Carolingian dynasty

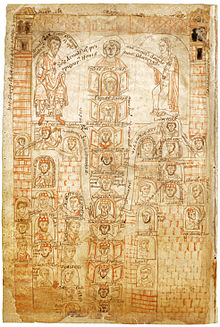

The Carolingian dynasty (/ˌkærəˈlɪndʒiən/ KARR-ə-LIN-jee-ən;[1] known variously as the Carlovingians, Carolingus, Carolings, Karolinger or Karlings) was a Frankish noble family named after Charles Martel and his grandson Charlemagne, descendants of the Arnulfing and Pippinid clans of the 7th century AD.

'[7] The reason Pippin was not rewarded sooner is not certain, but two mayors, Rado (613 – c. 617) and Chucus (c. 617 – c. 624), are believed to have preceded him and were potentially political rivals connected to the fellow Austrasian 'Gundoinings' noble family.

As a result, Pippin lost his position as mayor and the support of the Austrasian magnates, who were seemingly irritated by his inability to persuade the King to return the political centre to Austrasia.

Pippin's daughter Gertrude and wife Itta founded and entered the Nivelles Abbey, and his only son Grimoald worked to secure his father's position of maior palatii.

The Continuations offers a famous description of Sigibert being 'seized with the wildest grief and sat there on his horse weeping unrestrainedly for those he had lost' as Radulf returned to his camp victorious.

He utilized the existing links between the family and ecclesiastical community to gain control over local holy men and women who, in turn, supported Pippinid assertions of power.

[7] Grimoald and Childebert's deaths brought an end to the direct Pippinid line of the family, leaving the Arnulfing descendants from Begga and Ansegisel to continue the faction.

This story is regarded as slightly fantastical by Paul Fouracre, who argues the AMP, a pro-Carolingian source potentially written by Giselle (Charlemagne's sister) in 805 at Chelles, is that Pippin's role primes him perfectly for his future and demonstrates his family to be 'natural leaders of Austrasia.

[6] His son Drogo, from his wife Plectrude, was also imbued with power when he married Berchar's widow Adaltrude (potentially maneuvered by Ansfled) and was made Duke of Champagne.

[7] Imbued with internal strength, Pippin also began to look outwards from the Frankish Empire to subdue the people, that the AMP records, who once were 'subjected to the Franks ... [such as] the Saxons, Frisians, Alemans, Bavarians, Aquitainians, Gascons and Britons.

'[13] Pippin defeated the pagan chieftain Radbod in Frisia, an area that had been slowly encroached upon by Austrasian nobles and Anglo-Saxon missionaries like Willibrord, whose links would later make him a connection between the Arnulfings and the papacy.

Theudoald and the Arnulfings' supporters met at the Battle of Compiègne on 26 September 715,[7] and after a decisive victory, the Neustrians installed a new mayor Ragenfrid and, following Dagobert's death, their own Merovingian king Chilperic II.

[9][13] Chilperic, Raganfred and, according to the Continuations, Radbod, then travelled from Neustria through the forest of the Ardennes and raided around the river Rhine and Cologne, taking treasure from Plectrude and her supporters.

In 718, the AMP records that Charles fought against the Saxons, pushing them as far as the river Weser[13] and following up with subsequent campaigns in 720 and 724 which secured the northern borders of Austrasia and Neustria.

The region had almost gained independence during the reign of Pippin II and under the leadership of Lantfrid, Duke of Alemannia, as (710–730) they acted without Frankish authority, issuing law codes like the Lex Alamannorum without Carolingian consultation.

[7] As successful as campaigning had been, Charles seemingly took inspiration from Anglo-Saxon missionary Saint Boniface, who in 719 was sent by Pope Gregory II to convert Germany, in particular the areas of Thuringia and Hesse, where he established the monasteries of Ohrdruf, Tauberbischofsheim, Kitzingen and Ochsenfurt.

Like Alemannia, Bavaria had continued to gain independence under the rule of the Agilolfings clan who, in recent years, had increased links with Lombardy and affirmed their own law codes, like the Lex Baiuvariorum.

Following Abd al-Rahman's ascension in Spain in 731, another local Berber lord Munuza revolted, set himself up at Cerdanya and forged defensive alliances with the Franks and Aquitainians through a marriage to Eudo's daughter.

Abd ar-Rahman then besieged Cerdanya and forced Munuza into retreat into France, at which point he continued his advance into Aquitaine, moving as far as Tours before he was met by Charles Martel.

Bede, writing at the same time in Jarrow, England, recorded the event in his Ecclesiastical History of the English People, and his victory gained Charles Martel the admiration of seminal historian Edward Gibbon who considered him the Christian saviour of Europe.

Influential nobility like Savaric of Auxerre, who had maintained near-autonomy and led military forces against Burgundian towns like Orléans, Nevers and Troyes, even dying whilst besieging Lyon, were the key to Charles' support.

[24] In 739, he used his power in Burgundy and Aquitaine to lead an attack with his brother Childebrand I against Arab invaders and Duke Maurontus, who had been claiming independence and allying himself with Muslim emir Abd ar-Rahman.

In 19th century historiography, historians like Heinrich Brunner even centred their arguments around Charles' necessity for military resources, in particular the development of mounted warrior or cavalry that would peak in the High Middle Ages.

Ganshof's arguments connect these ties to a military-tenure relationship; however, this is never represented in primary material, and instead is only implied, and likely derived from, an understanding of 'feudalism' in the High Middle Ages.

Recent historians like Paul Fouracre have criticised Ganshof's review for being too simplistic, and in reality, even though these systems of vassalage did exist between lord and populace, they were not as standardised as older historiography has suggested.

For example, Fouracre has drawn particular attention to the incentives that drew lords and warriors into the Carolingian armies, arguing that the primary draw was 'booty' and treasure gained from conquest rather than 'feudal' obligation.

Due to Charles' continued military and missionary work, the political systems that existed in the heartlands, Austrasia and Neustria, officially began to spread to the periphery.

[41] The Carolingians differed markedly from the Merovingians in that they disallowed inheritance to illegitimate offspring, possibly in an effort to prevent infighting among heirs and assure a limit to the division of the realm.

One chronicler of Sens dates the end of Carolingian rule with the coronation of Robert II of France as junior co-ruler with his father, Hugh Capet, thus beginning the Capetian dynasty.

Beginning with Pippin II, the Carolingians set out to put the regnum Francorum ("kingdom of the Franks") back together, after its fragmentation after the death of Dagobert I, a Merovingian king.