Cartridge (firearms)

Prior to its invention, the projectiles and propellant were carried separately and had to be individually loaded via the muzzle into the gun barrel before firing, then have a separate ignitor compound (from a burning slow match, to a small charge of gunpowder in a flash pan, to a metallic percussion cap mounted on top of a "nipple" or cone), to serve as a source of activation energy to set off the shot.

Such loading procedures often require adding paper/cloth wadding and ramming down repeatedly with a rod to optimize the gas seal, and are thus clumsy and inconvenient, severely restricting the practical rate of fire of the weapon, leaving the shooter vulnerable to the threat of close combat (particularly cavalry charges) as well as complicating the logistics of ammunition.

The primary purpose of using a cartridge is to offer a handy pre-assembled "all-in-one" package that is convenient to handle and transport, easily loaded into the breech (rear end) of the barrel, as well as preventing potential propellant loss, contamination or degradation from moisture and the elements.

The shock-sensitive chemical in the primer then creates a jet of sparks that travels into the case and ignites the main propellant charge within, causing the powders to deflagrate (but not detonate).

After the bullet exits the barrel, the gases are released to the surroundings as ejectae in a loud blast, and the chamber pressure drops back down to ambient level.

A ghost shoulder, rather than a continuous taper on the case wall, helps the cartridge to line up concentrically with the bore axis, contributing to accuracy.

Constituents of these gases condense on the (relatively cold) chamber wall, and this solid propellant residue can make extraction of fired cases difficult.

For smoothbore weapons such as shotguns, small metallic balls known as shots are typically used, which is usually contained inside a semi-flexible, cup-like sabot called "wadding".

When fired, the wadding is launched from the gun as a payload-carrying projectile, loosens and opens itself up after exiting the barrel, and then inertially releases the contained shots as a hail of sub-projectiles.

These combustion gases become highly pressurized in a confined space—such as the cartridge casing (reinforced by the chamber wall) occluded from the front by the projectile (bullet, or wadding containing shots/slug) and from behind by the primer (supported by the bolt/breechblock).

Because the main propellant charge are located deep inside the gun barrel and thus impractical to be directly lighted from the outside, an intermediate is needed to relay the ignition.

In the earliest black powder muzzleloaders, a fuse was used to direct a small flame through a touch hole into the barrel, which was slow and subjected to disturbance from environmental conditions.

The disadvantage Is that the flash pan cAN still be exposed to the outside, making it difficult (or even impossible) to fire the gun in rainy or humid conditions as wet gunpowder burns poorly.

After Edward Charles Howard discovered fulminates in 1800[9][10] and the patent by Reverend Alexander John Forsyth expired in 1807,[11] Joseph Manton invented the precursor percussion cap in 1814,[12] which was further developed in 1822 by the English-born American artist Joshua Shaw,[13] and caplock fowling pieces appeared in Regency era England.

In rimfire ammunitions, the primer compound is moulded integrally into the interior of the protruding case rim, which is crushed between the firing pin and the edge of the barrel breech (serving as the "anvil").

Firing a fresh cartridge behind a squib load obstructing the barrel will generate dangerously high pressure, leading to a catastrophic failure and potentially causing severe injuries when the gun blows apart in the shooter's hands.

[14] Critical cartridge specifications include neck size, bullet weight and caliber, maximum pressure, headspace, overall length, case body diameter and taper, shoulder design, rim type, etc.

The evolving nature of warfare required a firearm that could load and fire more rapidly, resulting in the flintlock musket (and later the Baker rifle), in which the pan was covered by furrowed steel.

[29] Later developments rendered this method of priming unnecessary, as, in loading, a portion of the charge of powder passed from the barrel through the vent into the pan, where it was held by the cover and hammer.

This was only generally applied to the British military musket (the Brown Bess) in 1842, a quarter of a century after the invention of percussion powder and after an elaborate government test at Woolwich in 1834.

[citation needed] However, this big leap forward came at a price: it introduced an extra component into each round – the cartridge case – which had to be removed before the gun could be reloaded.

The mechanism of a modern gun must not only load and fire the piece but also provide a method of removing the spent case, which might require just as many added moving parts.

This invention has completely revolutionized the art of gun making, has been successfully applied to all descriptions of firearms and has produced a new and important industry: that of cartridge manufacture.

A small percussion cap was placed in the middle of the base of the cartridge and was ignited by means of a brass pin projecting from the side and struck by the hammer.

[47][48] In 1867, the British war office adopted the Eley–Boxer metallic centerfire cartridge case in the Pattern 1853 Enfield rifles, which were converted to Snider-Enfield breech-loaders on the Snider principle.

[citation needed] Centerfire cartridges with solid-drawn metallic cases containing their own means of ignition are almost universally used in all modern varieties of military and sporting rifles and pistols.

All such cartridges' headspace on the case mouth (although some, such as .38 Super, at one time seated on the rim, this was changed for accuracy reasons), which prevents the round from entering too far into the chamber.

Many governments and companies continue to develop caseless ammunition [citation needed] (where the entire case assembly is either consumed when the round fires or whatever remains is ejected with the bullet).

The direct electrical firing eliminates the mechanical delays associated with a striker, reducing lock time and allowing for easier adjustment of the rifle trigger.

[citation needed] The brightly colored ECI is an inert cartridge base designed to prevent a live round from being unintentionally chambered, to reduce the chances of an accidental discharge from mechanical or operator failure.

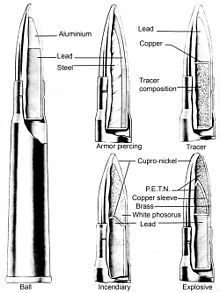

1. Bullet , as the projectile ;

2. Cartridge case , which holds all parts together;

3. Propellant , for example, gunpowder or cordite ;

4. Rim , which provides the extractor on the firearm a place to grip the casing to remove it from the chamber once fired;

5. Primer , which ignites the propellant

( 1 ) Colt Army 1860 .44 paper cartridge, Civil War

( 2 ) Colt Thuer-Conversion .44 revolver cartridge, patented in 1868

( 3 ) .44 Henry rim fire cartridge flat

( 4 ) .44 Henry rim fire cartridge pointed

( 5 ) Frankford Arsenal .45 Colt cartridge, Benét ignition

( 6 ) Frankford Arsenal .45 Colt-Schofield cartridge, Benét ignition

- 7.62×51mm NATO (left)

- 9×19mm Parabellum (right).