Catopsbaatar

Multituberculates would have been omnivorous; Catopsbaatar had powerful jaw muscles, and its incisors were well adapted for gnawing hard seeds, using a backwards chewing stroke.

Two-thirds of the collected specimens were multituberculates: an extinct order of mammals with rodent-like dentition, named for the numerous cusps (or tubercles) on their molars.

The specific name refers to the animal's similarity to the North American species Catopsalis joyneri, which Kielan-Jaworowska thought was a possible descendant.

[1][2][3][4] Kielan-Jaworowska and American palaeontologist Robert E. Sloan considered the genus Djadochtatherium a junior synonym of Catopsalis, and created the new combination C. catopsaloides in 1979.

[5] American palaeontologists Nancy B. Simmons and Miao Desui conducted a 1986 cladistic analysis which indicated that Catopsalis was a paraphyletic taxon (an unnatural grouping of species), and C. catopsaloides required its own generic name.

[8][7] The word baatar is used as a suffix in the names of many multituberculate genera, and alludes to the Mongolian capital Ulaanbaatar, which itself means "red hero".

The specimen has rather complete fore- and hind limbs, which were unknown for the genus until then and which are generally rarely preserved in multituberculates.

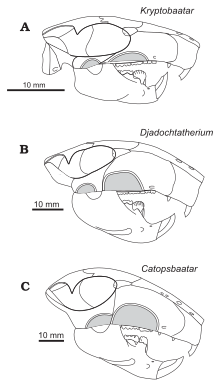

It was shorter along the midline than at the sides, because the nuchal crest at the back of the head curved inwards at the middle, creating an indention at the hind margin of the skull when viewed from above.

The premaxilla consisted of parts of the face and the palate; djadochtatheriids had a premaxillary ridge on the boundary between the two (visible when viewing the skull from below).

The nasal bone—which formed the upper part of the snout—was relatively wide (becoming wider towards the back), and its front was covered with irregularly spaced vascular foramina.

One of the most characteristic features of the face of Catopsbaatar was the very large anterior zygomatic ridge on the sides of the upper jaw (a site for jaw-muscle attachment).

The lower part of the suture between the maxilla and the squamosal bone extended along the hind border of the anterior zygomatic ridge.

One lumbar vertebra (the fifth or sixth, from between the rib cage and the pelvis) had a spinous process which was stout in side view and long when seen from above.

The clavicle was slightly less curved than that of Kryptobaatar (resembling a bent rod which widened at each end), and measured about 24.8 mm (0.98 in).

[13] Unlike most other multituberculates and other mammals, the calcaneus bone at the back of the foot had a short tuber calcanei (like some tree kangaroos), with an expanded, anvil-shaped proximal process strongly bent downwards and to the side.

Catopsbaatar had an os calcaris bone on the inner side of its ankle, a feature also seen in modern male monotremes (the platypus and the echidna) and other Mesozoic mammals.

Because there would be little space for the passage of an egg (egg-laying monotremes have wide ischial arches), Kielan-Jaworowska suggested in 1979 that multituberculates were viviparous (gave live birth) and that the newborns were extremely small—similar to those of marsupials.

[4][18] Although multituberculates were thought to have been carnivores or herbivores, since American palaeontologist William A. Clemens and Kielan-Jaworowska suggested modern rat kangaroos as analogues for the group in 1979 they have been considered omnivores (feeding on both plants and animals).

[4] Uniquely among mammals, multituberculates employed a backward chewing stroke which resulted in the masticatory muscles—the muscles which move the mandible—being inserted more to the front than in other groups (including rodents).

Their powerful incisors, with limited bands of enamel, would have been well adapted to gnawing and to cutting hard seeds (similar to rodents).

Since it was larger than some other multituberculates, Catopsbaatar would have to open its mouth only 25 degrees to crush hard seeds 12–14 mm (0.47–0.55 in) in diameter; a 40-degree gape would have caused dislocation.

[12] According to Gambaryan and Kielan-Jaworowska, the adaptation for crushing hard seeds sometimes—as in Catopsbaatar—opposed the benefit of a low condylar process (which discourages mandibular dislocation).

The anterior and intermediate zygomatic ridges of the skull were the origin of the superficial masseter muscle, which facilitates chewing.

The masticatory muscles of multituberculates independently evolved features shared with rodents and small herbivorous marsupials.

Kielan-Jaworowska and Hurum supported the latter theory in 2006 based on the presence of hind-leg spurs, a feature they considered present only in sprawling mammals.

Kielan-Jaworowska and Hurum depicted Catopsbaatar with plantigrade, sprawling legs, with mobile spurs which pointed inward when preparing for attack.

[3][21][22] The rock facies of the Red Beds of Hermiin Tsav area consist of orange-coloured, thick-bedded sandstone, with a thin interbedding of light-coloured silt stones and claystones.

[23][3] The rock facies of the Barun Goyot Formation are considered to be the result of an arid or semi-arid environment, with aeolian (deposited by wind) beds.

[24][22] Other known mammals from the Red Beds of Hermiin Tsav include the multituberculates Nemegtbaatar, Chulsanbaatar and Nessovbaatar, and the therians Deltatheridium, Asioryctes, and Barunlestes.

Reptiles include the turtle Mongolemys, the lizards Gobinatus, Tchingisaurus, Prodenteia, Gladidenagama and Phrynosomimus, and an indeterminate crocodile.