Marian art in the Catholic Church

Images such as Our Lady of Guadalupe and the many artistic renditions of it as statues are not simply works of art but are a central element of the daily lives of the Mexican people.

[2] Both Hidalgo and Zapata flew Guadalupan flags and depictions of the Virgin of Guadalupe continue to remain a key unifying element in the Mexican nation.

Churches and specific works of art were commissioned to honor the saints and the Virgin Mary has always been seen as the most powerful intercessor among all saints—her depictions being the subject of veneration among Catholics worldwide.

[10][11] Paleotti's approach was implemented by his powerful contemporary Saint Charles Borromeo and his focus on "the transformation of Christian life through vision" and the "nonverbal rules of language" shaped the Catholic reinterpretations of the Virgin Mary in the 16th and 17th centuries and fostered and promoted Marian devotions such as the Rosary.

[17][18] As recently as 1992, the song The Lady Who Wears Blue and Gold was composed in California and then performed at St. Alphonsus Liguori Church in Rome, where the icon resides.

[27] As the tender joys of the Nativity were added to the agony of Crucifixion (as depicted in scenes such as Stabat Mater) a whole new range of approved religious emotions were ushered in via Marian art, with wide-ranging cultural impacts for centuries thereafter.

In the 13th century Caesarius of Heisterbach was also aware of this motif, which eventually led to the iconography of the Virgin of Mercy and an increased focused on the concept of Marian protection.

[34] Catholic Marian art has expressed a wide range of theological topics that relate to Mary, often in ways that are far from obvious, and whose meaning can only be recovered by detailed scholarly analysis.

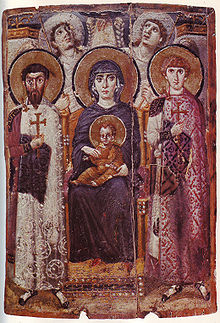

Mary's status as the Mother of God was not made clear in the Gospels and Pauline Epistles but the theological implications of this were defined and confirmed by the Council of Ephesus (431).

There was a great expansion of the cult of Mary after the Council of Ephesus in 431, when her status as Theotokos was confirmed; this had been a subject of some controversy until then, though mainly for reasons to do with arguments over the nature of Christ.

At this period the iconography of the Nativity was taking the form, centred on Mary, that it has retained up to the present day in Eastern Orthodoxy, and on which Western depictions remained based until the High Middle Ages.

The earliest surviving image in a Western illuminated manuscript of the Madonna and Child comes from the Book of Kells of about 800 and, though magnificently decorated in the style of Insular art, the drawing of the figures can only be described as rather crude compared to Byzantine work of the period.

[50] The depiction of the Madonna has roots in ancient pictorial and sculptural traditions that informed the earliest Christian communities throughout Europe, Northern Africa and the Middle East.

In the late Middle Ages, the Cretan school, under Venetian rule, was the source of great numbers of icons exported to the West, and the artists there could adapt their style to Western iconography when required.

In the Romanesque period free-standing statues, typically about half life-size, of the enthroned Madonna and Child were an original Western development, since monumental sculpture was forbidden by Orthodoxy.

The Golden Madonna of Essen of c. 980 is one of the earliest of these, made of gold applied to a wooden core, and still the subject of considerable local veneration, as is the 12th century Virgin of Montserrat in Catalonia, a more developed treatment.

Some images of the Madonna were paid for by lay organizations called confraternities, who met to sing praises of the Virgin in chapels found within the newly reconstructed, spacious churches that were sometimes dedicated to her.

An example is Our Lady of Aparecida in Brazil, whose shrine is surpassed in size only by Saint Peter's Basilica in Vatican City, and receives more pilgrims per year than any other Catholic Marian church in the world.

[52] Some noteworthy examples are: Images of, and devotions to, Madonnas such as Our Lady of San Juan de los Lagos have spread from Mexico to the United States.

Mary is shown as present at the Deposition of Christ and his Entombment; in the late Middle Ages the Pietà emerged in Germany as a separate subject, especially in sculpture.

[60] This dogma is often represented in Catholic art in terms of the annunciation to Mary by the Archangel Gabriel that she would conceive a child to be born the Son of God, and in Nativity scenes that include the figure of Salome.

[63] Frescos depicting this scene have appeared in Catholic Marian churches for centuries and it has been a topic addressed by many artists in multiple media, ranging from stained glass to mosaic, to relief, to sculpture to oil painting.

The figures of the Virgin Mary and the Archangel Gabriel, being emblematic of purity and grace, were favorite subjects of many painters such as Sandro Botticelli, Leonardo da Vinci, Caravaggio, Duccio and Murillo among others.

The definitive iconography for the Immaculate Conception, drawing on the emblem tradition, seems to have been established by the master and then father-in-law of Diego Velázquez, the painter and theorist Francisco Pacheco (1564–1644), to whom the Inquisition in Seville also contracted the approval of new images.

Although the Assumption was only officially declared a dogma by Pope Pius XII in his Apostolic Constitution Munificentissimus Deus in 1950, its roots in Catholic culture and art go back many centuries.

[77] He wrote: "On this day the sacred and life-filled ark of the living God, she who conceived her Creator in her womb, rests in the Temple of the Lord that is not made with hands.

[82] Although every year over five million pilgrims visit Lourdes and Guadalupe each, the volume of Catholic art to accompany this enthusiasm has been essentially restricted to popular images.

Yet images such as Our Lady of Guadalupe and the artistic renditions of it as statues are not simply works of art but are a central elements of the daily lives of the Mexican people.

The rich background representation of flowers or gardens found in Catholic art are not present in Orthodox depictions whose primary focus is the Theotokos, often with the Child Jesus.

And the presence of Sacramentals such as the Rosary and the Brown Scapular on the statues of Our Lady of Fatima emphasize a totally Catholic form of Marian art.