Castlerigg stone circle

In his study of the stone circles of Cumbria, archaeologist John Waterhouse commented that the site was "one of the most visually impressive prehistoric monuments in Britain.

[7][8] This plateau forms the raised centre of a natural amphitheatre created by the surrounding fells and from within the circle it is possible to see some of the highest peaks in Cumbria: Helvellyn, Skiddaw, Grasmoor and Blencathra.

[11] Two of Britain's earliest antiquarians, John Aubrey (1626–97) and William Camden (1551–1623), visited Cumbria with an interest in studying the area's megalithic monuments.

Both described Long Meg and Her Daughters, another large stone circle to the northeast of Penrith, and recounted local legend and folklore associated with this monument, but neither writers mentions a visit to Castlerigg or the area around Keswick.

Stukeley's observation of a second circle in the next field is a great revelation that places the stones at Castlerigg in a whole new light; that he fails to deliver a description demonstrates well the frustration felt by modern researchers when dealing with the works of antiquarians.

The apparently unspoilt and seemingly timeless landscape setting of Castlerigg stone circle provided inspiration for the poets, painters and writers of the 19th-century Romantic movement.

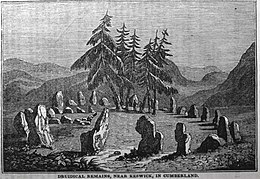

An early description of Castlerigg stone circle can be found in the 1843 book The Wonders of the World in Nature, Art and Mind, by Robert Sears.

The Druidical Circle, represented in the accompanying plate, is to be found on the summit of a bold and commanding eminence called Castle-Rigg, about a mile and a half on the old road, leading from Keswick, over the hills to Penrith,—a situation so wild, vast, and beautiful, that one cannot, perhaps, find better terms to convey an idea of it than by adopting the language of a celebrated female writer, (Mrs. Radclifle,) who, travelling over the same ground years ago, thus described the scene: "Whether our judgment," she says, " was influenced by the authority of a Druid's choice, or that the place itself commanded the opinion, we thought this situation the most severely grand of any hitherto passed.

There is, perhaps, not a single object in the scene that interrupts the solemn tone of feeling impressed by its general character of profound solitude, greatness, and awful wildness.

Castle-Rigg is the centre point of three valleys that dart immediately under it from the eye, and whose mountains form part of an amphitheatre, which is completed by those of Borrowdale on the west, and by the precipices of Skiddaw and Saddleback, close on the north.

The hue which pervades all these mountains is that of dark heath or rock; they are thrown into every form and direction that fancy would suggest, and are at that distance which allows all their grandeur to prevail.

Sears then continues his description: The one here represented is of the first, or simple class, and consists, at present, of about forty stones of different sizes, all, or most of them, of dark granite,— the highest about seven feet, several about four, and others considerably less; the few fir-trees in the centre are, of course, of very modern growth.

Near the bottom here, I found what I think to be a few small pieces of burned wood or charcoal, also some dark unctuous sort of earth, a sample of both I brought away.

What subsequently happened to the samples of 'burned wood or charcoal' and the 'dark unctuous sort of earth' is unknown, other than they are now likely to be lost or, if not, too contaminated to be worth modern scientific analysis.

The works of Burl strongly support the idea that any geometry within the circle, or astronomical alignments, are either purely coincidental or symbolic in nature.

[19] While neither Burl's nor Thom's works deal with Castlerigg exclusively, they do attempt to place all the stone circles of Britain in context to each other and to explain their purpose.

English Heritage subjected the scheduled area and the field to its immediate west to a geophysical survey in 1985 in order to improve our understanding of the stone circle and to provide a better interpretation for visitors.

In 2004, Margarita Díaz-Andreu, of the Department of Archaeology at Durham University, commissioned a survey of the stones at Castlerigg in response to claims that a "spiral carving" had been discovered there.

[17] Responsibility for the stone circle remains with English Heritage, the successor body to the Ministry of Works, whilst ownership of the site is retained by the National Trust.