Catalan number

Another alternative expression is which can be directly interpreted in terms of the cycle lemma; see below.

in the sense that the quotient of the n-th Catalan number and the expression on the right tends towards 1 as n approaches infinity.

This can be proved by using the asymptotic growth of the central binomial coefficients, by Stirling's approximation for

The odd Catalan numbers, Cn for n = 2k − 1, do not have last digit 5 if n + 1 has a base 5 representation containing 0, 1 and 2 only, except in the least significant place, which could also be a 3.

Since the 1D random walk is recurrent, the probability that the walker eventually arrives at -1 is

The book Enumerative Combinatorics: Volume 2 by combinatorialist Richard P. Stanley contains a set of exercises which describe 66 different interpretations of the Catalan numbers.

We first observe that all of the combinatorial problems listed above satisfy Segner's[9] recurrence relation For example, every Dyck word w of length ≥ 2 can be written in a unique way in the form with (possibly empty) Dyck words w1 and w2.

On the one hand, the recurrence relation uniquely determines the Catalan numbers; on the other hand, interpreting xc2 − c + 1 = 0 as a quadratic equation of c and using the quadratic formula, the generating function relation can be algebraically solved to yield two solution possibilities From the two possibilities, the second must be chosen because only the second gives The square root term can be expanded as a power series using the binomial series

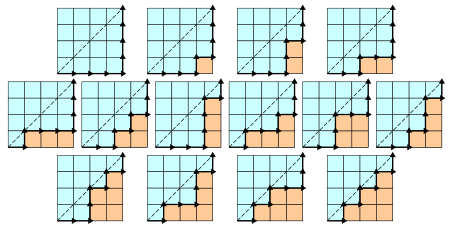

We count the number of paths which start and end on the diagonal of an n × n grid.

This bijective proof provides a natural explanation for the term n + 1 appearing in the denominator of the formula for Cn.

A generalized version of this proof can be found in a paper of Rukavicka Josef (2011).

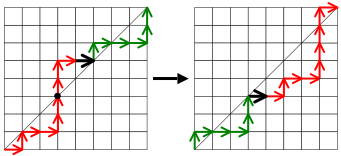

For example, in Figure 2, the edges above the diagonal are marked in red, so the exceedance of this path is 5.

In Figure 3, the black dot indicates the point where the path first crosses the diagonal.

The black edge is X, and we place the last lattice point of the red portion in the top-right corner, and the first lattice point of the green portion in the bottom-left corner, and place X accordingly, to make a new path, shown in the second diagram.

Alternatively, reverse the original algorithm to look for the first edge that passes below the diagonal.

In other words, we have split up the set of all monotonic paths into n + 1 equally sized classes, corresponding to the possible exceedances between 0 and n. Since there are

The columns to the right show the result of successive applications of the algorithm, with the exceedance decreasing one unit at a time.

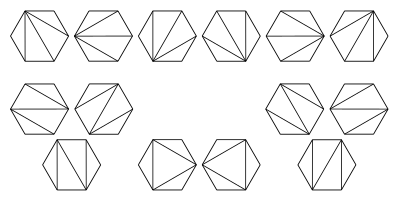

This proof uses the triangulation definition of Catalan numbers to establish a relation between Cn and Cn+1.

This proof is based on the Dyck words interpretation of the Catalan numbers, so

immediately gives the recursive definition Let b be a balanced string of length 2n, i.e. b contains an equal number of

, so Also, from the definitions, we have: Therefore, as this is true for all n, This proof is based on the Dyck words interpretation of the Catalan numbers and uses the cycle lemma of Dvoretzky and Motzkin.

Another feature unique to the Catalan–Hankel matrix is that the n × n submatrix starting at 2 has determinant n + 1. et cetera.

The Catalan sequence was described in 1751 by Leonhard Euler, who was interested in the number of different ways of dividing a polygon into triangles.

The sequence is named after Eugène Charles Catalan, who discovered the connection to parenthesized expressions during his exploration of the Towers of Hanoi puzzle.

The reflection counting trick (second proof) for Dyck words was found by Désiré André in 1887.

[14] In 1988, it came to light that the Catalan number sequence had been used in China by the Mongolian mathematician Mingantu by 1730.

[15][16] That is when he started to write his book Ge Yuan Mi Lu Jie Fa [The Quick Method for Obtaining the Precise Ratio of Division of a Circle], which was completed by his student Chen Jixin in 1774 but published sixty years later.

Peter J. Larcombe (1999) sketched some of the features of the work of Mingantu, including the stimulus of Pierre Jartoux, who brought three infinite series to China early in the 1700s.

For instance, Ming used the Catalan sequence to express series expansions of

The Catalan numbers can be interpreted as a special case of the Bertrand's ballot theorem.