Castell Coch

Abandoned shortly afterwards, the castle's earth motte was reused by Gilbert de Clare as the basis for a new stone fortification, which he built between 1267 and 1277 to control his freshly annexed Welsh lands.

In 1760, the castle ruins were acquired by John Stuart, 3rd Earl of Bute, as part of a marriage settlement that brought the family vast estates in South Wales.

One of Britain's wealthiest men, with interests in architecture and antiquarian studies, he employed the architect William Burges to rebuild the castle, "as a country residence for occasional occupation in the summer", using the medieval remains as a basis for the design.

[1] The exterior, based on 19th-century studies by the antiquarian George Thomas Clark, is relatively authentic in style, although its three stone towers were adapted by Burges to present a dramatic silhouette, closer in design to mainland European castles such as Chillon than native British fortifications.

[2] The surrounding Castell Coch beech woods contain rare plant species and unusual geological features and are protected as a Site of Special Scientific Interest.

[14] The artist and illustrator Julius Caesar Ibbetson painted the castle in 1792, depicting substantial remains and a prominent tower, with a lime kiln in operation alongside the fortification.

[18] A similar view was sketched by an unknown artist in the early 19th century, showing more trees around the ruins; a few years later, Robert Drane recommended the site as a place for picnics and noted its abundance of wild garlic.

[26] Interest in medieval architecture increased in Britain during the 19th century, and in 1850 the antiquarian George Thomas Clark surveyed Castell Coch and published his findings, the first major scholarly work about the castle.

[30][31] Burges's lavishly illustrated report, which drew extensively on Clark's earlier work, laid out two options: either conserve the ruins or rebuild the castle to create a house for occasional occupation in the summer.

The result closely followed Burges's original plans, with the exception of an additional watch tower intended to resemble a minaret, and some defensive timber hoardings, both of which were not undertaken.

[33][37][40] Clark continued to advise Burges on historical aspects of the reconstruction and the architect tested the details of proposed features, such as the drawbridge and portcullis, against surviving designs at other British castles.

[1][53] Bute and his wife Gwendolen were consulted over the details of the interior decoration; replica family portraits based on those at Cardiff were commissioned to hang on the walls.

[61] Bute died in 1900 and his widow, the Marchioness, was given a life interest in Castell Coch; during her mourning, she and her daughter, Lady Margaret Crichton-Stuart, occupied the castle and made occasional visits thereafter.

[74] The castle has been used as a location for films and television programmes, including The Black Knight (1954), Sword of the Valiant (1984), The Worst Witch (1998), Wolf Hall (2015) and several episodes of Doctor Who.

[55][79] The stone tiles on the roof were replaced by slate in 1972, a programme of repair was carried out on the Keep in 2007 and interior conservation work was undertaken in 2011 to address problems in Lady Bute's Bedroom, where damp had begun to damage the finishings.

[86] Its design combines the surviving elements of the medieval castle with 19th-century additions to produce a building which the historian Charles Kightly considered "the crowning glory of the Gothic Revival" in Britain.

[99] Almost equal in diameter, but of differing conical roof designs and heights, and topped with copper-gilt weather vanes, they combine to produce a romantic appearance,[3][91][100] which Matthew Williams described as bringing "a Wagnerian flavor to the Taff Valley".

The case appears to me to be thus: if a tower presented a good situation for military engines, it had a flat top; if the contrary, it had a high roof to guarantee the defenders from the rain and the lighter sorts of missiles.

[31] While the exterior of Castell Coch is relatively true to English 13th-century medieval design—albeit heavily influenced by the Gothic Revival movement—the inclusion of the conical roofs, which more closely resemble those of fortifications in France or Switzerland than of Britain, is historically inaccurate.

[31][87][102][103] Although he mounted a historical defence (see box), Burges chose the roofs mainly for architectural effect, arguing that they appeared "more picturesque", and to provide additional room for accommodation in the castle.

[96] Cantilevered galleries and wall-walks run around the inside of the courtyard with neat and orderly woodwork; the historian Peter Floud critiqued it as "perhaps too much like the backcloth for an historical pageant".

[56] The ceiling is supported by vaulted stone ribs modelled on Viollet-Le-Duc's work at Château de Coucy and the lower and upper halves of the room are divided by a minstrels' gallery.

[100][115] The ceiling's vaulting is carved with butterflies, reaching up to a golden sunburst at the apex of the room, while plumed birds fly up into a starry sky in the intervening sections.

[117] The architectural writer Andrew Lilwall-Smith considered the Drawing Room to be "Burges's pièce de résistance", encapsulating his "romantic vision of the Middle Ages".

[122] Crook suggested this provided some "spartan" relief before the culmination of the castle in Lady Bute's Bedroom but Floud considered the result "thin" and drab in comparison with the more richly decorated chambers.

[123] The bedroom is Moorish in style, a popular inspiration in mid-Victorian interior design, and echoes earlier work by Burges in the Arab Room at Cardiff Castle and in the chancel at St Mary's Church at Studley Royal in Yorkshire.

[125][126] Lilwall-Smith likened the chamber, with its "Moorish-looking dome, maroon-and-gold painted furniture and large, low bed decorated with glass crystal orbs", to a scene from the Arabian Nights.

[100] Peter Floud criticised the eclectic nature of this Moorish theme and contrasted it unfavourably with the more consistent style Burges applied to the Arab Room, suggesting that it gave the bedroom an overly theatrical, even pantomime-like, character.

[129][j] The Windlass Room includes murder holes, which Burges thought would have enabled medieval inhabitants of the castle to pour boiling water and oil on attackers.

[135] The area has unusual rock outcrops, which show the point where Devonian Old Red Sandstone and Carboniferous Limestone beds meet; the Castell Coch Quarry is in the vicinity.

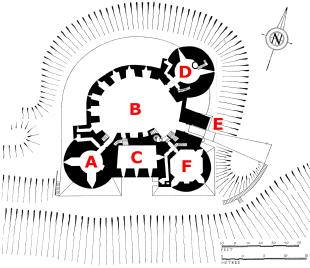

- A – Kitchen Tower

- B – Courtyard

- C – Hall Block

- D – Well Tower

- E – Gatehouse

- F – Keep