSE and its departmental branches to avoid suspected fraud.

During extra-legislative meetings held to discuss a solution to the serious issues facing the country, then-president of the Senate Adriana Salvatierra, anticipating the possible resignation of Morales, raised her claim to constitutional succession and asked if the opposition would accept it.

[207] On 3 February, a total of seven opposition fronts were registered for the new elections, including Mesa's Civic Community as well as Áñez's Juntos alliance, Luis Fernando Camacho's Creemos, and Libre21 of Jorge Quiroga, among other minor parties.

[226][227] Together with Juan Carlos Enríquez, Ramiro Molina Barrios, and Marcos Loayza, he produced Planeta Bolivia, a series of five documentaries covering crucial environmental challenges facing the country in the twenty-first century.